Published on December 14, 2012

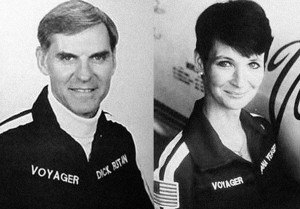

Sitting together over lunch, the three discussed how a plane could be designed and built with one purpose in mind — to fly around the world, non-stop, with no aerial refueling. It was a daunting task — many said it was the last great aviation achievement yet to be made — but for the three sitting around the table, it seemed doable. Two were brothers, Dick Rutan and Burt Rutan, and the third was Dick’s girlfriend, another pilot named Jeana Yeager. The year was 1981 and with little more than a restaurant napkin, Burt Rutan sketched out the essential design. The plane would have a thin, long wing (a high aspect ratio), included a central fuselage for the two pilots and twin engines, one on the nose and the other on the tail. It would be a twin-boom canard design with each of the booms terminating in a rudder. As the three left lunch, Burt pocketed the napkin and went to work. The dream had begun to take shape.

The Plane

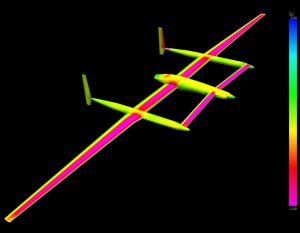

The plane would come to be known as the Voyager. It was optimized in every way possible — for 1980s technology, which was riding high on the home builder revolution that Burt Rutan had helped create with his Vari-Eze and Long-Eze designs. Carbon fiber, kevlar and fiberglass would be used to ensure the lightest, strongest airframe. The engines would off the shelf designs — a pair of Lycoming O-235s would be used for testing but replaced with a better engine choice for the flight itself. The final configuration used an air-cooled engine in the front, a Teledyne Continental O-240, and a water-cooled engine in the back, a Teledyne Continental IOL-200.

The plane wouldn’t be fast but it would be heavy. At best cruise, it was expected to fly at around 110 to 120 kts, yet on take-off, it weighed 9,694.5 pounds (4,397 kg). Of that, approximately 90 percent of the total weight was AvGas. Hopefully, it would be enough to fly the full circumference of the Earth.

The Flight

At 8:01 am on December 14, 1986 (today in aviation history), the Voyager took off from Edwards AFB. It made use of one of the longest runways in the world, fully 15,024 feet in length. Incredibly, the aircraft used all but 800 feet of the runway before finally lifting off. It was the first time that the plane had been fueled with a full load and so, the world flight was also something of a test flight. As it happened, with so much fuel weight within, the wings dragged on the runway as the plane accelerated, damaging both tips. With building speed, the wingtips lifted off and they were able to hold the runway perfectly as the plane slowly accelerated. Finally, as they neared take-off speed, the wings bent upward at an astonishing angle, stressing the wing spar, yet still, the plane lifted off gracefully and climbed out slowly.

Ahead lay a challenging course that would cross the equator twice, traverse more than 26,000 miles, and require at least nine days of flight to complete. The two, Jeana Yeager (no relation to Chuck Yeager, by the way) and Dick Rutan, planned to fly in three hour shifts. While one pilot flew, the other would lay down in the fuselage alongside to rest. It would be a hard journey, but they had practiced it. In one test flight, they had proven it possible and had gone over 11,000 miles.

Challenges En Route

The aircraft was fragile, however. Soon, they realized just how fragile it was with a full load. Weather had to be avoided as turbulence could potentially shear off the wings. A spin or sudden dive would likely exceed the design speed limitations of the airframe. With a full load, the stall speed was very high — quite near the cruise speed — so a pitch up would cause a stall and a spin. There were no spin tests to prove the airplane and it was simply recognized that if the plane did stall and spin, it would likely breakup in flight. One benefit of a canard configuration, however, is that the front elevator and horizontal stabilizer can be designed to stall just before the main wing — thus, a stall would be more like a mushing forward and down. It could spin, however, though it was probably manageable.

As expected, there were problems. Weather problems emerged off the coast of Brazil as storms buffeted the plane, an experience that would be repeated over Africa, threatening the fragile aircraft. Navigational issues arose when they were denied overflight clearance at the last minute for the portion of the flight transiting Libya. Muammar Qaddafi wanted nothing to do with the “spy plane” as he saw it. As well, crossing the Pacific, they had to deviate over 600 miles around Typhoon Marge — it was unexpected and add nearly six hours to their intended flight duration. Pilot fatigue soon become a serious issue. With the difficulties of flying it with a high fuel load, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager couldn’t change pilots as often as the planned three hours.

As they neared the destination, just a few hours from Edwards AFB, they had a catastrophic engine shut down. As the plane spiraled slowly down under control, Dick Rutan was able to get the front engine restarted. With that, he limped upward as he worked on restarting the back engine as well, which had an oil problem and a failing water pump. It too restarted — somehow — and they continued on. Finally, the fuel pump on one side failed as the plane neared California — they cross-fed the engine to keep it running. A chase plane joined up — a Beech Duchess — and flew with them the rest of the way. Then the welcome sight of Edwards AFB loomed into view.

Landing and into History

Finally, 9 days, 3 minutes and 44 seconds after departure, the Voyager touched down safely. They had done it. In the fuel tanks were just 106 pounds of remaining fuel — about 17 gallons, not all of it usable. It had been a very close run affair. In the end, the project that had begun on the back of a napkin had taken shape over 5 years, involved 99 volunteers and nearly all private donations — just a handful of companies offered sponsorship. Far from a slapdash effort, the “napkin” had transformed to draw in the very best aeronautical engineering talent, knowledge and systems in the world. Not a dime of US Government funding was used. It was a private, civilian venture — one might even say “amateur” affair — though none of those involved were anything less than the best experts required to make the flight possible.

To this date, the Voyager remains one of only two planes to have circumvented the globe fully, crossing the equator twice to meet the core requirement. To recognize the achievement, the pilots and the designer received the Collier Trophy as well as recognition from none less than President Ronald Reagan himself, who bestowed on them Presidential Citizens Medal, the second highest civilian award in the USA.

One More Bit of Aviation History

The design work that went into the Voyager was not the usual hand drawn, wind tunnel tested configurations that until then had largely been the standard in aviation. Rather, the Voyager was optimized with a virtual, computerized wind tunnel testing process — a software solution called VSAERO. Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), VSAERO can not only cut costs in development but also provides aeronautical engineers with unprecedented capabilities in testing options, different configurations and different angles for everything from fairings to airfoils.

In the USA today, there are a handful of firms that are truly specialists with VSAERO, including one that is run by one of the engineers who helped work on the Voyager all those years ago — Aeromechanical Solutions LLC (AMS), where high end aerodynamic engineering projects are performed by a University of Michigan graduate and visionary engineer named David Lednicer.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What other aircraft has completed a full global circumnavigation of the Earth with two crossings of the equator?

B-52?

The Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer, from February 28, 2005, until March 3, 2005. The aircraft was designed by “Voyager’s” Burt Rutan.