Published on February 23, 2013

One hundred years ago today in aviation history, on February 23, 1913, the Bristol Scout racing plane made its first flight at the hands of one of its two designers, Harry Busteed. The other designer, Frank Barnwell, witnessed the flight and knew that they had designed a superb machine. While the Scout was originally conceived as an air racer, it was quickly picked up by the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Navy as an ideal light, single seat observation aircraft. Fast and with excellent lines, it would serve well into the Great War. Yet what made the Bristol Scout truly special was another first — it was the first parasitic fighter, carried aloft attached to the top of the wing of another airplane. When having been flown far away and well beyond its normal range, the concept of the Parasitic Fighter was that the airplane would start its engine, detach itself and enter combat.

The goal of the Bristol Scout Parasitic Fighter? To intercept German Zeppelins heading for London not long after they took off from Germany and before they had climbed out of reach.

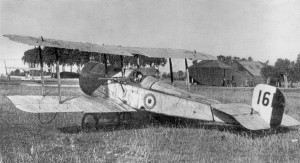

The Bristol Scout Design

The design of the Bristol Scout included many innovative aerodynamic features. Among the most interesting was the rudder which, like the Morane, Nieuport and Fokkers of the day, had no fixed vertical stabilizer, so that the entire rudder rotated on a center post. The main landing gear were narrow so as to reduce profile drag, being just slightly wider than the narrow fuselage, itself dictated by the exact measurement of the width of the 80 hp Gnome Lambda rotary engine. The engine too was enclosed in a tight cowling that almost completely encircled the cylinders and closed around the prop hub — just a small gap at the bottom allowed for air cooling. Finally, the wings sported a dihedral angle of just 1.5 degrees.

The result was a fast, nimble plane that more than met the British military’s requirements. By 1914, the RFC had acquired a number of the type and early experimentation was underway regarding armament. One idea was to mount two rifles astride the cockpit, both canted off to opposite sides so as to fire outside the arc of the propeller. The idea was that the pilot could close tightly with his enemy, but maneuver to a position offset to the side. Then, using the side-mounted rifles, he fire a rifle round to shoot down the plane by killing the pilot or hitting the engine. Needless to say, compared to the forward mounted machine guns that were being evolved by Garros and later Fokker with his famous interrupter gear, this proved less than optimal. The famed British aviator, Lanoe Hawker, dropped the rifles and instead mounted a Lewis machine gun at the same offset angle, though with a different mounting of his own design. That worked much better and he was able to down two enemy aircraft from his Bristol Scout, for which he was subsequently awarded the Victoria’s Cross.

The Parasitic Fighter Concept

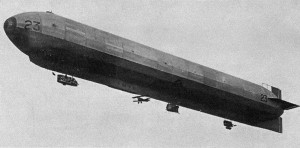

Above all, however, was the extraordinary innovation of the Bristol Scout as a parasitic fighter. The plane was mounted atop the upper wing of a Felixstowe Porte Baby reconnaissance flying boat. The Porte Baby was slow, in fact, a rather lumbering design, but it made up for its slowness with an incredibly efficient wing design that allowed it to carry immense weights for its day. At the time, German Zeppelins were attacking London, arriving in the midst of the night to surprise British air defenses. Dropping bombs from high altitude, the Zeppelins were the world’s first strategic bombers. Using ever high flying designs and pioneering all-weather flight and bombing methods, the Zeppelins were seen as a great terror weapon by 1916. Something had to be done and, as unexpected as it sounded, the parasitic fighter concept was born.

First, the thought was to mount a Royal Navy fighter to the underside of a British airship. The idea had merit since the airship could fly south far across the water toward Germany in the early evening, coinciding with the departure of a Zeppelin raid on London. Once off the German coast, the fighter would be dropped from the airship to intercept the great German airships not long after take off while they were still climbing for altitude, far from the shores of England. British fighters of that era lacked the range to fly that far and make the interception and return — and thus, the idea of transporting to the launch point under an airship was ideal as a fuel saving strategy.

