Published on June 5, 2013

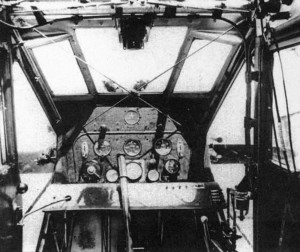

When Al and Fred Key took off in their Curtiss Robin “Ole Miss” on June 4, 1935, they were supported by a committed, if small team of other aviators and ground crew. Their flight hoped to break the endurance record of 23 days in the air without landing. It was challenging, to be sure, but with the community behind them, the two brothers felt confident. With the airborne VHF radio mounted in the plane — a pioneering radio design by Ben Woodruff that featured an antenna that was reeled out 100 feet behind the plane — the two brothers could stay in touch with the ground crew on a continuous basis, relaying requests for food, drinks, parts (if needed), fuel and oil. Woodruff even set up a loudspeaker at the ground VHF radio room so that visitors to the airport could listen on the flight communications. However, there was no other radio than those two — one in the airplane and one on the ground.

Without a radio, the support aircraft that was to undertake the refueling could not be contacted once it was airborne. For that, another workaround was developed — one that would have to stand the test of repeated join-ups — over 100 in all. Incredibly, it would involve visual signals from the ground so that both planes could easily find one another. With perhaps a full month of constant flying ahead of them, the men wondered whether those signals would work in bad weather. It was the first of many such issues that had to be dealt with as the flight began.

Refueling and Resupply Methods

The method of managing the join-ups was innovative. Hourly, the plane completed a set orbit over Meridian, Mississippi, passing a large field. There, on the ground, Ed McKellar, who was attending the long flight on behalf of the National Aeronautics Association (thereby validating the record setting flight), would stand in the middle of a wide field, wearing a white shirt and holding a signal flag. When the refueling plane was aloft, if it was having trouble finding the other aircraft, he would spot it against the sky and, using the flag, signal the direction to fly. Both planes, by prearranged agreement over the VHF radio before take off, would plan to fly at the same altitude. Typically, this was at 3,000 feet.

Aerial refueling was never done at the last moment when the tanks were nearing empty. Thus, if something went wrong, they would be able to try a second time. The refueling pilot, James Keeton, would join with the Key brothers while both planes orbited. Keeton would take up an orbit inside the wider orbit of the other aircraft. This way, the distance between them would quickly close into a perfect join-up every time. Once positioned in close formation behind and beneath the refueling plane, the two Key brothers would simply wait while Bill Ward lowered the refueling hose and connector to “Ole Miss”. Once the fuel line was attached, the fuel would flow automatically.

They found that the best distance to fly apart, minimizing turbulence against the fuel line, was between 10 and 15 feet apart. If for any reason the hose pulled off, which it often did, the unique connecter served as a mechanical cut-off valve, ensuring that all fuel flow stopped instantly. Between four and five aerial refueling operations were made per day, during which food and drink was also passed to the plane — dutifully packed by the pilots’ wives on the ground.

Dealing with Fog

One problem encountered was that fog sometimes shrouded the airport when dawn broke, at which time the first refueling operation of the day was needed. The night before, the tanks would be topped off and by morning they would be about 2/3 empty. This gave time to wait for the fog to lift, but sometimes the fog remained stubborn. In an era without modern radio navigational aids or equipment on the planes for flights into instrument conditions, the refueling plane would take off anyway, climb through the fog and emerge on top to locate the Key brothers. At the end of the refueling operation, however, the refueling plane would have to land again — without instruments, into the fog, to find the runway.

To do this, the pilots simply scanned the top of the fog layer from above, looking for wisps of the black coal smoke that many in Meridian burned to heat their homes. They would carefully assess the rough map of black smoke to discern the layout of the town and then, based on that, they would descend into the fog at the point where they knew the airfield had to be. Feeling their way down in the fog, they found the airport and landed time after time flawlessly.

Lowering Supplies

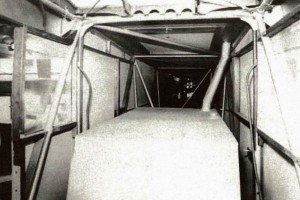

The first attempts to lower food to the Key brothers was a disaster. The food was packed into a square container and attached to a rope. In the back of Keeton’s Curtiss Robin, Bill Ward lowered the container, only to find that its square sides caused it to lash about, twisting and bobbing back and forth on the line. When the lower plane neared the container, the turbulence worsened and it slammed into the nose of the airplane and windshield several times. Finally, the Key brothers backed off and flew up alongside to shake their heads with a “no”.

Keeton returned to the ground and another container was acquired. This next time, they would try a rounded cylinder originally used for ice cream. With a little extra weight added in the bottom of the can, they took off and tried again. When that cylindrical container was lowered, its more aerodynamic shape kept it stable enough for the package to be delivered. Had the second container not worked out, they Key brothers would have had to abort the record attempt. Still, the new container was small and after each refueling, multiple transfers were required, laboriously lowering and raising the ice cream can again and again to the two waiting pilots.

