Published on August 15, 2016

By Thomas Van Hare

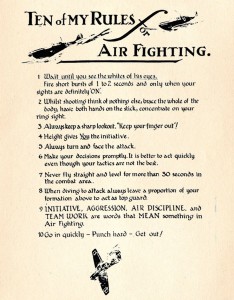

During the Battle of Britain, in nearly every RAF operations hut, you could find a small poster on the wall entitled, “Ten of My Rules for Air Fighting”. Written by the RAF ace, Adolph Gysbert Malan DSO & Bar DFC (aka “Sailor” Malan), these rules of aerial combat saved many lives and provided the basis for the tactical mindset of the RAF fighter arm. Like the Dicta Boelcke from the early days of World War I, Sailor Malan’s rules are at the very foundation of a fighter pilot’s training. Most of the rules apply even today, more than 75 years after they were written.

The Ten Rules

Sailor Malan’s Ten Rules were as follows (as emphasized with underlining in the original):

TEN of MY RULES for Air Fighting.

- Wait until you see the whites of his eyes. Fire short bursts of 1 to 2 seconds and only when your sights are definitely ‘ON’.

- Whilst shooting think of nothing else, brace the whole of the body, have both hands on the stick, concentrate on your ring sight.

- Always keep a sharp lookout. “Keep your finger out”!

- Height gives You the initiative.

- Always turn and face the attack.

- Make your decisions promptly. It is better to act quickly even though your tactics are not the best.

- Never fly straight and level for more than 30 seconds in the combat area.

- When diving to attack always leave a proportion of your formation above to act as top guard.

- INITIATIVE, AGGRESSION, AIR DISCIPLINE, and TEAM WORK are the words that MEAN something in Air Fighting.

- Go in quickly – Punch hard – Get out!

Who was Sailor Malan?

Adolph Gysbert Malan was born in South Africa in 1910 and was 30 years old at the time of the Battle of Britain. He had joined the RAF at age 25 (in 1935), when the RAF began its expansion in the years leading up to WWII. At the height of the Battle of Britain, he was the commander of RAF No. 74 Squadron. In large part due to his leadership qualities, maturity, and skill, the unit became one of the top squadrons in the entire RAF.

Malan’s nickname was “Sailor” and modern generations of pilots have little idea of his actual given name — and even if they did, few would pronounce it well enough to do the man justice. Thus, most know him today simply as Sailor Malan. In the months leading up to the beginning of World War II, Sailor Malan was a Flight Lieutenant serving in a Spitfire squadron in France.

After a false start when the squadron was ordered to intercept “enemy planes” that turned out to be returning RAF bombers, No. 74 Squadron had its first combat engagement on September 6, 1939. Once again, however, the engagement turned out to be RAF planes returning from a mission. This time, the unit misidentified the planes as German, and Acting F/L Sailor Malan ordered an attack. In the ensuing melee, his flight downed two RAF Hurricanes. Later on, the engagement was called the “Battle of Barking Creek”. A series of courts-martial followed for all involved. Despite apparently lying to cover up his own responsibility in the matter, in the end, Sailor Malan was acquitted of all charges — a war was on and probably the courts-martial recognized that mistakes happen. Above all, there was a shortage of pilots, which also tempered the zeal to pursue the case.

It wasn’t long afterward that Sailor Malan began racking up kills. By the time of Dunkirk in June 1940, he had become an ace with five confirmed victories. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his deeds. Fighter tactics were steadily evolving under Malan’s leadership and the RAF followed his lead abandoning the “Vic formation”. That ill-fated tactical formation was better suited to parades than combat flying. No. 74 lead the way by mimicking the German “finger four”, a formation that they had seen firsthand in combat, recognizing its advantages.

By the time of the Battle of Britain, Malan’s promotion was affirmed as a full Flight Lieutenant. On August 8, as the Battle of Britain raged, he was given full command of RAF No. 74 Squadron. Three days later, under his command, the squadron claimed 38 enemy aircraft downed, the day is thereafter known as “Sailor’s August the Eleventh”. Days after that, he received his second DFC.

Following those events, Sailor Malan steadily continued to score victories. He also received the DSO. However, his war in the air officially ended in 1941, when he was ordered to “fly a desk”. As consolation, he was given command of Biggin Hill Airfield. He ended the war — a survivor perhaps in large part because he had been assigned to a desk (at which he bridled) — with 27 confirmed kills, 7 additional shared, three probables, and 16 damaged enemy aircraft to his official credit.

A high point of his late war experience was leading the 145 (Free French) Fighter Wing and flying over the beaches of D-Day on the afternoon of June 6, 1944. It was a proper way to return to France, a country he and his mates of No. 74 Squadron had left “in a hurry” just prior to Dunkirk in 1940.

End Notes

Sailor Malan’s post-war life back in South Africa was tumultuous. Never shying from a risk, he headed up a group of anti-Apartheid veterans called, “Torch Commando”. Under Malan’s leadership, the organization grew to over 250,000 members. He never lost his fighting spirit, despite being ostracized by the government of South Africa for his political position. Being a war hero, however, insulated him from much of the retribution the Government of South Africa would have liked to dish out.

Sadly, Sailor Malan died in 1963. He was finally downed by Parkinson’s Disease. Based on his popularity in South Africa, an endowment was raised in his name as a research fund dedicated to uncovering the causes of Parkinson’s. Sailor Malan’s fund remains engaged and active today — in that regard, his last battle is still ongoing.