Published August 14, 2012

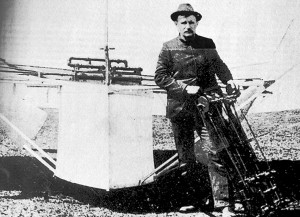

It was dawn when Gustave Whitehead, a German citizen living in Fairfield, Connecticut, powered up his Aeroplane No. 21. “By this time the light was good. Faint traces of the rising sun began to suggest themselves in the east,” the The Bridgeport Herald newspaper report later read. “He stationed his two assistants behind the machine with instructions to hold on to the ropes and not let the machine get away. Then he took up his position in the great bird. He opened the throttle of the ground propeller and shot along the green at a rapid rate. ‘I’m going to start the wings!’ he yelled. ‘Hold her now.’ The two assistants held on the best they could but the ship shot up in the air almost like a kite.”

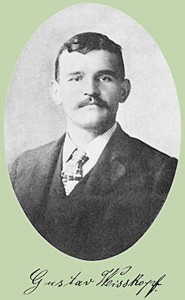

One hundred and eleven years ago today, if newspaper reports are to be believed, Gustave Albin Whitehead achieved the world’s first flight in a powered, heavier than air airplane — two and a half years before the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk. Or did he?

“We can’t hold her!” shrieked one of the rope men. “Let go then!” shouted Whitehead back. They let go and as they did so the machine darted up through the air like a bird released from a cage. Whitehead was greatly excited and his hands flew from one part of the machine to another. The newspaper man and the two assistants stood still for a moment watching the air ship in amazement. Then they rushed down the sloping grade after the air ship. She was flying now about fifty feet above the ground and made a noise very much like the “chug, chug, chug,” of an elevator going down the shaft.

In the years after his supposed flight, numerous attempts were made to investigate the matter. Some concluded that he had flown, while others concluded that he had not. One researcher declared the Bridgeport Herald newspaper article as being little more than “juvenile fiction” though a reading of it today does not appear quite so fanciful. Other researchers went door to door in Fairfield to interview neighbors and those who might have known of Whitehead’s inventions. Most testified to his flights, many with sworn statements, even reporting that on numerous occasions in 1901 and 1902 he had flown not only in nearby fields but also down the streets of Fairfield.

He saw the danger ahead and when within two hundred yards of the sprouts made several attempts to manipulate the machinery so he could steer around, but the ship kept steadily on her course, head on for the trees. To strike them meant wrecking the air ship and very likely death or broken bones for the daring aeronaut.

Several contemporary magazines and reports also carry news of Whitehead’s flights. In two cases, the articles include reports of photographs that the authors had seen but which have long since disappeared. Gustave Whitehead himself stated that his photographs were of poor quality and so he did not wish to publish them. As it happened, the news reporter from the The Bridgeport Herald included a drawing of the “air ship” in its pages — and the editors and staff of the Herald were well known to have been honest and uncompromising in accuracy. This was an era when the reputation of reporters was considered of the utmost importance.

Here it was that Whitehead showed how to utilize a common sense principle which he had noticed the birds make use of thousands of times when he had been studying them in their flight for points to make his air ship a success. He simply shifted his weight more to one side than the other. This careened the ship to one side. She turned her nose away from the clump of sprouts when within fifty yards of them and took her course around them as prettily as a yacht on the sea avoids a bar.

Although most serious historians dismiss the claims of Gustave Whitehead’s first flight, in actual fact the historical record is certainly mixed. On careful review, the matter is far from conclusive and, as such, it would be a disservice to history to make a definitive statement one way or the other. Put simply, evidence exists on both sides, ranging from sworn affidavits from those who claim he didn’t fly (though how they could have witnessed that he “never flew” is a bit of a mystery) to other sworn affidavits from witnesses who state that they had personally seen the flights themselves. There is even one denial from a party who was later revealed to be motivated by the fact that Whitehead still owed him money for work in helping prepare and transport his aircraft for its flights!

He looked back and waved his hand exclaiming, “I’ve got it at last.” He had now soared through the air for fully half a mile and as the field ended a short distance ahead the aeronaut shut off the power and prepared to light. He appeared to be a little fearful that the machine would dip ahead or tip back when the power was shut off but there was no sign of any such move on the part of the big bird. She settled down from a height of about fifty feet in two minutes after the propellers stopped. And she lighted on the ground on her four wooden wheels so lightly that Whitehead was not jarred in the least.

