Published on August 24, 2012

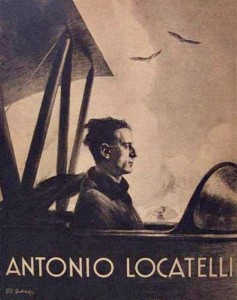

In the Spring of 1924, the United States had set out with its fleet of Douglas World Cruisers, hoping to become the first nation to achieve a flight around the globe. Seeing the successful progress of the Americans, the Italians soon sent forth their own challenge — the pride of Italy would rest on the shoulders of Antonio Locatelli, one of that nation’s greatest pilots and a member of the Italian Parliament. Yet Locatelli’s effort would come to an end in the water, his life and the lives of his crew saved not by providence but by an American Naval cruiser in the storm-rocked seas off the coast of Iceland after four harrowing days adrift.

Locatelli Sets Out

By 1924, aviation’s relentless advance had spanned continents and crossed oceans — the greatest challenge remained to be the first to fly around the world. Sadly for Italy, it appeared that America was far ahead with its three Douglas World Cruisers — “Chicago”, “New Orleans” and “Boston”. The Americans had set out from Seattle, Washington, on April 6, and flown westward to the Aleutian Islands. They had crossed the Pacific by the Bering Strait and by June 3 they were in Kagoshima, Japan. They reached Calcutta, India, on June 30 and then Constantinople (now Istanbul), Turkey, on July 11. Bypassing Italy, they flew across Europe and arrived in London, England, on July 16. There, they had to wait while the US Navy deployed ships in a picket line across the Atlantic to support any planes that might run into trouble.

With the pride of Italy at stake, Antonio Locatelli chose to fly in a lone, unsupported aircraft, a German-designed Dornier J Wal flying boat with a pair of Rolls-Royce Eagle engines. The plane had been built in Italy in the shipyard at Marina di Pisa. It was sleeker and faster than the American biplanes but even so, Italy was the underdog in the race. More critically, the Italians didn’t have the resources to match the American effort. Undaunted, Locatelli set out from the Marina di Pisa in a desperate attempt to catch up. He departed at dawn on July 25, 1924. With Locatelli were two copilots, Lieutenant Crosio and Lieutenant Marescalchi, and two flight engineers, Braccini and Falcinelli. They proceeded past Saint Raphael, then onward to Ouchy and to Strasbourg in Alsace-Lorraine. Meanwhile, the Americans stopped at Brough, England, to change their planes’ wheels for ocean-going floats. Then they flew to Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands in preparation for their crossing of the eastern Atlantic to Hornafjord, Iceland.

The Flights to Iceland

The Douglas World Cruiser “New Orleans” made the flight to Iceland on August 2. Then came the “Chicago” and the “Boston”, departing together on August 3. However, the “Boston” lost oil pressure in its engine and was forced down in the open seas at 3° 28′ W x 60° 40′ N. By dawn on August 4th, the plane was swamped and capsized alongside the US Naval cruiser, the USS Richmond. It was given up for lost and allowed to sink. The remaining two Douglas World Cruisers proceeded to Reykjavik, Iceland. There, they awaited the positioning ahead of supplies by the Danish ship, Gertrud Rask, to Angmasalik, Greenland. However, the Danish ship would find the harbor blocked with ice, forcing the Americans to select another destination in Greenland. Days would pass as the American planes waited at Reykjavik. Finally, Locatelli was able to catch them after passing through Rotterdam in the Netherlands, crossing the English Channel and landing to Hull in England. From there, he proceeded to Stromness in the Orkney Islands. Then Locatelli flew across the open sea to the Danish Faroe Islands (the Færøerne) before making the flight to Reykjavik, Iceland.

Locatelli Catches Up to the Americans

On August 17, Lt. L.P. Arnold, the mechanic for the Douglas World Cruiser “Chicago” reported: “In preparation for the long jump more gasoline was put aboard both planes this morning. The ships today were moving to positions along the new route and by morning all should be in readiness — that is all but the weather & we can hope for that. About noon Locatelli arrived in a keen looking flying boat — monoplane type with twin motors.” With Antonio Locatelli’s arrival, if the Americans gave permission, he could even fly along with them on the upcoming flight to Greenland, the most dangerous portion of the crossing. The US Chief of the Army’s Air Service, General Patrick, gave approval and on August 19, the Americans dined with Locatelli and his copilots, enjoying the conversation and getting to know the Italian flyer.

