Published on April 21, 2013

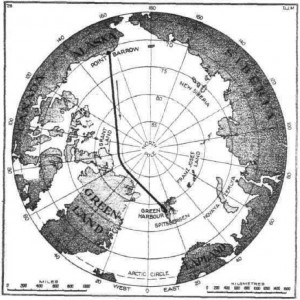

The news reports carried word of a flight across the Arctic that had departed nearly a week earlier, on April 15 and 16, 1928. Five days after departure, still the flyers were not yet safe. As the day broke on April 21, 1928 — today in aviation history — the men, who had been forced down on the ice amidst worsening weather, made a go of it. After nearly not getting off, they flew out and shortly afterward arrived at Spitsbergen. Their flight had connected Point Barrow, Alaska, with the northern island of Norway. The two men, an Australian named Hubert Wilkins and an American named Carl Ben Eielson were skilled Arctic voyagers and so, despite the challenge, they had fared well. Still, their first message out was confusing, as relayed through Svalbard to the flight’s sponsors, it had read:

Traversed course outlines one. Account bad weather. Arrived 20 1/2 hours. Flying time, five days from Barrow. No foxes seen.

Foxes in the Arctic? A lot of people wondered at that. Yet the flight had been the first to traverse the Arctic, traversing 2,200 miles of ice, and that was amazing enough, with or without any “foxes”.

The Daring Flyers

Capt. Hubert Wilkins and Lt. Carl Ben Eielson were two former military officers. The first, an Australian, was a privately trained pilot from 1910 who was also veteran of the combats at Ypres. The latter was American a pilot from the US Army Air Corps who hadn’t finished training when the Great War ended in November 1918. Both were experienced in cold weather flying and Arctic expeditions. Eielson, born of Norwegian parents who had settled in North Dakota, had been the first man to fly the air mail in Alaska, shortening a 20 day dogsled delivery route to four hours of flight time. That was something of a local revolution as it also meant that for the first time many inland towns and villages were connected to the rest of Alaska by faster, easier and more affordable means.

Likewise, Hubert Wilkins was a proven Arctic expedition photographer and veteran of many journeys to the frozen north. Critically, he had helped pioneer the art of aerial photography, working with Gaumont Studios and having made his first trip into the farthest reaches of the north in 1913 with the Vilhjalmur Stefansson Canadian Arctic Expedition. As well, he had participated on the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition of 1921–22, charting Antarctica with Sir Ernest Shackleton — that voyage was the last such journey by the great man himself.

Searching for Graham Land

The goal of their flight from Point Barrow to Spitsbergen was to search for a previously uncharted land that was rumored to exist somewhere in the Arctic, perhaps near the North Pole. This was the so-called “Graham Land”. Tales told of a land of snow and mountains, though many were concerned that if such mountains had existed, surely one of the previous Arctic expeditions would have spotted them looming in the distance. Such a land could exist, others reasoned, but if it did, it would have to be flat and with only low hills. From the air, it would be easy to make out such features, many felt, as the break up of the ice along the Arctic Shelf would reveal rocky shores. Windswept hills could be pinpointed by the black rocks that would stick through the snow drifts. If Graham Land were to be found, it would be best done by air.

To make the flight, the two men used a Lockheed Vega with a 220 hp Wright Whirlwind engine. The Vega was an established record-setter with excellent reliability. It also featured an enclosed cabin, an important aspect for flights over the far northern reaches of the Arctic. Inside the high wing monoplane, the fuselage was large enough to carry the two men, plus emergency supplies and gear, as well as enough fuel in main tanks to fly nearly a day without stopping.

The Perilous Flight

On April 16, 1928, using a newly prepared airstrip, the two men departed Point Barrow, Alaska. They took off into a headwind on an airstrip cleared by local Eskimos. A week earlier, they had used a different airstrip, but suffered a broken ski while trying to get off in a crosswind. With repairs made, this time they got off well. The weather was good and they were hoping to enjoy the Arctic Springtime, expecting that it would help them avoid storms. Their plan was not a direct flight across the North Pole, but rather to edge around to the right, farther south, and thereby navigate through what was then known as the “Blind Spot of the Arctic”, a region that had been previously unexplored. If Graham Land existed, the best chance for it — maybe even the last chance — would be there.