The final injustice to Gustave Whitehead was based on the fact that he born in Germany. Anti-German sentiment was common and, after World War I when his claims were more closely evaluated, that anti-German feeling had reached a fevered pitch. Whitehead never became a US citizen either, despite living in America for more than three decades. Regardless, Gustave Whitehead proved to be an excellent engineer. His innovations included aviation engines that, according to the first report were extraordinarily lightweight and powerful for that era: “The ten horse power engine weighs twenty-two pounds and the twenty horse engine weighs thirty five pounds.”

“I told you it would be a success,” was all he could say for some time. He was like a man who is exhausted after passing through a severe ordeal. And this had been a severe ordeal to him…. And there he sat in silence thinking. His two faithful partners and the Herald reporter respected his mood and let him speak the first words. “It’s a funny sensation to fly.”

It might not matter whether Gustave Whitehead was the first to fly. No doubt the mantle of that success, if indeed it was his to wear, should be worn by Whitehead with pride. In fact, several recent replica aircraft that very closely duplicated Whitehead’s No. 21 design have been flown successfully. At this point, whether Whitehead could have flown seems in little doubt — whether he did, however, may remain a permanent mystery. Nonetheless, it would fall to countless others to carry the torch of aviation history, setting records and making daring, glorious flights. In the end, Whitehead was a much better inventor than businessman. He never capitalized on his aircraft designs, nor his innovative lightweight engine designs, nor the many on other inventions that he pioneered later in his life. Largely impoverished and working in engine repair in his later years, he died of a heart attack in 1927. It was a sad end.

In retrospect, Whitehead’s achievements are best celebrated for what they are. His story does not lessen the achievements of others, whether of the Wright Brothers or of the many other inventors. The fact is, Whitehead’s inventions and achievements stand on their own, whether or not he ever achieved flight after all. He was a brilliant engineer and inventor and, fittingly, has been recognized in more recent days with the title, “Father of Connecticut Aviation” — not bad for a German immigrant who battled racism most of his life.

I’ve studied the Whitehead legend for over 30 years, read everything ever written about him (all of which stem from three books), and have long concluded that the man was a dreamer. None of his contemporaries of the 1901-1916 time period, including Glenn Curtiss, believed him and his claims, so why should we?

By the way, his first “flight” claim was not in 1901, but in 1899, when he allegedly took a two place, steam-powered airplane (the second crew member was shoveling coal) up at night from a field near Pittsburgh. He allegedly flew 600 feet before crashing into the second floor of a hospital! Strangely enough, no newspapers reported it and the Pennsylvania Historical Society can find no supporting evidence of his claim. It seems that airplanes crashing into buildings at night were not newsworthy enough to warrant a story in the papers…. Or maybe it was anti-German bias from a war that was still 15 years in the future.

That story was too outlandish to be believed, so the Whitehead supporters have chosen to overlook it despite it being part of Whitehead’s life story. The Whitehead legend just doesn’t go away, no matter how much truth it is exposed to. But why does it continue to flourish? I believe that it is a case of local “boosterism” by a group in Bridgeport, Connecticut. By the way, the original of the triplane hang glider picture shows it supported by wires.

The man is a fraud.

The length and depth of Carlton’s comments demonstrate clearly that the Whitehead issue remains somewhat contentious, even today. The simple fact remains, there is no solid proof that he ever flew. With that said, it remains a quandary why many of his neighbors and others in Connecticut swore under oath in legal affidavits that they personally witnessed his flights. If he did fly, he did so without effective pilot control, which isn’t technically “controlled flight”. A “pilot” in a No. 21 replica sails along by simply hanging on, barely high enough to qualify as flying but still fast enough to kill you if the machine falls off to the side or noses over. By any stretch of the imagination, that is no great “invention”.

Of note, Carlton’s “hospital” reference is slightly off, but the main point he makes is spot on. To correct the record on that, here is the 1899 story (an excerpt from the January 1935 report in the magazine “Popular Aviation” which was the forum in which Whitehead finally achieved some level of fame):

Whitehead never showed that his flight experiments could be reproduced on demand with witnesses and photographers present. He may have flown briefly — or he may not have flown. Yet still, modern experiments show that he could have flown with the machine that he had — assuming he was lucky enough to not crash. Yet even those tests are somewhat suspect, using modern propellers and, if memory serves, Rotax engines.

The key point is that in the end, he had no lasting impact on the science of aviation — and that is all that truly matters. One could just as well say that João de Almeida Torto (click for story) was the first to fly a powered aircraft in 1540, the “power” being the flapping his arms with his makeshift wings of fabric and wood — Torto died in the attempt. To this day, Portugal holds quietly to the legend that they invented flight — well, maybe some might say that after a few glasses of a fine tawny port anyway.

To me it seems bogus, since there seems no way that they could expect to “hold” a powered aircraft. Where they running alongside? Too fast. Did they have ropes? They would have crashed it — it was not a kite.