The most amazing circumstance emerged when on June 22, Al Key radioed that he had a toothache. The condition grew worse and worse and, with a dentist brought in to consult over the VHF radio, they realized it was a abscess. The following day, with the dentist, Dr. Rush on hand, supplies were sent up to the plane for Fred to use in operating on Al in mid-flight. That evening, as they prepared for the operation — without any painkillers and with the plane trimmed for straight flight — the abscess surfaced and Fred was able to lance it using just iodine, cotton and needle. The pain subsided and the pair continued their flight.

Finally, at a critical point near the end of the operation, Bill Ward was unable to fly and handle the aerial refueling. A local airport porter, an African American named Germany Johnson, volunteered to do the refueling instead — he performed flawlessly. With that, the Key brothers were able to continue with their record setting flight.

Success and the Future

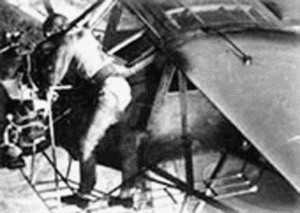

Day after day, despite bad weather, fog, scheduling issues when maintenance was required on one or another plane, the flight continued. Airborne oil changes worked exactly as planned, with Fred Key standing on the catwalk at the nose of the plane, draining and filling oil as the engine ran. After just a little more than three weeks, they surpassed the Chicago record. With thousands of well-wishers lining the airfield, the Key brothers made a low flyby to wave at the crowds, but then simply climbed back up and continued their orbiting. By then, the steadily building press coverage of their effort had gained statewide attention — then nationwide attention as well. That night, the airfield was renamed Key Field in honor of the two pilots. After that, with every passing day, news reports of their progress expanded. While they could have landed at any time once the record was attained, they remained aloft in order to publicize their key goal, to help gain public support for Meridian Municipal Airport and thereby keep it from being forced to close down.

On June 29, the flight almost came to a disastrous end. During a refueling, one of the metal oil cans came in contact with some exposed electrical wiring in the plane, which caused a short circuit. A fire broke out and the plane, newly filled to capacity with gasoline, appeared ready to go down in flames. Al was flying and he cut the engine as Fred grabbed a fire extinguisher and blasted the flames — luckily, the fire went out, leaving the plane filled with smoke. Al pulled out of the dive, restarting the engine, less than 100 feet from the ground.

Finally, on July 1, 1935, after a storm had damaged the stabilizer, the Key brothers called an end to their flight and landed “Ole Miss” at the airport. Having given advance notice of their intentions and schedule, the airport was mobbed with more than 30,000 people, cheering and welcoming them back to terra firma. In all, the Key brothers and their support crew had done more than 100 refueling operations — with but one failure, though it was a serious one. They had passed perhaps 400 containers of supplies, food, water, toiletries and even changes of clothes. In the 653 hours, 34 minutes that they had been airborne, they had burned 6,000 gallons of fuel, flew more than 52,000 miles while orbiting Meridian, and — most important of all — they had saved their beloved airport and home from bankruptcy and closure.

Meridian Municipal Airport and “Ole Miss”

Today, Meridian Municipal Airport remains alive and well, though it is now known as Meridian Regional Airport (and also as Key Field Air National Guard Base). Fittingly, it is home to the Mississippi Air National Guard’s 186th Air Refueling Wing (186 ARW), which had undergone conversion to C-27J Spartan aircraft but will be returning to tanker operations in just five days, on June 10, 2013, when it will receive the first of its newly re-engined KC-135R Stratotankers. (We take this opportunity to salute the men in uniform with the 186 ARW — thank you for your service!)

Thus, Meridian’s airport is open and operational, receiving military, general aviation and commercial flight operations on a daily basis. Of note, during World War II, the airport was contracted to the USAAC (and later USAAF) for flight training. The runways were paved and lengthened (the main strip is 10,003 feet long!) and the facilities considerably upgraded, including the addition of a control tower and new hangars. Fred and Al Key both volunteered to fly for the US Army Air Corps and both flew B-17 Flying Fortress bombers over Germany. Against steep odds, both completed their combat tours and successfully and returned home to their beloved Meridian.

The fueling system designed by A.D. Hunter was so good that it was adopted — virtually unchanged — by the USAF. Today, the A.D. Hunter refueling system is the worldwide standard for all aerial refueling operations — even copied (or perhaps we should say “reverse engineered”) by the Soviets during the Cold War. Today’s KC-10 Extenders, among other dedicated aerial refueling aircraft, still rely on Hunter’s revolutionary design.

As for “Ole Miss”, that famous plane, still in its original configuration with the catwalks, fuel tank and other modifications in place, was donated to the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum in Washington, DC, where it is now on display. To deliver it, the Key Brothers flew it to Washington, DC, in 1955. The record the Key brothers set back in June/July 1935 — 78 years ago — it still stands even today. It remains unassailed, unbeaten and forever unbelievable that two local Mississippi men, with just the help of their friends and neighbors set one of the ultimate records in endurance flying.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question (and Request!)

In 1934, local songwriter Lula White composed a ragtime song in honor of the upcoming flight of the two Key brothers. Does anyone have an audio file or YouTube video of the song being performed? If so, we’ll link it here!