Published on June 19, 2013

By Thomas C. Van Hare

Vice Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo had gathered his forces in secret, creating the largest naval fleet Japan had yet assembled in the war. Two years after the 1942 losses in the Battle of Midway, Japan was ready again to go on the offensive. A rapid build-up of naval forces gave the Japanese confidence that this time they would issue a knock-out blow against the Americans. Three fleets were combined to bring nine aircraft carriers together to sail into battle. Newly trained pilots and the latest models of Japanese fighters, bombers and torpedo planes, were prepared. If Vice Admiral Ozawa could lure the Americans into an open engagement, with such a strong fleet in his hands, he hoped to annihilate the US Navy and regain dominance in the Pacific. His confidence was further bolstered by the extensive modernization of his fleet’s aircraft.

Then, the surprise news came that the American Navy had begun the assault on Saipan on June 16, 1944. It seemed clear that the American fleet was tied up preparing for attacks on Guam and Tinian. In Vice Admiral Ozawa’s view, the Marianas were strategically critical and yet also presented the opportunity to trap the unwitting Americans in the grip of his newly assembled, powerful fleet. He sailed out in a decisive move that he hoped would catch the Americans by surprise as they might remain intent on the island invasions, unaware of the approach of the most powerful naval force that Japan had ever sailed. Outnumbered, he considered that the US Navy would be overwhelmed and defeated in a single fatal blow.

It would be a massacre — at least that was Ozawa’s plan. So began the audacious and powerful attack code-named Operation A-Go. It was a battle that began 69 years ago today in aviation history, on June 19, 1944, and, like Pearl Harbor, it too would be viewed as “a date which will live in infamy”, though for the opposite reasons.

Composition of the Japanese Fleet

The 1st Mobile Fleet was the core of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s effort for Operation A-Go and was held under the direct command of Vice Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo himself. This consisted of three forces, each with three aircraft carriers, two or more battleships and cruisers and an array of destroyers and support ships. The Mobile Force Vanguard, also known as “C Force”, under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita, had the light aircraft carriers Chitose, Chiyoda and Zuiho as well as the two super battleships Yamato and Musashi and the battleships, Kongo and Huruna. “A Force”, under the personal control of Ozawa, brought the fleet carriers Taiho, Shokaku and Zuikaku as well as two cruisers, Haguro and Myoko to the battle. “B Force”, under Rear Admiral Takaji Joshima, fielded the fleet carriers Junyo, Hiyo and Ryuho as well as the battleship Nagato and the cruiser Mogami. In each force, multiple cruisers, destroyers and support ships were deployed.

In summary, the Japanese naval forces included nine aircraft carriers with 435 aircraft, the full range of battleships and cruisers and dozens of destroyers as well as the full complement of support ships like tankers, oilers and logistics vessels. Remembering the success of the submarine attack on USS Yorktown at Midway, the IJN also fielded no less than 24 submarines to help engage the American fleet. In the carrier-based air arm, the IJN aircraft were the newer, upgraded A6M5 Zero; the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei “Comet” (aka “Judy”) dive bomber, which was the replacement for the older “Val”; and the Nakajima B6N Tenzan “Heavenly Mountain” (aka “Jill”) torpedo bomber, which was the replacement for the outdated B5N “Kate”. At Guam and among surrounding bases, the Japanese assembled a formidable land-based air force of 1,200 aircraft, almost all of modernized types.

The American Fleet

On the American side, the landings on Saipan were supported by the US Navy’s 5th Fleet under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance. This included Task Force 58 under Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, as well as three battleship divisions (7, 8 and 9) and two submarine task forces. In all, the Americans fielded an astonishing 15 aircraft carriers including USS Hornet, USS Yorktown, and two light carriers, USS Belleau Wood and USS Bataan in TF 58.1 under Rear Admiral Jocko Clark; USS Bunker Hill, USS Wasp, and two light carries, USS Cabot and USS Monterey in TF 58.2 under Rear Admiral Alfred Montgomery; USS Enterprise and USS Lexington, as well as two light carriers, USS San Jacinto and USS Princeton in TF 58.3 under Rear Admiral John Reeves; and finally USS Essex and two light carriers, USS Langley and USS Cowpens in TF 58.4 under Rear Admiral William Harrill.

