Published on May 25, 2013

Umberto Nobile had already been to the North Pole once by airship, having piloted the Norge, a semi-rigid dirigible of his own design, on a journey from Spitsbergen, Norway, in 1926. That expedition had carried the famous Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen on board and had been funded largely by the American, Lincoln Ellsworth. While entirely successful, Amundsen viewed Nobile as a “mere pilot”, while Nobile thought Amundsen to be something of a passenger, even if a famous one. The friction between the two men flared in the wake of the Norge’s voyage. And so, Umberto Nobile, having been made a General in the Italian military and invited into the ranks of Mussolini’s fascist ruling party, set out to undertake another, more scientific voyage. This time, he would design an even better dirigible and, to avoid any confusion as to who was in charge, he brought an all-Italian crew and christened the new airship Italia.

Nobile’s second voyage, however, would end in disaster, costing the lives of more than a third of his crew. As well, Nobile’s rival, Roald Amundsen, would bury the hatchet, hire a plane, and take off to join the search for survivors. He and his plane, along with the others on board, disappeared into the cold Arctic seas, compounding the disaster.

The Flight of the Italia

Prior to the Italia’s journey from Spitsbergen to the North Pole, an earlier flight had taken off on May 15 to search any lands between Spitsbergen and the Russian island of Severnaya Zemlya. After 69 hours and 2,400 miles had passed, the airship had returned successfully to Spitsbergen. No lands had been sighted. Feeling confident, at 4:28 am on May 23, 1928, the Italia and its crew set out once more from Spitsbergen’s King’s Bay. Sixteen men were on board.

Nobile’s flight crew consisted of Nobile himself, plus two navigators, Commander Adalberto Mariano and Commander Filippo Zappi. Two additional officers were also brought in, Alfredo Viglieri and Felice Trojani, as well as two radiomen, Ettore Pedretti and Guiseppe Biagi. Under Ettore Arduino, who served as chief engineer, four mechanics and riggers were selected including Attilo Caratti, Vincenzo Pomella, Calisto Ciocca and Renato Alessandrini.

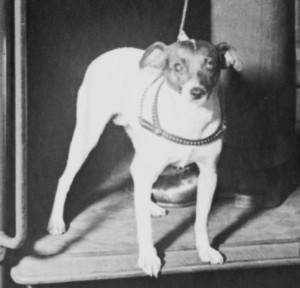

Additionally, a scientific crew was brought along, which included a Swedish meteorologist named Finn Malmgren from the University of Uppsala; a Czech named Francis Behounek, PhD; and a physics PhD from Milan named Aldo Pontremoli. Two journalists, Francesco Tomaselli and Ugo Lago, were brought along to record the mission’s success. Nobile also brought his dog, a fox terrier named Titina, who had accompanied him on the Norge as well in 1926.

To support the mission, the aging merchant ship, Citta di Milano, was assigned under Guiseppe Romagna. In the event that rescue operations were needed, eight elite Alpini mountain troops were billeted on board. Nobile’s request for two seaplanes to stand ready at Spitsbergen was, however, denied. The mission did not enjoy full support from Italy’s Air Undersecretary, the famed international pilot Balbo, but it did carry the blessing of Pope Pius XI, who granted a special audience to the crew and then sent a cross along to plant on the North Pole.

After departing for the North Pole, the Italia headed north through fog but emerged into crystal clear air that allowed the crew to sight Greenland. They enjoyed blue skies and visibility estimated at 60 miles — yet in every direction was unrelenting ice pack. A strong tail wind pressed them forward ahead of schedule. On May 24, at 12:20 am, the Italia reached the North Pole. High winds, however, prevented the airship from landing. To honor the wishes of the Pope, the flight crew tossed the cross out into the air and watched as it fell onto the ice below. To celebrate, they played a phonograph with the tune “Bells of St. Giusto”. As well, they played the Fascist hymn “Giovinezza”. As well, they dropped the Italian flag and a marker in honor of the city of Milan.

Elated, they circled the pole while Nobile consulted with the Swedish meteorologist Finn Malmgren. He advised that the best option was to turn back toward Spitsbergen rather than continuing to Canada or Alaska, flying to Greenland, or turning toward the Russian coast. Malmgren’s advice, however, had put them into the teeth of the very wind that had carried them north. Now, instead of averaging a ground of 69 mph, they were clawing their way south at a speed of just 25 mph. Soon, they entered a fog, then ominously, heavy snow began to pelt the airship.

