Published October 23, 2017

By Thomas Van Hare

“Our job tomorrow will be to take off well before daylight for the first time in history and bomb the gun positions and defenses on the landing beaches themselves little more than half an hour before troops are set to land. The six-ship takeoff will be used. Briefing is at three a.m. and the 320th will take off just a few minutes before the 319th.” — 319th Medium Bomb Group Mission Log, August 14, 1944

Decimomannu Air Base in Sardinia was the temporary home of the longest serving group in the Mediterranean theatre, the 319th Medium Bomb Group of the 12th Air Force. Flying Martin B-26 Marauders, the 319th had been bombing communications links, gun positions, and key bridges supplying the German Army in Italy and France. The invasion of Southern France (Operation Dragoon — the so-called, “Second D-Day”) was set for August 15, 1944, and the 319th would be in the thick of it.

The upcoming mission would involve a “six-ship takeoff”, a practice the group had pioneered in April 1944, just four months earlier. To do a six-ship takeoff by day was extraordinary — that the group pulled it off at night is almost beyond belief. Scant practice was afforded, despite the challenges and on August 12, just three days before the invasion, the 319th’s SECRET mission logs recorded the preparations, “The group carried out four six-ship takeoffs and landing in the dark early this morning preparatory to employing them on night missions.”

The Six-Ship Takeoff

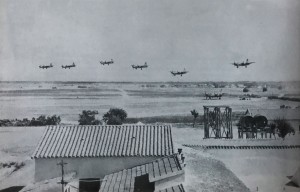

The six-ship takeoff was detailed a month later in the USAAF publication, IMPACT, a classified magazine for military distribution (at the time marked CONFIDENTIAL and long since declassified). The report included photos of the 319th’s base at Decimomannu and diagrams showing how the group, using their then-secret method, could field an entire squadron of 24 bombers in the time it took other bomb groups to launch just eight aircraft. The report highlighted that the 319th’s method shaved up to 25 minutes from the time it took to launch and assemble formations for each mission — critical minutes of extra fuel and bomb-carrying capacity that the practice afforded.

The magazine IMPACT described the procedures in some detail:

“All four flights of a 24-ship mission line up before the first starts off, in assembly as shown in the diagram directly below. With manifold pressure pushed to about 25 inches, the pilots release locks and hold the brakes by foot. At the flag, the pilots let go the brakes and start easing up their throttles. From the start, wing men fly on element leaders to the line even. First pilots concentrate on throttling to keep abreast, relying on the co-pilots to handle the other gadgets. A fifth of the 6,000 foot runway is used in getting up to full throttle, and the deliberate easing of throttle makes necessary the use of about 600 feet of runway in excess of that needed for single-ship takeoff.”

By August 1944, the 319th had performed four months of six-ship takeoffs flawlessly — described in IMPACT as “more than 100 missions without mishap”.

Join-Up Patterns

Another key innovation were the methods of joining up into a combat formation after takeoff. This entailed some thoughtful planning and practice. Once formed up, the Bomb Group could proceed directly toward the target.

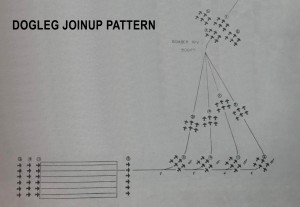

“DOGLEG JOINUP PATTERN is demonstrated by the diagram. The first flight off (No. 2) flies for five minutes, the others, at 1-minute intervals, for 4, 3, 2. The turns are 120, 107, 93, and 80 degrees, respectively, The first flight, maintaining 175 mph, is at bomber R/V 5 minutes after the first turn, at 1,500 feet. The Group CO estimates this pattern puts the formation on course only two minutes later than one taking off on course and closing by speed differential.”

The second pattern involved a “racetrack” circle over the base, after which the 319th could assume the most direct course toward the target. IMPACT described that as follows:

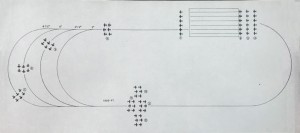

“ELLIPTICAL JOINUP is shown by the pattern diagrammed above. Takeoff, unlike that for the dogleg is in order of flights. The takeoff interval is one minute, and each flight makes its first turn at 30 seconds less, from the end of the runway, than that of the preceding flight. The flights turn 360 degrees, each in a tighter ellipse than its predecessor. Bomber rendezvous is at 1,200 feet, and the on-course position accomplished over the field at 1,800 feet, just 12 1/2 minutes after takeoff.”

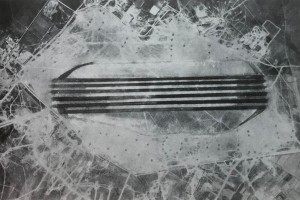

The runways at Decimomannu Air Base were specially-prepared for the six-ship takeoff. Six parallel runways featured oil poured over the hard-packed dirt and sand of Sardinia. This helped reduce dust from prop blast and ensure that the tires didn’t cut deep ruts when moving at high speed.

“STRIPED RUNWAY used for the six-abreast takeoffs and landings is shown below. Width of runway is 1,000 feet. It is divided into the six lanes by the simple expedient of oiling the dirt and gravel surface in strips as shown here. the six planes of the first-off flight line up on yellow-painted tire scraps centered in each of the six lands, the others lining on the plane ahead, all being in position before the first starts away. Danger of collision is in takeoffs and landings has been found to be practically nil.”

