Published on August 9, 2012

“To invent an airplane is nothing. To build one is something. But to fly is everything.” So spoke Ferdinand Ferber in a dedication to Otto Lilienthal, the greatest of the grandfathers of aviation. In three short sentences, Ferber captured the very essence of flight and what it means to be a pilot. Whereas others would make doodles on paper or muse in scientific literature, Otto Lilienthal’s life would follow those three lines perfectly — he would do more than doodle and dream, he would build and he would truly fly.

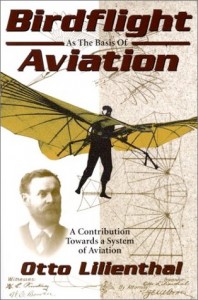

In his life, Otto Lilienthal would pioneer not only the art and science of piloting but also a new understanding of aerodynamics. His book, Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst would be published in 1889 (the English edition, entitled, Birdflight As The Basis of Aviation would finally be published in 1911). Its pages scientifically defined the matters of air flow, wing shape, how birds control direction and altitude. He profoundly understood and corrected scientific understanding of flight. He would write, “All flight is based upon producing air pressure, all flight energy consists in overcoming air pressure.” His carefully collected body of actual experiences and tests would serve to guide the way for the generations that followed — indeed, he lit the way to Kitty Hawk.

A Terrible Accident

Yet this day in aviation history marks a fateful one for Otto Lilienthal. On August 9, 1896, Lilienthal launched himself off a slope in the Rhinow Hills and fell from the skies to his death. His first three flights of the day were successful — one even reaching a distance of 250 meters before landing. Then, a fourth time, he hauled his glider up the hillside. Climbing into the apparatus, he readied himself and with a few short strides, hurled himself back into the air.

At first, the flight went well, but then Lilienthal pushed to steepen his attitude, hoping to extend his glide as he neared his touchdown point. Following rules of physics that Lilienthal himself had just started to understand, the glider’s forward speed slowed and, with Lilienthal pushing the nose higher, his wing stalled. The glider fell nose first toward the ground.

Lilienthal found himself at low altitude with the wing in a full stall. A fully developed stall was a new experience and he knew little of the aerodynamics of stall recovery. Predictably, he swung his body further backward in the glider to try and pull the nose back up. It was his final mistake. As any modern pilot can attest, this act will only worsen the stall. A proper stall recovery is counter intuitive — the pilot has to push the nose of the plane sharply down first to reestablish airflow over the top of the wing; then he can begin pulling up. This restores lift, allowing the pilot to recover from the dive safely — if he has enough altitude.

Lilienthal never stood a chance. He was but 15 meters high when his glider stalled, too low to land without injury and yet not high enough to recover from the stall. Even if he had pushed the nose forward, he would have likely crashed anyway. He hit the ground with extreme force and his glider collapsed around him in pieces.

After the Crash

Lilienthal’s glider mechanic, Paul Beylich, took the still-conscious pilot to nearby Stölln by horse drawn carriage. There he was examined by a physician who found that Lilienthal had fractured his third cervical vertebra. Lilienthal fell in and out unconsciousness as his condition worsened. He was transported on a freight train (the first available) to Berlin where the surgeon Ernst von Bergmann went to work trying to save his life. His brother Gustav arrived to assist, but Lilienthal could not be saved. On August 10th, Otto Lilienthal died from complications of the injury.

His final moments too would serve as a profound statement of the coming era of early aviation — legend has it that his brother Gustav overheard Otto’s last words — “Opfer müssen gebracht werden!” (Sacrifices must be made!). Whether or not he did indeed say that is uncertain but it probably doesn’t matter — that simple truth was understood by everyone who followed his experiments. In fact, those words echo a sad truth through all of aviation history. With every generation, sacrifices have been made in lives and fortunes to press the boundaries of knowledge outward.

Otto Lilienthal, the Glider King and Grandfather of Flight, would leave behind a legacy of work that would inspire countless others after his passing. He was, in every sense, the world’s first true pilot and one of history’s greatest aviation innovators.

Buy Lilienthal’s Book, Birdflight As The Basis of Aviation

One More Bit of Aviation History

Over the years, the design of gliders has come a long way from Lilienthal’s time. Whereas Lilienthal’s bird-shaped machines (some even featuring feathered appendages) would perhaps achieve a 3:1 glide ratio (3 feet forward for every foot down), modern high performance gliders typically feature glide ratios of 30:1 or even 50:1 or more. This allows pilots to set records that would amaze even Lilienthal. For instance, the British Gliding Team’s pilot, Kim Tipple of Lasham Airfield, UK, can fly his Nimbus 4t at speeds of over 120 km/h and over distances of greater than 500 kilometers at international racing events around the world. The New Zealanders Terry Delore and John Kokshoorn set the all time record of 2,501 kilometers flown in 2009 in an Ash 25 sailplane. Flying at approximately 28,000 feet most of the way, even if elated, however, Delore described the experience as “”Bloody freezing.” Click here to see the route of the flight.