Published on June 4, 2013

In 1935, after two failed attempts. two brothers took off on a third try, hoping to set a record and save their local airport. Their airplane was a diminutive Curtiss Robin, a favored plane for 1930s era record attempts. Even though they had no backing from any major aviation firms, they were not unprepared, having done extensive modifications by enlisting the help of others in the local community to make special equipment for the flight. Their goal was not global, nor was it expansive with extraordinary press coverage. They had no publicist like the big name aviators of the day. They had no popular following. They didn’t even have a mascot. They wanted just one thing, to save their small town’s hard pack dirt and grass runway airport from closure. The year was 1935 and America was at the height of the Great Depression. The airport they wanted to save was known as Meridian Municipal Airport, a small town in Mississippi.

For others, such a small town airport was just a minor point on the map. To them, however, the airport was also their home, since they lived upstairs in the main building with their wives and kids, running their business right from the kitchen table.

The Key Brothers

Fred and Al Key weren’t well-known aviators, nor were they rich. Everything about their flight was borrowed, built locally, created as jury-rigged, if well-built modifications done by local welders, machinists, craftsmen and friends. The townspeople of Meridian, Mississippi, had donated enough money for fuel and parts. A friend had loaned them the airplane. He and another friend volunteered to fly refueling missions in another Curtiss Robin. The record they hoped to beat was no small matter — they would have to fly more than 23 days non-stop with air-to-air refueling to break the existing record that had been set in Chicago. If they could do it, they reasoned, they might just save their airport from returning to its former “glory” of being just another cotton field in America’s South.

Fred and Al Key had been inspired to learn to fly during the last year of the Great War of 1914-1918 when several American planes had landed in a nearby farm field. They subsequently trained at the Nicholas-Beazley Flying School in Marshall, Missouri, before opening their own flight school. They came back to Meridian as the returning local boys, now rated pilots, and with a dream of running a business and, on the side, breaking the 8 day record of flying around the world. Without funding or sponsorship, however, they couldn’t hope to challenge that lofty record. Moreover, coming from Meridian, few would be interested in supporting their dream. They continued to teach flying lessons and fly small-time commercial operations while they moved into the airport’s main building and started to raise their families.

Flight Preparations

Locally, they were well known fixtures at the airport. As a result, with the airport faltering from the financial strain of the Great Depression, they knew they had to do something. There seemed no better way to save the airport than to set a record by flying around the local area. But what record could anyone possibly set in the local area? That was how they hit on the idea of an endurance flight — the existing record, set up in Chicago, was at 533 hours. That was achievable and, even better, they would fly circles around Meridian, day and night, the perfect advertisement for the airport itself. Setting such a record, however, was a tall order. To overcome that, they did some quick calculations and worked out that they would need over 5,000 gallons of gasoline — a cost that already exceeded their budget. And so, as the idea of saving the airport was in line with their fundraising, which would increase local awareness of the importance of Meridian’s own airport, they turned to the public for the help. They didn’t have to wait long.

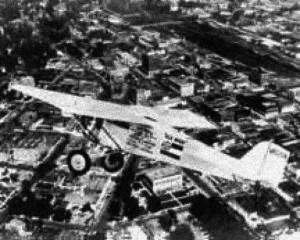

The first challenge was the airplane. A Curtiss Robin was loaned by William H. “Bill” Ward, Jr., another local pilot — it carried the name “Ole Miss”, a salute to their southern roots. It was a single engine aircraft, powered by a five cylinder Wright Whirlwind radial that offered 165 hp. This also made it a fairly fuel efficient and reliable machine — it was also a familiar plane and one they had flown before. In addition, the Curtiss Robin and the Whirlwind engine were well known among aviators seeking to set endurance records. However, there was no way that engine could make it to 533 hours or more without maintenance. The fuel tank wasn’t large enough either. Nor was there anyplace for a pilot to sleep while the other flew. How would they pass fuel, oil, parts and, above all, food and water for the pilot? How would they change the oil?

Innovating the Refueling System

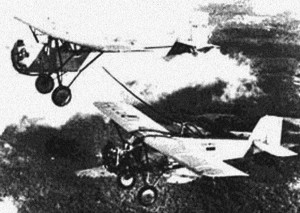

The most dangerous thing was the aerial refueling. Existing methods, which had only been tried in the previous dozen years or so, had been to pass a hose from one plane to the next. Time after time, the wind would buffet that type of refueling hose and dose plane, pilot, crew and interior with raw fuel. On board fires were a risk, as well as petroleum poisoning from skin exposure, breathing fumes and more. The handholds on the hose were particularly dangerous — in the years leading up to their flight, one man had been killed trying to refuel when the prop had snagged the hose, twisted onto his hand and dragged him into the spinning prop.

There were no other in-flight refueling designs — and so the brothers turned to another local man named A. D. Hunter for help in designing some sort of coupling system that would prevent fuel spills and arrest the flow when the hose was discounted. Above all, the system would need to eliminate any requirement for the crew to manually handle the hose. Only then would such a system would allow fairly high volume fuel transfers without significant risk. A. D. Hunter, who had only a 9th grade education but was locally known as a genius, delivered exactly what was needed — an automated refueling boom that was based on the same concept as a gas station’s air hose, the same type as used to fill tires. Much larger than an air hose, however, the fuel would still only flow when the connection was made and, due to heavier loads and stresses, it would be more robust and durable.

Other Key Innovations

For engine maintenance, they built a narrow catwalk gangway along both sides of the fuselage. If the engine started running rough, Frank Key, who was the smaller of the two men (thus producing less wind resistance), could climb out onto the gangway, affix himself with a safety line, and clamber forward to the nose. Once there, inches from the spinning prop, he could change spark plugs, clear or replace filters, swap or repair hoses and even change the oil (a special system was engineered to perform that feat as well). From the gangway, he could even clean the windshield which, after days of flying, was an essential task. For maximum safety, Al would throttle back to 80 mph while Fred was outside.

Another major innovation had to do with the fuel system. The passenger compartment of the plane was modified by a local welder named Frank Covert. He removed the back seats from the plane and inserted a huge fuel tank that he custom-built for the operation. The front of it was crafted into the shape of a pilot seat and the back fashioned into a long, narrow bed for one to use when sleeping. The center section was welded into a raised table area for planning, writing notes, and eating. Ultimately, he filled the space with a perfectly welded tank that held 150 gallons, enough to get the pilots through the night with ease since the engine burned approximately 9 to 10 gallons per hour.

Finally, a VHF radio was installed — it was another innovation, the first VHF radio installed in an airplane, which offered much better air-to-ground communications without the tiring noise of static that was the norm for HF systems.

Ready to Fly

Finally, the Key Brothers were ready to fly. Their first attempt ended badly with mechanical problems. With those fixed, some days later they tried again. After a time aloft, however, the weather forced them to cancel. Throughout, they enjoyed the dedicated support of their wives and families.

On June 4, 1935 — today in aviation history — the two Key Brothers took off for the final time, aiming to go as long as they could, not just surpassing the 533 hour mark (23 days) but crushing it.

What a great story!!!!!

Interesting! but so far I have heard about refueling the plane, oiling the plane, repairing and even cleaning the plane. I see the crew have a place to work and sleep. I assume the refueling plane somehow lowers more food and water to the crew as well. But………where was the port-a-potty welded to? 🙂