Published on October 16, 2012

On this date in aviation history, Samuel Cody took off in his British Army Aeroplane No. 1 at Farnborough, England, and set a second “first” in British aviation history — he crashed. His goal was to extend the distance achieved in his flight experiments. Just eleven days earlier, on October 5, 1908, he had made his first successful flight, a short “hop” with a successful landing. Now, as the plane raced forward, he lifted off and gently held it aloft as far as he could. The engine chugged and the propeller churned. Gently, he managed the controls and soon had extended the distance beyond anything previously achieved. He flew for 27 seconds and reached an altitude of 40 feet. Yet he crashed on landing after trying to turn too sharply when a cluster of trees blocked his flight. Cody walked away from the wreck. He had become not only the first to take off and fly a heavy-than-air powered aircraft in Britain but also the first in Britain to crash a successfully flying airplane.

Yet what many British don’t realize is that the first Briton to fly was actually an… American?

Samuel Cody’s Roots

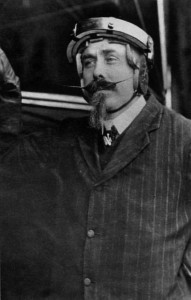

Samuel Franklin Cody was born Samuel Franklin Cowdery in Davenport, Iowa, on March 6, 1867. In early life, it is virtually without question that for a few years he lived the life of a cowboy on the trail. Based on that experience, which he also saddled up for the rest of his life as a core piece of his public persona, he elected to pursue the honored profession of circus showman. Soon, dressed as a rugged cowboy frontiersman, he was demonstrating his skills in shooting from horseback and lassoing for amazed crowds.

In 1888, he joined with Forepaugh’s Circus and toured the USA — he was just 21 years old at the time. A year later, he married a Pennsylvanian woman named Maud Maria Lee, who shared the circus stage under the name Lillian Cody and performed her own shooting act. The husband and wife team then toured England and Europe together and Cody penned a series of Western theatre acts. Sadly, while in London, Mrs. Cody suffered some sort of injury, which resulted in a morphine addiction that compounded with schizophrenia (though whether she had that true diagnosis is a matter of speculation given the state of psychology in that era). Ultimately, she returned alone to America. Quite possibly, she left as Samuel Cody had taken up with a London woman named Mrs. Elizabeth Mary King. After Mrs. Cody’s departure, Mrs. King and Samuel Cody moved in together and thereafter she was known as Mrs. Lela Marie Cody. As a result, Samuel Cody remained in England for the rest of his life.

Early Experiments with Flight

With the mind of a showman, one would never have suspected that Samuel Cody would become a pioneer British aviator. His interest in flight was no doubt kindled by the British balloonist Auguste Gaudron, with whom Cody performed his shooting tricks at the Alexandra Palace. Soon thereafter, Cody and his common law wife set about developing a series of military reconnaissance kites. Claiming to have been introduced to kites that lifted men for artillery spotting by a Chinese cook while riding the cowboy trails in America, Cody soon brought his kite concepts to the British War Office in December 1901.

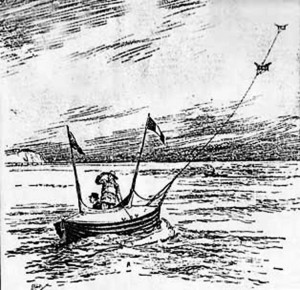

His patented design called for a series of box kites on a long tether to stream out in line at the bottom of which was attached a basket in which a man could stand and spot artillery missions for the military. He demonstrated his kites to an altitude of 2,000 feet and offered them for use in the Second Boer War. Lacking a military buyer, he demonstrated his kites at the Alexandra Palace in 1903 and thereafter became the first man to fly across the English Channel from Calais, France, to England, carried aloft by a kite towed behind a boat. His first attempt failed, but he tried again in November and this time to he didn’t quite make it and twice had to have his kite lashed to the mast for a bit before reascending but nonetheless the whole crossing was made this time. This landed him a contract with the Admiralty to evaluate the use of his man-carrying kites for observation when towed behind battleships.