The fighter could be launched, attack the Zeppelins early in their flight and then fly back to England — which was within one way range. Sadly, however, the airship launch method did not work out — put simply, the airship’s forward speed was limited and the first tests resulted in an accident when the fighter dropped away in a stall and plunged vertically into the ground.

The Bristol Scout Parasitic Fighter

It would be Commander John Cyril Porte, who headed up the Royal Naval Air Station at Felixstowe who had the solution. His idea was to mount a Bristol Scout C atop an aircraft he had designed, called the Felixstowe F.1, but more commonly known as the “Porte Baby”. The Porte Baby’s top speed was just a little more than 85 mph, but it cruised at about 10 to 15 mph slower than that. This was certainly sufficient speed for the Bristol Scout to fly. The major challenge would prove to be the release and separation of the two aircraft.

By late 1915, Commander Porte was experimenting with various mounting and release mechanisms. His ideal solution was a pair of slots for the two wheels of the Bristol Scout, two hooks that held the front axle and a central hook to hold the plane’s tail in place until it was ready to fly off. For the first test, Commander Porte himself undertook the flight, but not in the Bristol Scout, rather in his Porte Baby. The apparatus was described in the Royal Aero Club’s publication, Flight, in a later issue (1937), recalling the design used:

The Bristol Scout was secured in its housing on the top centre section by a pair of crooks over the axle, the wheels resting in a shallow trough; a quick-release hook was attached to the rear end of the fuselage. For the test the weight of both the flying boat and the aeroplane was kept as low as possible, little military load and fuel being carried.

All looked promising, but the experiment nearly ended in disaster as when the hook was released and rear hook malfunctioned, holding the tail of the plane fast to the top of the Porte Baby. Based on the aerodynamics, the Bristol Scout with Flt. Lt. M. J. Day, RN, at the controls, twisted in place and shredded a portion of the Porte Baby’s top wing. Commander Porte was able to get both planes back on the ground, still connected, but it was a close call. A redesign of the release mechanism was needed so as to reduce the potential for yaw effects fouling the separation.

Finally, on May 16, 1916, the first success was achieved and the Bristol Scout was able to simply separate, with the pilot pulling back gently on the stick to lift away vertically from the top wing. Once sufficiently distant, he turned out and safely flew clear of the Porte Baby. It worked perfectly and became the first successful aerial test of a parasitic fighter in history. Again, Flight described the success in detail — which took place in Felixstowe Harbour:

The engine of the Bristol was started just prior to the boat turning into wind and was kept running as slowly as possible by “blipping” the switch. The Porte “Baby” got off the water in about the usual run and slowly climbed. Day then ran his engine full bore, and at a height of under a thousand feet the tail release was slipped. After a slight momentary drop the Bristol climbed slowly and landed at Martlesham Heath.

After this one flight, the tests were never repeated and the parasitic fighter was never used in its originally envisaged role of intercepting Zeppelins. The key problem was that the Porte Baby’s slow speed made it a easy target for enemy German fighters that might be patrolling near the coastline of Germany. In fact, at the time one Porte Baby (not a parasitic carrier) was intercepted while off the coast of Holland and badly damaged. It landed in the English Channel and taxied all the way back to the English coast under its own power — ah, the glories of a flying boat! After that, the British restricted the use of Porte Babys to coastal regions out of range from German fighters. The parasitic fighter concept was shelved.

Above all, the Bristol Scout proved to be a versatile, excellent fighter and observation aircraft. Its racing design carried it through operations that spanned more than half of the four and half period of the Great War. Having proved parasitic flight, it opened an entirely new field of aerodynamics — one that would be picked up by numerous air forces around the world. Finally, it was one of the early and most innovative fighter scouts in aviation history, helping to pioneer the new field of aerial combat. Who would have thought that a pre-war observation plane would prove so influential over the years?

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Name five famous aircraft that were launched either as parasitic fighters or as experimental test planes.