Published on April 20, 2013

It was ninety-nine years ago that the second Schneider Cup seaplane races were held off the shores of Monaco. The year before, Marcel Prévost had won in a Deperdussin monoplane. In 1914, England wasn’t considered much of a contender, as European aircraft manufacturers were viewed by most to be far superior in their design and manufacturing expertise. Yet Thomas Sopwith had a new airplane, the Sopwith Tabloid. A land plane, it put in times that were competitive with the best there was — in fact, it bested the rather slow, winning average speed of 61 mph put in by the Prévost when he had won the year before. The new Sopwith’s potential was obvious. With a more powerful engine and the addition of floats, it could be a contender. Hoping to give the plane the boost it needed, Thomas Sopwith went to Paris and returned with a 100 hp engine to mount on the plane, replacing its existing one of 80 hp. A float system was designed as well. The fast land plane became, in a snap, a seaplane racer. Yet could the race be won against the fastest planes of Continental Europe?

Testing and Last Minutes Changes

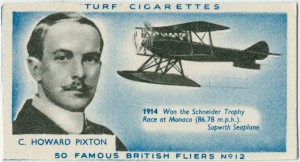

We just weeks left before the race the modified Sopwith Tabloid seaplane racer was put into the water (a river) for its first test flights. C. Howard Pixton was to be the test pilot, even if he was just getting over a virus that had kept him abed for some time. He mounted the plane, lodged himself into the cockpit and waited as it was pushed into the water. The engine was started and the Tabloid was turned toward the sea so that he could begin the takeoff run. As soon as the throttle was advanced, however, the aircraft simply flipped over onto its side from the torque, summarily ejecting Pixton out of the cockpit and into the water. Although he was rescued quickly, the plane remained adrift in the river until the following morning when a rope could be attached. It was dragged to the shore, heavily damaged and waterlogged. A major rebuild would be required, with time lacking. As well a different set of floats, more stable than the existing single, wide center float, would have to be crafted.

Back at the Sopwith works, the engineers and mechanics labored hard to get the seaplane back into shape and ready for the races. They were able to repair the water damage but no time remained to redesign and manufacture another float system. An innovative solution was decided on — really the only option — and the existing wide center float was simply sawed in half and mounted as a pair. A tail tip float was added to help ensure stability on the water. The next time the engine was run-up the plane wouldn’t flip over again. Only briefly tested in a run at Glovers Island, the plane was then packed onto a ship for a quick voyage down to Monaco, arriving just days before the race.

Thomas Sopwith took no chances, accompanying the plane with his expert mechanic,Victor Mahl, to ensure that the engine was tuned perfectly for the race. As in the test flights, the pilot was to be Howard Pixton. The team was ready, even if their plane was still an uncertain gamble.

Drama Before the Race

On arrival in Monaco, the team discovered that the competition had come in force. Three Nieuport monoplanes had arrived — two flown by the Frenchmen, Gabriel Espanet and Pierre Levasseur, and one by an American named C. T. Weymann. There was a Deperdussin flown by another American named Thaw, and an Franco-British Aviation (F.B.A.) Flying Boat flown by a Swiss pilot named Ernst Burri. Roland Garros and Lord John Carbery arrived with Morane-Saulnier machines. Finally, a German pilot named Victor Stöffler rounded out the pack.

The day before the race, both the German pilot and Lord Carbery wrecked their machines while testing. All was not well with the Sopwith Tabloid either, however, as it was found that the plane’s propeller was too shallow in pitch, resulting in the engine over-revving. A hurried change was effected and a new propeller with a smaller diameter and coarser pitch was mounted. This solved the problem of the over-revving but left the team uncertain as to what the actual performance of the plane would be the following day on the race course.

The Schneider Cup Race

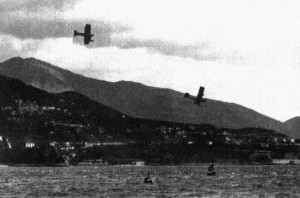

On race day, April 20, 1914 — today in aviation history — the planes took off one by one. The Schneider Cup wasn’t a race in the traditional sense of the word but rather a set of time trials where the planes would do their best to finish in the shortest amount of time over a long course. In 1914, this involved a 28 lap course, with each lap being 10 km long. It wasn’t a straight course either or a triangle of bouys, rather there were multiple turns. The shortest leg was just 260 yards long and the longest was about 3 1/2 km. The tightest turn was at Cap Martin which reversed the racers’ course by 165°. To prove the seaworthiness of the aircraft, every racer had to land on the water twice during the first lap.

Levasseur and Espanet were first off at 8:00 am — the very minute the official race began. They put up their best single lap times of 9 minutes, 17 seconds and 8 minutes, 55 3/5 seconds, respectively. The Swiss pilot Ernst Burri followed in the F.B.A., though he had trouble getting off the water. He logged a respectable 6 minutes, 17 4/5 seconds in his best lap, setting the time to beat.

Pixton was next in the Sopwith Tabloid. With the newly mounted coarser pitch prop, he was off the water in only 60 feet. Even with the two compulsory landings in the first lap, he logged an incredible 4 minutes, 27 3/5 seconds. The other pilots waiting to start were stunned. As the laps ticked by, the two Frenchmen and the Swiss watched as the Sopwith Tabloid overtook them and sped off ahead. Lap after lap, they realized that Pixton had the better plane, yet they soldiered on, hoping that his engine wouldn’t hold out — in 1914, engine failures were common, particularly at races, where the tuning was at the highest and the throttle was left wide open.

As it happened, it wasn’t the Sopwith that had an engine failure. Neither Espanet or Levasseur finished the mandated 28 laps. Many of the other pilots that had been waiting to fly, simply threw in the towel, recognizing as the hours went by and the laps steadily mounted that the Sopwith Tabloid was just too fast. Only Burri put up a full 28 laps. His time was 3 hours, 24 minutes and 12 seconds. Pixton in his Sopwith Tabloid finished an hour earlier with a complete course time of 2 hours, 9 minutes and 10 seconds, even though he flew two extra laps for total of 300 km! His average speed was 92 mph — it wasn’t just a race-winning time but also a new world record.

Aftermath

Whereas before the race France had been considered the best aircraft manufacturer in the world, with the Sopwith Tabloid’s world record speed and performance, Europe was forced to recognize that the underdog aviators and manufacturers of Britain had finally caught up. In a single day of competition, England had proven to Europe that it was their equal — and more. Just a few short months later, on July 28, the Great War would break out, involving all of Europe in a world war. As the four years of war that followed would show, Sopwith and his designs would prove themselves to be equal with the best there was. As history would soon demonstrate the Schneider Cup victory of 1914 was only the beginning.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

C. Howard Pixton was the race winner at the Schneider Cup of 1914 — what became of him thereafter?

Howard was commissioned a Captain in the RFC and joined the Air Investigation Department at Farnborough. After he war he worked with A.V. Roe and retired to the Isle of Man in 1932. During WWII he returned to the Air Investigation Department.

He was active in developing aviation at the Isle of Man such as flying newspapers and passengers to the Isle.

He died in 1972.