Published on December 7, 2016

By Thomas Van Hare

Exactly 75 years ago today, on December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, catching America by surprise. From the first minutes of the attack, the Japanese took out most of the fighter aircraft at the island’s airfields, leaving their dive bombers and torpedo planes free to execute their attacks without fear of fighter interception. As a result, what was likely the first American plane to take off that day wasn’t a fighter plane, but rather an unarmed, twin-engine scout seaplane, a Sikorsky JRS-1 flying boat. The Navy seaplane was piloted by Ensign Wesley H. Ruth of US Navy Utility Squadron One (VJ-1) on a mission to search for and find the attacking Japanese fleet.

By chance, their assigned course took them directly to the Japanese fleet — and but for two degrees of heading, history of the war quite nearly changed that day.

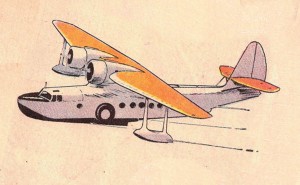

An Unlikely First Plane to Fly into Danger — the Sikorsky JRS-1

In the three years leading up to Pearl Harbor, the US Navy had procured 17 of Sikorsky JRS-1 flying boats for scouting and aerial photography. Ten of those were assigned to a single unit, Utility Squadron One (VJ-1) and were based on Ford Island, right at the epicenter of the Japanese attack. Ensign Wes Ruth’s seaplane, the 13th built in the series, was delivered in 1938.

Ensign Ruth’s squadron was primarily tasked with duties as a photographic unit for the US Navy’s Pacific Fleet. The squadron’s flight crews were trained additionally in fleet reconnaissance and antisubmarine patrol. However, the Sikorsky JRS-1 was an unlikely combat plane. It was slow, with a maximum airspeed of just 105 kts. It boasted just 875 hp of power. It was unarmored and unarmed, without defensive machine guns.

In fact, the US Navy’s Sikorsky JRS-1 was little more than a stripped down, militarized version of the proven civilian airliner, the Sikorsky S-43. In turn, that plane a smaller version of the more famous and larger Sikorsky S-42 “Clipper”. The S-43 was known as the “Baby Clipper”. In civilian service, the “Baby Clippers” flew with Pan Am, among other airlines, plying the skies with short passenger flights. A common route was to carry passengers from Miami to Havana, Cuba, as but one example. In its military configuration, the JRS-1 had a maximum range of just a bit more than 500 nm plus a bit more for fuel reserve. It’s only weapons were that it could carry a few small depth charges to use in the event of having to hunt submarines.

Setting the Scene

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Utility Squadron One’s JRS-1 seaplanes were lined up beside the runway. They were easily identifiable, painted brightly in a color scheme that was entirely ill-suited for the war that had so unexpectedly begun. The fuselage was bare metal silver and the wings and tail were painted in bright orange and yellow to ensure that the seaplanes could be easily spotted from afar while flying their photo missions. Thus, Ensign Ruth took off that morning knowing full well that if spotted, he was a sitting duck. He flew anyway, hoping beyond hope to find the Japanese fleet and report its position back, so that the US Navy’s fighters and bombers could get a chance to fight back.

Ensign Ruth’s Mission

When the first Japanese bombs began to fall, Ensign Ruth was eating breakfast in the mess hall at the Ford Island base’s BOQ — the Bachelor Officers Quarters. He watched calmly as the first wave of Japanese planes descended toward the fleet anchored around Ford Island, thinking it was a mock attack by the US Marine Corps flyers, as had happened many times before. He realized quickly that it was an attack when the first planes began dropping bombs on the nearby Navy PBY base.

Grabbing his cap and coat, he abandoned his breakfast and ran through the lobby of the BOQ. He stopped briefly to help several some civilian families who had run inside seeking shelter and then realized that he should get to the flight line. He jumped into his personal car, a convertible, and drove with the top down as fast as he could to the airfield. As he drove, he thought that he was on a “one-way trip” that would end in his death. He scanned the skies as he drove. Japanese planes crisscrossed the skies, making repeated attacks against the Navy’s many ships anchored around the base.