Once airborne, hour after hour, the men droned along in the Lockheed Vega. As they flew, they scanned the distance to both sides of the plane in hopes of spotting some outcrop or rocky protrusion. For navigation, given that the magnetic variation would leave their regular compass too inaccurate, they relied on sun shots that they would take with an RAF issue Mk. V bubble sextant. They flew at 6,000 feet to ensure that they had good visibility, yet not too high to miss anything. About ten hours into the flight, they were approximately 300 miles south of the North Pole. At about thirteen hours into the journey, they spotted their first mountains. Yet these were not the hoped for Graham Land, but rather the mountains they saw out to the right of the plane were to the south, in the distance and exactly where they knew them to be. These were the northernmost mountains of Greenland.

Bad Weather Closes In

At that point, they had flown approximately 1,200 miles straight across the “Blind Spot”. Thehey had not seen anything except water, icebergs and the ice shelf. At that point, their exploratory work was essentially done. The remaining 1,000 miles to Spitsbergen were the well-charted waters north of Greenland, north of Iceland and north of Ireland and Scotland. They continued on, hoping to land at Spitsbergen as planned, which was then about 8 hours distant. The weather, however, steadily worsened as they flew on. Finally, just short of their goal, they could go no further. The plane was flying through a raging blizzard. They were close to Green Harbor, but it didn’t matter, they would have to put down on one of the islands nearby.

They found one, then lost it in the low visibility, then found it again. Amidst the blizzard, Eielson managed a perfect landing — the winds were so strong that the plane stopped in just 30 feet. Quickly, Eielson drained the oil before it could freeze inside the engine — a lesson he had learned from his time flying in Alaska. They hoped to wait a day or so before continuing on. It didn’t work out that way, however.

For the next five days, amidst winds, blowing snow and storms, they sheltered with the plane, which they had tied down securely. Ominously, they later found out the small island that they had been on was name, “Dead Man’s Island”. They were well-equipped for the conditions, however, and did not suffer too badly. Both men were, after all, veterans of the Arctic. Finally, on April 21, the weather lightened up somewhat, permitting a take off. All they could do was hope that they would make it. It seemed that if they didn’t try, they might be there for many days longer as the weather seemed unpredictably dangerous. They were always cognizant that a bad gust could damage the plane, forcing them to try to hike out.

As it happened, they took off with some difficulty, the plane having a hard time getting airborne in the drifting snow, but soon they navigated their way to Spitsbergen. The landing at Green Harbor was uneventful and the two men, exhausted from the ordeal, dismounted from the Lockheed Vega for some well-earned rest — and a bit of warming up by the fire.

Aftermath

Over the next few days, word of their exploration by air made it out. Early headlines screamed of the adventure, a flight that connected Alaska and Norway over the Arctic, how the flyers had been forced down for five days en route. Later articles, such as the one that ran in Flight on April 26, 1928, carried details of the search for Graham Land and their experiences in the flight itself. The Royal Geographic Society’s chairman, Sir Charles Close, sent a congratulatory message to the two men — after all, Hubert Wilkins was a member of the Society. It read:

The Council of the Royal Geographical Society warmly congratulate you and Eielson on the remarkable feat of navigation and airmanship over the unexplored Arctic.

As for the “foxes”, it was later revealed to have been code to convey a secretive message to the sponsors of the journey. Had the men reported seeing “black foxes”, the sponsors were to know that Graham Land had been found and charted as a mountainous island. Had they reported instead, “blue foxes”, that would have meant that the land had been spotted and that it was flat or featuring just low hills. As it was, the message, “no foxes”, brought a finality to the journey of discovery. Though disappointed, the sponsors of the flight from the American Geographical Society came away knowing that they had resolved at least one of the mysteries of the Arctic — Graham Land was a myth.

From the Archives

The Fate of the Örnen — read about another aviation exploration to the Arctic, undertaken by balloon in 1897. Unlike the flight of Wilkins and Eielson, this earlier voyage of discovery did not turn out as well.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Carl Ben Eielson’s name has been honored by the US Air Force — in what way?

Eielson AFB was established in 1943 as Mile 26 Satellite Field. It is named in honor of polar pilot Carl Ben Eielson. The 354 FW is currently commanded by Brigadier General Mark D. Kelly.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eielson_Air_Force_Base