Yet kites did not quite sate his appetite for flight and, emboldened the progress in America and continental Europe with gliders and aircraft, he developed a series of gliders based on his kite concepts, which successfully flew in 1905. By 1906, he was engaged by British Army and Royal Engineers as their Chief Instructor in Kiting. The story has it that amidst the posh and proper British Army soldiers, he would ride to the barracks on a white horse, his long hair and mustache setting him apart. The unit that he helped create evolved into the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers, No. 1 Company. In later years, this too would evolve into Briton’s famous No. 1 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps (later RAF No. 1 Squadron).

By 1907, he was hard at work with the British Army assisting in the design of the military’s first dirigible, Nulli Secundus. He served as the principal designer of the propulsion system and control car. On October 5, 1907, he and Col. J. E. Capper, British Army, flew the Nulli Secundus on its first flight, in which they orbited St. Paul’s Cathedral in a clear showing of the aircraft’s capabilities.

The First Flying Machine in Britain

As winter of 1907 approached, finally, Cody set his sights on designing a flying machine, the nation’s first powered heavier-than-air airplane, which became known as British Army Aeroplane No. 1. The machine had a 40 foot wingspan and was entirely Cody’s own design. A year later, in September 1908, he began testing the machine on the fields heading toward Cove Common. At first, he motored around in what today would be called taxi tests. Then, satisfied with the performance, he managed a short “hop” on October 5, 1908 — this is widely recognized as Britain’s first official flight of a heavier-than-air aeroplane.

On October 16, 1908, he would finally make a longer distance “hop”, covering 1,390 feet in Aeroplane No. 1, which culminated in a crash. Unharmed, Cody walked away from the wreck and soon thereafter in the Spring of 1909, in a bizarre twist, the British Military cancelled their flight programs and gave Cody his Aeroplane No. 1 at the end of the contract. A month afterward, on May 14, 1909, he set a distance record of over a mile in the aircraft. Proceeding on his own, he modified the aircraft to carry passengers and thereafter took Col. Capper up for a flight. Immediately thereafter, he also took his wife, Lela Cody aloft.

The End of Samuel Cody

His experiments won a string of awards and medals. He even flew at the famous 1909 meet in Britain, completing a lap before crashing, and at that event, he finally became a British citizen. He continued on and set numerous records and completed many tests in his aeroplanes culminating in him winning the 1912 British Military Aeroplane Competition on Salisbury Plain, in which he demonstrated the advantages of his Cody V aircraft with its 120 hp engine. He came away with a prize of £5,000, quite a bit of money in those days.

Over his nearly six years flying his aircraft — he designed at least five — he had numerous crashes, including one in which his engine cut out while at 2,000 feet of altitude. Shrewdly, he glided down to an emergency landing in a field. It would have all come out alright if he hadn’t hit a cow on landing (another first in Britain). He continued to work on his aircraft until August 7, 1913, when testing a new hydroplane of his own design called the Cody Floatplane, he was killed along with a passenger named William Evans (a famed cricket player), His aircraft broke up in mid-flight while at 500 feet of altitude and both men plunged to their deaths.

He was buried with full honors at Aldershot Military Cemetery. His coffin, draped in a Union Jack, was hauled on an artillery carriage by six coal-black horses lead by the Band and Pipers of the Black Watch Highland Regiment. The extraordinary spectacle of his funeral procession was attended by a crowd of approximately 100,000, who came to pay final respects to Britain’s first aviator, who just happened to be an American.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Samuel Cody’s artillery spotting kites finally won British Army approval during the Great War (World War I) with the artillery. A little known bit of history is that not all artillery spotting was done from airplanes and observation balloons. Cody’s kites, known as “Man-Lifter War Kites”, were employed on the front lines to loft men for the purposes of spotting enemy positions and directing artillery fire.

Today’s Aviation History Question

What happened to Samuel Cody’s wife, Mrs. Lela Cody, and his only son after his death?