Published August 8, 2012

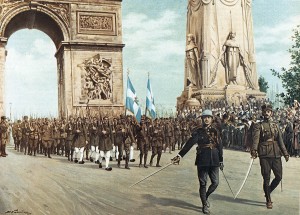

On this day in aviation history in 1919, the French public woke to read in the newspapers of Paris that a French aviator and veteran of World War I, Charles Godefroy, had flown under the arch of the Arc de Triomphe the previous day. What is even more stunning is that he didn’t do it for personal glory, but rather as a symbolic protest for all of the airman who had been required to march on foot earlier at the July 14th parade that marked the end of the Great War. No aerial armada had flown overhead during the parade, which the pilots considered a personal slight and a matter of honor. After a few drinks, the pilots decided that something had to be done…. What they would do would cost the life of a top scoring ace, make an amazing film (even if banned in France), and go down in history.

A few weeks prior to the July 14 parade, the Défilé de la Victoire (Parade de la Victoire), the French pilots had gathered at the Fouquet cafe bar on the Champs Élysées to discuss what they could do. After much discussion and a few too many drinks, they elected to stage a protest by flying a single airplane under the Arc du Triomphe during the parade. The honor would go to the senior most ace and pilot, Jean Navarre, who had 12 confirmed kills and an additional 15 unconfirmed claims. The pilots intuitively knew that the flight through the Arc would upstage the parade. Further, as no pilot had ever successfully flown under the arch, the act go down in history. It would be a fitting protest.

Disaster at Villacoublay

Disaster struck just four days before the parade on July 10th when Jean Navarre crashed and was killed while practicing low flying techniques over the airfield at Villacoublay in preparation for his parade flight. Undaunted, another of the pilots, Charles Godefroy, volunteered to fill in. Godefroy had impeccable flying skills and fully 500 hours of flight time, a very high number for pilots of that time. He had fought as an infantryman in the war and, after a serious injury, had recovered and joined the air force. His expertise in the cockpit was such that he became a flight instructor rather than having been assigned for front line flying. Yet even with a skilled pilot, the flight would be very dangerous. With just four days before the parade, Godefroy rescheduled — he would need to practice first.

After several trips to the Arc de Triomphe to work out the details and clearance, Godefroy selected a Nieuport Bébé for the flight. With its small wingspan of 7.52 meters, this would give him 7.25 meters clearance on each side (reasonable, but still a very narrow margin). Godefroy asked his friend, the journalist Jacques Mortane, to film the event. Together, they worked out the best approach path and the most dramatic sites for camera placement. Mortane elected to set out two motion picture camera to be sure that he caught the flight from both angles, going in and coming out. Godefroy then spent the next week practicing at a bridge over the Small Rhône at Miramas, not far from where he originally received his flight training.

The Daring Flight

Just after dawn on August 7th, fully three weeks after the parade march, Godefroy felt he was ready. He dressed in his best military uniform, climbed into the cockpit of a Nieuport Bébé, and took off from Villacoublay Aerodrome. He approached the Arc de Triomphe and circled it twice at low altitude, observing the winds and conditions. Then he descended and flew down the Avenue de la Grande-Armée before nosing over to less than 5 meters of altitude. The Nieuport had no throttle, and therefore as was common with early rotary engines, power was controlled by blipping the engine on and off. Godefroy headed for the narrow gap of the Arc with the engine roaring for maximum effect (this also minimized the relative effects of winds and turbulence).

In the final seconds of his approach, Godefroy passed extremely low over the top of a public tram on the avenue. In panic, the passengers threw themselves out onto the ground. Likewise, at the sight of the roaring Nieuport racing down the Avenue, pedestrians along the sides fled in terror. Then, in the blink of an eye, Godefroy had passed underneath. He pulled up to avoid the nearby trees and then buzzed the Place de la Concorde to celebrate his achievement.

His protest act completed, Godefroy returned to Villacoublay for a landing. Incredibly, nobody at the airfield had even noticed his absence. He had been gone just 30 minutes. His mechanic did a quick check of the engine, as one would do normally after a flight, and Godefroy simply walked away.

Aftermath

When the story broke the next day (August 8, 1919), authorities were livid. The military and political leaders were quick to react. Their primary fear was that other pilots would attempt to repeat Godefroy’s feat — they were wrong, of course, because once it had been done, few others felt it would be worth the risk. Jacques Mortane’s movie cameras both worked perfectly and he had the film of a lifetime, yet when he approached the theaters, authorities learned of the film’s existence. They banned its showing, fearing that it might incite others.

Godefroy attempted to keep his participation secret, but eventually, he was found out. Nonetheless, to avoid a public flogging and trial, authorities only issued him a warning. He received no disciplinary action. Even if he was never punished, Godefroy would give up on flying permanently. He returned to his wine business at Aubervilliers and lived out the remainder of his life in relative anonymity. Why give up flying? Maybe, as a pilot, you’d have to wonder what’s left to do? How you top that experience?

As for Jacques Mortane’s film, you can see it on YouTube.

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

It would be another 62 years before Alain Marchand would repeat the feat and fly under the Arc de Triomphe a second time in October 1981. Authorities were less accepting of his feat than they were of Godefroy’s flight. Marchand was fined 5,000 French francs as a penalty. Ten years later, in August 1991, the feat would be repeated yet a third time but in a stolen Mudry Cap B-10. The pilot would take off from the Aeroclub at Lognes, proceed to Paris, fly under the Arc de Triomphe and then continue on to fly under the lowest arch of the Eiffel Tower as well. Combined, both passes would go down in history — but was it worth the jail time?

Another great story about the time aviation was still at its romantic, albeit early stages of development. Congratulations on your excellent work!

This feat was also claimed by a fictious World War I flyer named Charles Veil in his book, 99 Lives, which was published in 1934. The stories in the book claim to be one man’s life but must be an amalgam of a number of different people. This is a shame as they really display adventures from a different era and if properly attributed would definitely astound today’s armchair travelers.

Hi Chris —

I have become intrigued by Charles Veil having read “99 Lives”. He was not fictitious and his war record is detailed in the history of Spad 150 — see link below. However, the account of the Arc flight isn’t!!

http://albindenis.free.fr/Site_escadrille/escadrille150.htm

I am trying to get to the truth if I can!! As an ex-Biplane pilot this is very interesting to me!

Best wishes,

Steve

I have some details regarding the preparation of Jean Navarre’s flight under the ‘Arc’ but need

some verification. Did he build a wooden framework and was he killed whilst practicing a flight

through this framework?