Meanwhile, US Navy deployed its ships in a line ahead — USS Richmond was on station 90 miles out, then the USS Reid #292, another 115 miles beyond that. Then came USS Billingsby #293 further on another 140 miles and USS Barrey another 150 miles beyond. The planes would then fly over the USS Raleigh 160 miles further on before reaching the Greenland coast 70 miles on. From there, they would fly just 60 miles more to land at Fredriksdal, Greenland. If anything went wrong with the airplanes, they could hopefully alight close to one of the ships for a rapid pick-up.

The Bold Aviators Leave Iceland

On the morning of August 21, the weather reports were finally favorable for the flight. The two American Douglas World Cruisers departed Reykjavik along with Locatelli’s Dornier Wal. However, soon after take off, rather than accompanying the American planes, Locatelli would instead speed ahead in the faster Dornier. Soon, he had disappeared into the distance. The Americans flew onward and for the first 500 miles, the weather was ideal. Then, as the planes passed the USS Barrey, they received a signal for fog ahead. Shortly afterward, they flew into worsening weather. Visibility dropped. Then they flew into heavy storms. They missed seeing the USS Raleigh because they were flying low over the water, dodging around icebergs amidst the storms. Then the two Douglas World Cruisers lost sight of one another. Individually, they each reached the coast of Greenland and proceeded to Fredriksdal, where the Danish cruiser, Island Falk, churned out a column of smoke from its boilers to help guide the planes in. The two Douglas World Cruisers landed 50 minutes apart and were dismayed to learn that there was no sign of Antonio Locatelli, his plane or crew, who should have preceded them in.

On Friday, August 22, Lt. L.P. Arnold, the mechanic of “Chicago” recorded in his logbook: “As yet no word has been received from Locatelli — boats from the Island Falk have been sent to the north & south & rumor has it that a plane was heard passing shortly after our arrival. So perhaps we will have definite information.” Then on Saturday, August 23, Arnold would write more: “All day we expected to hear something from Locatelli but no news came at all — our guess being that he is somewhere on, or near, the eastern coast.” Likewise, Sunday, August 24, would bear no news — the situation for Locatelli was now recognized to be quite desperate.

Finally, on Monday, August 25, 1924, (88 years ago today), there was word — Locatelli and his crew had been sighted in the water after four days adrift. As Arnold wrote it: “Good news greeted us first thing this morning — it being that at midnight the Richmond had picked up Locatelli & his crew — 90 miles east of Cape Farewell. His plane was sunk & perhaps we, better than anyone else, can appreciate how he feels regarding that & also how he feels in having been picked up after drifting so long in a section of the world where boats so seldom travel.”

Locatelli Crosses the Atlantic to Reach the USA.

Antonio Locatelli and his flight crew would be guests on board the USS Richmond for some time. The cruiser would dash eastward to take station between Greenland and Canada in support of the American flight, which was waiting at the jump-off point of Ivigut, Greenland. Finally, on August 31, 1924, the Richmond would greet the DWC “New Orleans” when it set down alongside with engine trouble. While repairs were made, the Americans met with their dashing Italian pilot friend once again, if only briefly before departing for the Canadian shores.

In the end, Antonio Locatelli would cross the Atlantic in 1924, but it would be courtesy of the US Navy. The Italians would shoulder the loss of Locatelli’s plane and take the news as a renewed challenge. As for the American planes, they finally reached Seattle on September 28 and thus completed the world’s first aerial circumnavigation. For his part, Antonio Locatelli returned to Italy with a burning desire to press for a better planned and better supported demonstration Italy’s aviation prowess — this time in an Italian design.

But that is another story….

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

It is amazing how aviation history is often peppered with myths and half-truths. Most people think that Charles Lindbergh was the first to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. He wasn’t — indeed, the Douglas World Cruisers would not only cross the Atlantic, but indeed also the Pacific, all of Asia and Europe — all of that happening three years before Lindbergh would even take off! There were others too who preceded Lindbergh as well. Why was Lindbergh so popular? It was because he flew the Atlantic in competition for the well-publicized Orteig Prize, a $25,000 sum put up to the first aviator to link New York and Paris — and he did it NON-STOP. That was the key. Lindbergh’s famous flight had him aloft for 30 hours, alone in the cockpit of a single engine airplane before reaching Paris. He was a brave man indeed.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

In what year and in what airplane would Antonio Locatelli make good on his promise to conquer the Atlantic crossing for Italy?