Published on May 24, 2013

Mr. Tsoe. K. Wong, a Chinese living in England, saw an opportunity to design and build a biplane which, once tested and proven, could be brought to China and marketed to the government and vast population of people there. After some months of hard work in the design during 1912 at Shoreham Aerodrome in Sussex, he began to build what he called the “Tong-Mei”, which translates from Chinese to “Dragonfly”. Influenced deeply by the work of many English flyers and builders, his plane was soon taking shape, its skeletal structure still devoid of fabric, its engine yet to be mounted. In the design, despite its English roots, the forms and traditions of the Far East were clearly evident. There was promise enough there that the biplane was worthy of review in Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club in their late May 1913 issue — 100 years ago today in aviation history. The writers noted dryly:

“It is encouraging to note that Mr. Wong has made England the base for his preliminary organisation. He is arranging to take back several English pilots and mechanics. FLIGHT readers will no doubt wish him every success in his enterprise. A two-seater machine of the same type is now in course of construction, and will, as soon as it is completed and tested, be dispatched to China.”

It was an effort that would prove to be a bit too hopeful.

Details of the Tong-Mei Biplane

By mid-1913, the engine was mounted — a 40 hp ABC four-cylinder inline — the plane was nearing readiness for its first flights at the Shoreham Aerodrome in Sussex over the summer. Mr. Wong also began his own piloting lessons in the second week of July 1913 at the Ducrocq and Lawford School. On August 15, 1913, certificate #593 would be awarded to “Gordon Tsoe Kwong Wong”, noted as a “Chinese subject”, after having tested at the Bristol School on a Bristol Biplane. With that, Mr. Wong was ready to fly his own design!

He found the Tong-Mei biplane flew reasonably well. It was light, weighing just 504 pounds (without engine, pilot or fuel), giving it good handling. The engine and fuel tank would allow a 3.5 hour endurance. With several test flights successfully under his belt, Mr. Wong found two others who shared the dual interests of aviation and the Far East. In December 1913, two Englishmen, W. F. Skene (brother of another pilot at the Brooklands Bristol School) and Eardley H. Lawford (another pilot who trained with Mr. Wong), as well as Mr. Wong established their company, known as T. K. Wong Ltd., which was headquartered at 17, Ironmonger Lane, London EC. In the public announcement, it was noted that the company’s initial capital was £2,000, which was issued in £1 shares. Proudly, the company declared themselves to be, “Manufacturers of and dealers in aeroplanes, balloons, airships, &c.”

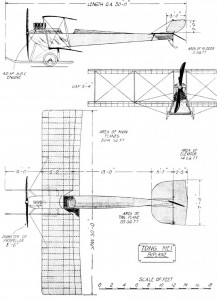

Additional flight testing followed at Shoreham in 1914. It was realized that if it were to be properly demonstrated, the single-place configuration would have to be altered. A second seat was installed and the original ABC 40 hp water-cooled engine was replaced with a larger, more powerful 100 hp Anzani radial engine. The main fuselage and wings were spruce with fabric covering, while the fuselage ahead of the cockpit was made of a mix of flat sheets of aluminum on the sides and rounded sheets on the top and bottom. The wings were 30 feet in span and staggered, nearly of equal size with a trailing edge sweep back to provide greater roll authority — control was via wing warping.

Throughout the design, efforts were made to simplify the structure for repair, using whatever local materials could be found in China and the Far East. The landing gear were simple and structurally sound. The wing struts were all identical. The wing ribs were six-ply laminated spruce, designed to be rugged and hold their shape in all weather, humidity and aerodynamic stress. Even the elevator was built as a single plane with two control attachment points, adding safety in the event that one of the cables snapped. It was a revolutionary design in terms of the environment and Far East market conditions.

The End of the Tong-Mei

By mid-1914, the Tong-Mei was packed and shipped to Kuala Lumpur, Selangor, in what was then known as the Federated Malay States. At the Kuala Lumpur, the huge 8 and 1/2 foot propeller was mounted and the wings lifted on. The vision was simple — the plane would be demonstrated at the polo grounds (some incorrectly claimed that the flights were at the nearby horse racetrack). The polo ground served as a makeshift airfield. Mr. Wong hoped that once popularized, his Tong-Mei biplane would open the market, first within the Federated Malay States and later across China and the Far East. In the early morning of Saturday, July 11, 1914, before any onlookers arrived, several flights of the Tong-Mei were made — each ending perfectly. Pleased with the results, Mr. Wong prepared for the afternoon demonstration as crowds assembled. He would pilot the machine himself.