He felt exposed and at risk of getting strafed. However, the Japanese planes were more focused on the great battleships in the harbor. They either didn’t notice or didn’t bother to go after his single car as it raced along one of the island’s few roads toward the base. Just as he arrived at the north end of the airfield’s single north-south runway, about a quarter mile from the battleship USS Arizona, the ship took a direct hit by a Japanese bomb.

The forward magazine on the Arizona exploded in a great flash and the ship’s entire front section blew up, sending a massive cloud of black smoke in the sky. The battleship’s powder pellets — each one “about the size of my middle finger,” he later said — rained down around and into his car as he entered the base, as he put it, “like snow” falling. Pulling up at one of the squadron’s hangars, he parked and made his way to the squadron’s ready room. Along the way, he passed a line of dead bodies that were lined up by the hangars.

A rushed pre-flight briefing followed. As quickly as Ensign Ruth could get a crew together, he raced out to one of the awaiting JRS-1 seaplanes. His hastily assembled flight crew included a total of six men — himself, a copilot, a radioman, and three sailors who were to perform as spotters searching for the enemy fleet. All but Ensign Ruth were enlisted men, even including the copilot. These men had been drawn from those who had made their way to the airfield. Other flight crews were steadily coming to Ford Island on board the many small boats that braved the journey even as the Japanese planes were in the midst of their aerial attack. Within hours, all ten of the JRS-1 flying boats were airborne performing search missions all around the ocean surrounding Hawaii, manned by these crews who risked it all to get to their battle stations.

As Ensign Wes Ruth was preparing to take off, unexpectedly the commanding officer of the sister squadron, VJ-2, ran out to his seaplane. The officer handed each the three sailors on the seaplane a WWI vintage M1903A3 Springfield bolt-action rifle as well as a little ammunition.. With those rifles on board, they were no longer “unarmed”, though it is questionable that single-shot rifles were much of a match against any of the Japanese fighter planes, which carried multiple machine guns and wing-mounted cannons each. As it was, since the Sikorsky JRS-1 didn’t have gun positions or even an open cockpit or shooting position in the back. The only way to fire out of the seaplane would have been to first shoot out the windows in the back. None of the flight crew held any illusions about their chances of success.

An Incredibly Fortuitous Course

Ensign Ruth’s orders were to fly a search mission heading due north first for 250 miles, then turning to fly due east for 10 miles before turning back south for a return flight to Oahu. Though nobody realized it, at that moment the Japanese fleet was located directly north of Oahu, almost exactly 220 miles away, right on his course line and near the turn point at the end of his assigned line.

Amidst the chaos of the aftermath of the Japanese attack, Ensign Ruth took off and headed north. As the seaplane banked around to the north, the Japanese fleet was still heading south, intent on reducing the distance its returning planes would have to fly to get back on board. As the JRS-1 trundled along, however, the returning attack planes were already ahead and nearing the Japanese fleet. As they came in, the Japanese fleet altered course to 315 degrees, turning into the wind to facilitate recovering their planes.

Meanwhile, lacking any hope of defending himself against any fighter cover, Ensign Ruth’s only hope was to avoid detection by flying just beneath a broken layer of clouds at 1,000 feet of altitude. He skimmed along just below as all eyes searched the water for any sign of the enemy fleet, planning to duck into the clouds to avoid detection if any enemy planes or ships were spotted, and then make his escape as they radioed in a report. The sailors in the back of his Sikorsky, however, were at the windows, scanning both the skies and waters while holding their Springfield rifles, ready to shoot at whatever they spotted.

For slightly more than two and a half hours, he flew north at the JRS-1’s normal cruising speed of 95 knots. Finally reaching a point 250 miles north of Oahu, Ensign Ruth turned to the east and flew his assigned ten miles. Then he turned back south. What he didn’t know was that the Japanese fleet was perhaps only 30 miles to directly west of his search track, directly parallel to the point where he had made his turn eastward. Had he been assigned to turn westward instead, he would have likely flown into the midst of the entire Japanese fleet as it was recovering the planes from the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Neither the enemy or Ensign Ruth’s crew spotted each other. Instead, the JRS-1 finished its eastward leg and Ensign Ruth turned south to fly another two and a half hours back to Ford Island. On the way, the crew excitedly reported another airplane that following behind and below. As they neared Kaneohe Bay, across the island from Pearl Harbor, Ensign Ruth quickly descended to get below the unidentified aircraft. Cautiously, they watched as it flew onward into the distance, apparently not noticing them. If they had been engaged by the aircraft, which they assumed to be enemy, by flying low he hoped that the sailors in back could have shot back with their rifles out of the seaplane’s side windows in the rear fuselage. Weeks later, he discovered that the other aircraft had been just a civilian plane that was out dropping parachutists that day.