Assigned to the 15 aircraft carriers were 891 aircraft, mainly Grumman F6F Hellcats, TBM/TBF Avengers and SBD Dauntlesses and SB2C Helldivers. The light carriers were still equipped with the older Grumman F4F Wildcats. However, the fleet carriers fielded the new F6F Hellcats, qualitatively superior to the best the Japanese had and these formed the mainstay of the American carriers’ fighter forces. The pilots were well-trained, even if mostly recent graduates from the extensive air training efforts underway throughout the USA, though primarily in Florida, Michigan and California. The men flying the planes may not have been highly experienced, but they were the best trained, most organized and coordinated air combat units in the entire Pacific theater. The lessons of air combat learned at Guadalcanal, in the Solomons, at Midway and elsewhere were carefully trained to the American pilots. As well, American ingenuity had developed a range of new technologies, including the experimental Combat Information Center concept — giving the US Navy the first ever coordinated view of the battle space.

The Largest Aircraft Carrier Battle in History

On June 17, while chasing a Japanese tanker, the US Navy fleet submarine USs Cavalla (SS-244), under the command of Lt. Commander Kossler, was led to and spotted the approaching Japanese fleet not far from the Philippines. He broke off the attack and instead began shadowing the Japanese fleet and reporting on its location. His transmissions confirmed what the Americans already knew from having broken the Japanese code systems earlier in the war — that the Japanese were coming in force. Quickly, a small force of submarines was assembled to harass and follow the Japanese fleet. Thus, USS Harder (SS-257), USS Bonefish (SS-223) and USS Puffer (SS-268) began a steady harassing action as well as regular reporting on the Japanese position. What was coming would not be an engagement like Midway where the Americans and Japanese blindly searched for one another in the early phases — the two great fleets would engage in full knowledge of their relative positions, with the Japanese knowing the American fleet was near Saipan and the Americans watching the Japanese fleet’s every move.

On June 18, while still 600 miles from the Marianas, the Japanese reconnaissance planes confirmed the location of the American fleet, determining its exact disposition. With their longer range patrol planes, the Japanese considered that they had a considerable advantage going into the battle — with the approaching night, however, the Japanese commanders recognized that the Americans could well reposition their ships under the cover of darkness. In the meantime, American planes flying searches could not yet detect the Japanese, though ongoing submarine reports gave confidence in the Japanese general location and approach.

Overnight, both fleets turned to the south, the Japanese hoping to get closer to their land-based air power and possibly lure the American ships into a closer engagement with their superior numbers of land-based aircraft. The Americans sought to gain advantage by repositioning during the cover of night to flank a more direct approach expected by the Japanese. By using their newly developed radar systems that were installed on their patrol planes, the US Navy pilots were able to fan out 500 miles from Task Force 58 in the direction from which the Japanese were known to be approaching. However, the Japanese remained undetected, remaining just outside of range. At 04:45 am, to ensure that there would be no surprises, the Japanese launched three waves of patrol planes. They remembered how they had suffered badly from surprise at Midway. Less than three hours later, another patrol plane — one of 50 launched from Guam — reported in with a confirmed sighting of Task Force 58. The American repositioning to the south had been revealed.

The Battle is Joined

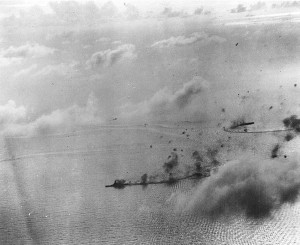

As dawn broke on June 19, the two sides were not quite in range of each other’s carrier-borne aircraft. In the meantime, Japanese land-based aircraft were called into the attack, launching in a first move against the Americans, though it would prove ineffective. This initial effort would mark the beginning of a two day battle that would become the largest naval conflict in the history of World War II. Incredibly, what followed is often glossed over by those who study the Pacific War — in short, though most can relate details of Pearl Harbor and the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, few can describe the most sweeping, largest and decisive engagement of the entire Pacific war. This was the naval engagement that would come to be known as the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

And though not quite as Vice Admiral Ozawa had predicted, it would be a massacre indeed.