Seeing the interest swelling, Mr. Wong felt that his two years of efforts were finally about to come to fruition. Instead, everything went horribly wrong. Rather than dazzling the public and government, the Tong-Mei crashed — it was just a bad landing after a first 10 mile flight at an altitude of 1,000 feet that had been meant to introduce the aeroplane to the crowd and surrounding area. On landing, he overran the limits of the field, quite nearly coming to a stop, but hitting the fence at a speed of about 5 mph. The prop was shattered and the skids were damaged. He took his time rebuilding it.

On Saturday, July 18, he again flew, this time for ten minutes, having moved to the racecourse instead, which promised a longer field for landings. Once again, disaster struck as he landed and tore a tire. Repairs were completed within the day and on Sunday afternoon of July 19, he took off again. He flew 20 minutes perfectly but when nearing Ampeng, the Anzani engine suddenly stopped. As he glided down, he apparently stalled the plane, which fell steeply and crashed into the ground — at the time, onlookers surmised that he had “hit an air pocket and fell”. Thankfully, Mr. Wong was uninjured, though the biplane was smashed.

Aftermath

The Tong-Mei had neither impressed nor gained the interest of any who had attended the first flight. Though the one photo known of the post-crash aeroplane seems to suggest that it could have been rebuilt, something must have happened as it was beyond repair. The best guess — if one is allowed to do that based on the scant evidence of a report at the time that stated that he hoped to save the engine, thus implying some question on the matter — is that the 100 hp Anzani was indeed damaged badly in the crash. No replacement engine was available which would have doomed the project entirely.

Those who observed the machine decided that aviation was still too nascent to be yet of serious interest. Even if another aviator had earlier tried to gain the interest of the Malay States in aviation, a Dutch pilot named Kuller, who flew an Antoinette in several demonstrations, it would seem that China and much of the rest of the Far East (except Australia and Japan) would be doomed to a slower start in the field of aviation than Europe. It was a terrible legacy, one that could have been reversed if not for the untimely failure of Mr. Wong’s Tong-Mei biplane.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Eardley H. Lawford enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps and entered the war in 1914 initially as a mechanic with 5 Squadron. By 1916, the RFC had figured out that Lawford, who had been nicknamed “Bill” as it was easier to say than Eardley, was reassigned as a pilot with 7 Squadron and deployed to France where he flew the B.E.2c over the Somme battlefield doing reconnaissance, observation, artillery spotting and bombing missions. After the war, he served as the very first pilot with Aircraft Transport and Travel Ltd. (known as AT&T, and one of the companies that became British Airways). On August 25, 1919, with a morning flight, he inaugurated the first scheduled air service between London and Paris, flying a de Havilland D.H.4A (G-EAJC) from Hounslow Heath to Paris-Le Bourget.

I came across your article, while doing research on early Malayan aviation history. In your article you mentioned that “the plane would be demonstrated at the polo grounds (some incorrectly claimed that the flights were at the nearby horse racetrack). The polo ground served as a makeshift airfield.” I went thru the Straits Times archive and found one article dated 20 July 1914, referring the landing site as the race course while another article dated the next day referring the landing site as the polo ground. (see my blog) I also found an article dated 27 March 1912 confirming that a polo match between Selangor and Singapore was played at the Kuala Lumpur race course. I can’t find anything in the archive that the Selangor Polo Club has its owned polo ground in the early 1900. I believe that in the newspaper reports, the word “polo ground” and “race course” referred to the same place i.e. Kuala Lumpur race course. One more point to add, the present (Royal) Selangor Polo Club ground near the old Kuala Lumpur race course(where the plane landed) only came into existence in 1960.

I am researching early Chinese aviation for an architectural project to be placed in China. I would appreciate any other info for very early aviation in China.