What Goes Up Must Come Down

After pioneering the six-ship takeoff, it seemed natural for the 319th to employ a six-ship line abreast landing as well. Like the takeoff, landing the entire bomb group six-abreast saved a lot of time, allowing the Bomb Group to conserve precious fuel and reduce the time it took to bring everyone in after a mission.

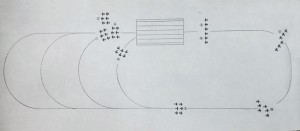

“THE FORMATION LANDING is completed in 8 1/2 minutes from the time the returning mission reaches the field, cutting 9 minutes from the time the crews of the last planes in formation spent circling the field for ship-ship landings. The formation is over the field at 2,000 feet. The No 3 (inside) flight breaks off in a half needlewidth turn. The succeeding flights, in the order 10402, break at 30-second intervals, each describing a 360-degree ellipse 30 seconds longer than the one ahead. Flights turn off the downwind leg for the approach 45 seconds past the end of the runway, the second element uncovering to the inside of the turn. Landing interval is one minute.”

Invasion Day — Southern France

“Virtually the entire group got up at two-thirty today. Those not scheduled to fly or who didn’t have to get up for other duties got up anyway out of excitement to watch the show and be ready to lend a hand where possible. By the time the 320th started taking off, before five a.m., most of the 319th spectators and crews, including a number of ground men who volunteered and got permission to go along in order to see the invasion, were on hand on the field looking on. Two searchlights at the starting of the runway furnished a dramatic glare in which the airplanes, lighted at wing tips and tail, lined up.”

The stage was set for the launch of both bomb groups. After four months of “mishap free” takeoffs, attempting the six-ship take off at night proved more challenging in practice, however, with a full load of bombs, ammunition, and fuel.

“One 320th ship crashed into a hill a mile or two beyond the runway and burned. It was a discouraging sight for the 319th crews, none of whom had ever taken off in the dark before in B-26’s. Then a second ship crashed closer to the field and, a few minutes later, a third failed to get off. The latter two ships also caught fire, exploded and burned. The tension was terrific. Men wondered aloud if the crew members had been able to get out of the unlucky ships before the explosions and made arrangements among themselves as to just what crew members in their own ships were to use what escape hatches in the event of a crash. But, using the six-ship takeoff, every 319th airplane got off safely. The group had the unequaled number of 74 airplanes over the target, the most put up by any group in the wing. In the 437th, which put into the air every one of its 20 ships, three crew chiefs got sick from nervousness after their airplanes had got safely into the air. One crew chief, whose 90-mission airplane went on two missions during the day, was seen to light his cigarette and then throw away his lighter away like a match.”

For the 319th, the mission went perfectly, as described in the 319th mission logs:

“Over the target clouds were pretty thick, but, with an area target, a strip of beach seven-eighths of a mile long, the group dropped its bombs, identifying its position through breaks in the clouds, and got an amazingly good coverage. The only flak opposition was a barrage put up over a town a mile away from the formation. There were no enemy fighters encountered. Ont the other hand, Beaufighters, P-47’s Spitfires, Warhawks and carrier-borne Hellcats wheeled around over the beaches like seagulls looking in vain for opposition. As the 319th formation broke away from the coast after loosing its bombs a formation of silver B-24’s crossed over it at right angles heading out to sea about two thousand feet higher. Warships below could be seen firing at the shore, carriers were poking around with planes taking off and landing on them, and clusters of ships were maneuvering here and there off shore. As the last 319th wave pulled away from the beaches the ships below began moving in toward shore for their eight o’clock landing.”

The day’s entry ended on a positive note, stating first — “Colonel Holzapple expressed himself as very pleased with the job.” And then, a fitting end of the day, the 319th’s log states, “Not a single airplane was lost by the 319th during the day.” Of course, the 320th, flying from the same base, had suffered terrible losses just in the takeoff.

An additional reminder of the unpredictable nature of war came just two days later, highlighted with this entry in the 319th’s log for August 17, 1944. Luck was with them that day too, however, and there were no casualties:

“An entirely-messed-up 24-ship mission got no bombs closer to coastal guns near Toulon than half a mile away. One flight had every ship damaged by flak, but the other flights had only a couple of ships apiece with a couple of holes in them. Part of the mess was due to a bad turn on the part of the first flight on the approach to the target and the lead bombardier forgetting to turn on his intervalometer. Critique was pretty gloomy as a result.”

Additional Notes

Though the six-ship takeoff and landing served the 319th and 320th Medium Bomb Groups well throughout the late period of the war, the practice was not adopted other groups. In many cases, single plane-width runways were all that were available — as was the standard for all of the Stations in England, for instance. In other cases, the knowledge of the methods used was ignored or unavailable to those who might have benefited from the practice. After the end of World War II, the USAAF (and subsequently USAF) did not continue to use the 319th’s six-ship takeoff method, despite its obvious benefits.

Decimomannu Air Base, where the 319th Medium Bomb Group was based at the time, remains a military airfield to this day. Gone are the six parallel strips of oil-soaked dirt. Today, the field has but two parallel runways. Of course, these days, it is rare to see raids at the scale that were regularly practiced during World War II. Hopefully, the world will never see another “thousand bomber raid”, and even the 319th’s raids, with 20 to 76 aircraft in formation at once, are rare. There seems little need to launch six planes at a time and, even if they were launched, modern warplanes usually form up for the attack only after a round of aerial refueling. The bottleneck, it seems, has more to do with the limitations of tankers than multiple runways.