The flight across the island to Ford Island passed uneventfully. However, when the seaplane arrived back at Pearl Harbor, the anchorage was a fiery scene of destruction. Sunk and damaged battleships, cruisers, and support vessels littered the harbor. A panorama of chaos was on display in front of his seaplane, with fires burning at the surrounding airfields as smoke blotted the horizon.

He turned the JRS-1 toward the single north-south runway on Ford Island and set up for a landing. As he came in, he was shocked to find trigger happy antiaircraft gun crews shooting at his airplane. The gunners were blazing away at anything that was flying, thinking the air was still full of Japanese planes, despite that the attack had ended hours earlier. In the confusing period after the attack, several other US Navy and Army Air Corps planes were shot down by friendly fire. Others were badly damaged while attempting to land, including many of the US Army Air Corps’ new B-17 Flying Fortress bombers that were coincidentally scheduled to arrive that morning after a long over water flight from California.

Despite the friendly fire, Ensign Ruth was able to land safely. He shut down and reported back to the ready room for debriefing. While inside, his plane was loaded with depth charges (the only armament the “Baby Clipper” could actually carry). He was soon sent back out to hunt for enemy submarines — none were found.

Despite every effort, the Japanese fleet had slipped away undetected. The disaster that was Pearl Harbor had ended.

Aftermath and Conclusion

In weeks after the devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, Utility Squadron One flew many missions, including numerous aerial photography sorties to document the damage to the Navy’s fleet and facilities at Pearl Harbor from the air. Today, except for the few photos that were taken from Japanese planes, the squadron took almost all of the photos at Pearl Harbor, including those taken during the attacks of ships exploding and sinking, of men fighting the fires. The photographers assigned to Utility Squadron One had all run out of their photo lab with their cameras. Exposed and in the open, they started taking pictures, despite the extraordinary risks involved — they survived and provided the best record of the attacks that day.

Regarding his mission, in retrospect, had Ensign Ruth’s Sikorsky found the Japanese fleet, an immediate counterattack would have been almost certainly ordered. There were several hundred American fighters and bombers on the US Navy’s aircraft carriers available for that, though more than 350 Army planes had been destroyed. All of the US Navy’s aircraft carriers were untouched, having been at sea when the Japanese attacked the anchorage.

While the counterattack might have dealt some damage to the Japanese fleet, in hindsight, it seems more likely that they would have fared badly against any defensive air patrols mounted by Japanese fighters. The under-appreciated Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero would later teach many hard lessons when the US Navy first tangled with the Japanese. Their pilots were experts, they had superior equipment, and they flew with brilliant tactics and skill.

It is hard to say what might have happened — but in the months afterward, the stage was set to settle the score with the Japanese on much better terms at the Battle of Midway, where, aided by the decoded signals of the Japanese fleet, the Americans capitalized on Japan’s vulnerabilities and sank much of its fleet. Had Ensign Ruth spotted the Japanese ships that day, the resulting engagement would have not only changed history but might well have spelled defeat for the US aircraft carriers. Had that happened, it would have left the US Navy without the aircraft carriers it needed later to turn the tide of the Pacific War.

Ultimately, the bravery of Ensign Ruth’s flight crew was recognized fully by the US Navy. For his initial mission that day — flying first, alone, quite nearly unarmed, and against all odds — he and the other five men on his crew were awarded the Navy Cross. It would only be much later that analysts would realize just how close his flight had actually come to finding the Japanese fleet.

Ensign Wes Ruth survived the war and lived to 101 years old. He passed away on May 23, 2015. The Sikorsky JRS-1 that he flew that day, as unlikely as it sounds, is still with us today. You can visit it at the Smithsonian’s Udvar-Hazy site at Washington-Dulles International Airport where it is undergoing restoration to the paint scheme it bore that day at Pearl Harbor.