Crisis on the Italia

Ice soon formed on the airship’s top and sides. The propellers were also picking up ice which flew off like bullets into its sides. As the airship descended in the storm, it was soon at only 750 feet of altitude. The ice build up then forced the elevator to jam into a downward angle. The Italia nose-dived toward the ice. Thinking fast, Nobile ordered the airship’s three Maybach engines stopped.

At 250 feet, the dive ended. For a short while, they were blown along in the wind, but then the airship began to rise. Nobile had averted a crash and felt justified in letting the airship continue up above the clouds into the sun, hoping to melt the ice and find safety. The airship continued to rise until it achieved an altitude of 2,700 feet. Above the clouds, the two navigators took a sun shot to log their position — they were just 180 miles from King’s Bay. Nobile had intended to arrest the climb at that point, but the airship continued upward, reaching 3,300 feet of altitude. This resulted in the hydrogen pressure valves opening to vent off the stresses on the airbags from the expanding gases. Finally, the Italia descended back downward into the cloud to continue to press against the wind toward Spitsbergen.

Leveling off at 300 feet, the Italia made headway against the storm, even if it was slow progress. The airship was straining against the wind. Suddenly, the crew called out that the stern of the Italia was inexplicably heavy. It began to drop, forcing the Italia to sag toward the ice. It was a very slow descent, just two foot a minute, but it seemed that Nobile’s crew could not arrest the descent. Soon the descent rate was accelerating. Nobile realized that the Italia would crash. He ordered that the engines be shut down so as to result in a vertical impact, rather than a forward, high speed collision with the ice. His best guess as to the cause was that one of the valves to bleed excess pressure had frozen open, perhaps having iced up.

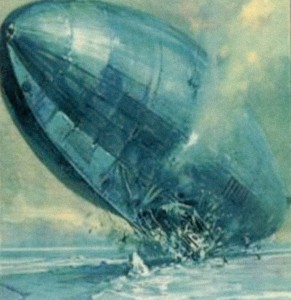

The Crash

At 10:33 am on May 25 — today in aviation history — the Italia struck the ice. The force of the impact sheered off most of the control cab, casting ten men out onto the ice pack, injuring three and killing one. Suddenly lighter, the rest of the dirigible was carried back upward by the gas bags — six men were still on board. One, the chief engineer Ettore Arduino, upon seeing the commander and others falling out to be stranded on the ice pack below, chose to not attempt a jump but rather threw out armloads of supplies to the men. Had he not done so, the men would have likely perished. Yet Arduino and five others — Aldo Pontremoli, Ugo Lago, Calisto Ciocca, Attilio Caratti, and Renato Alessandrini — flew helplessly off in the stricken airship. As the Italia drifted off in the high winds and disappeared, the survivors on the ice pack considered their situation — Nobile’s arm and leg were broken. The Swedish meteorologist Malmgren had a hurt shoulder, while another had a broken leg. Vincenzo Pomella had died when falling to the ice.

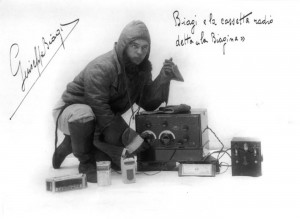

A short while later, the survivors saw a column of smoke on the horizon to the north — perhaps it was a fire from the crash of the rest of the dirigible. None of the six men who had ridden that portion back aloft were ever seen again. For Nobile and his crew, the harsh reality of surviving the Arctic was now upon them. He considered his options as the men gathered what supplies could be found amidst the wreckage of the control cab. The surviving radiomen called out one bit of good news — he had located the airship’s emergency radio.

With that in hand, radioman Guiseppe Biagi began sending out a morse code signal — “SOS NOBILE”. Over time, he would add a frequency for response, the 32 meter wavelength which they would monitor — thus, the message became, “SOS NOBILE IDO 32”. Soon thereafter, they located a bag containing a 9 square meter sized silken tent that used layers for insulation, with a 2 meter tent pole. Inside were also some provisions and a sleeping bag.

Nobile realized that perhaps they might survive after all. What he didn’t know was that aboard their escorting merchant ship, the Citta di Milano, the radio operators weren’t bothering to monitor the frequencies for any emergency message. It was the first of a long series of errors that would bring yet more death to the survivors in the coming days….