Published on April 24, 2013

At the end of the war, the US Army Air Forces made surplus a wide range of aircraft. Among the most prominent were the Douglas C-47 Dakotas, military versions of the Douglas DC-3 airliner, a proven aircraft for commercial air passenger transport from before the war. As thousands were retired from the military, they became the backbone of virtually every airline in the USA and even many overseas. In addition, they formed the foundation of a hot start-up sector which took advantage of the tens of thousands of former military pilots who were entering civilian life and looking for jobs. In the rough and tumble times that immediately followed the war, one operator based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, emerged with perhaps the most radical idea for a new service — to employ not only C-47s but also military surplus gliders to carry freight when towed behind their regular airliners, which ideally would carry ticketed passengers in scheduled and chartered service.

Thus, today in aviation history, on April 24, 1946, Winged Cargo Inc. made its first flight. This is their story — an innovative strategy for improving competitiveness in a crowded field of new airline start ups that had its ups and, after a short while, its downs as well.

First Flight and Start Up

Wing Cargo’s first flight was from Philadelphia to Miami, Florida, took place on April 24, 1946. After stopping there for a day of rest, the flight continued on to Havana, Cuba, to deliver its first cargo loads. The arline’s C-47 had been converted to seat passengers, but for this first flight carried none, only taking in tow one of cargo gliders that was packed with 7,500 pounds of freight. The operation required pilots in the C-47 “towships” and glider pilots in the CG-4A gliders who would keep the glider steady during the two, then be ready to drop off their tow line when they arrived over the destination airfield — or even farm field! Ideally, this allowed the airline to deliver the cargo to a rural destination en route while the airliner continued on to drop off its passengers at a major airport elsewhere. Together, as projected by the airline’s owners, the combined revenue from the freight operations and passenger ticket sales would make Winged Cargo a profitable and highly competitive venture.

The airline’s president and founder was Col. Fred P. Dollenberg, USAAF (Ret.), a former USAAF hero from the China-Burma-India theatre (CBI) and an ace with 17 kills (Japanese Zero fighters credited as downed by gunners on his plane) and five ships sunk during the war. For the airline’s first flight, Col. Dollenberg personally flew one of the airline’s three C-47s and glider combos. Behind was towed a converted US Army Waco CG-4A cargo glider. On board the plane as Col. Dollenberg’s crew were James B. Gleason, who was one of the directors and shareholders of the operation, and S. G. Friedman, who was the brother of Winged Cargo’s Puerto Rico based company representative. On the glider, two others were employed — John J. Martin and Paul M. Augin, both former Army pilots who had flown combat glider operations during the war in Europe. The company predicted that Puerto Rico would become a major destination and aimed primarily to serve the east coast of the USA, connecting to the islands of the Caribbean.

Others involved in the airline that day, but not flying, were a key investor (and former glider pilot), Raymond W. Baldwin, Jr., and Ray Hoersch, a former glider pilot who had served in Operation Market Garden, and was also commander of Wing 12 of the National WWII Glider Pilots Association, as well as Johnny Martin, who served as the airline’s chief glider pilot. Another at the top of the organization was Col. John Sheridan, a former congressman (D-PA) from Philadelphia who had later served with Gen. Carl A. Spaatz. At Winged Cargo Inc., Sheridan helped launch the operation and served as its chairman of the board and general counsel.

Meanwhile, a second C-47 took off with the glider in tow to pick up a load of canned soups for delivery from the factory to a faraway distributor. As Col. Dollenberg told the press during his layover in Miami, “The real future for commercial gliders lies in short hops of 400 to 500 miles.” He also predicted that the future for towship-glider operations would “great.”

Record Setting Flights

Winged Cargo would soon prove the capabilities of their gliders, making a record-setting 900 mile over water tow that started in Puerto Rico and spanned the Caribbean to Nassau in the Bahamas. From there, they flew directly up the east coast of the USA to Newark, New Jersey, where they delivered their cargo. It appeared that glider towing operations brought advantages in both weight carrying capacity and cubic size of the cargo loads, in large part due to the fact that another set of wings (on the glider) added considerable lift for heavier loads.

In another record-setting flight, Col. Dollenberg and Johnny Martin flew a load of cargo from Philadelphia to Georgia, dropped off the glider, landed, packed in another load, and took back off to return to Reading, Pennsylvania. There, they dropped off the second cargo load of the day — tomato plants, which were “in the ground before dark”, thus demonstrating the validity of glider freight operations to serve rural and farming needs. In a single day, from morning to night, they had flown 1,600 miles. In the first months of the operation, despite the hope to carry passengers, only cargo was moved in the gliders. By the end of the year, however, they had launched the passenger charter service, hoping to add scheduled flights and regular ticket sales thereafter.

So What Happened?

Things came crashing down — quite literally — when on December 16, 1946, after just eight months of operations, one of the company’s C-47s disappeared when en route from Kingston, Jamaica, to San José, Costa Rica. The plane, a C-47A-15-DL with registration number N88876, was carrying two crew and five passengers — apparently Jamaican farm workers as the company had landed a contract to transport labor throughout the region by air at the time, thus entering the passenger transportation market as planned. No glider was in tow when the crash happened.

In the wake of the crash, one of the largest search and rescue operations ever mounted in the region was mobilized, including assets from the Army, Navy and USCG. After three days, however, the search had turned up no sign of the plane. A rumor had it that the plane had come down in the jungles in Costa Rica, but that was later disproved. Ultimately, the plane and the passengers were never found. All were presumed to have been killed in the crash. Exactly what happened to the plane remains a mystery to this very day.

After that, the airline soldiered on for some months. By mid-1947, it was flying mainly passenger operations — many of which were flown by Col. Dollenberg himself, who had a propensity for bringing his three year old son, Eric, on flights. For the remainder of 1947, there are few news reports to be found concerning the airline or any further glider-based cargo flights. With dwindling revenues and suffering from the loss of one of its three C-47s, the airline was on the rocks. In November 1947, the Aeronautics Board filed action against the airline, seeking to halt its operations before operations became unsafe. Finally, in December 1947, with support of the courts, the CAB issued an order to the airline to cease all commercial passenger flights, which spelled the end of the company.

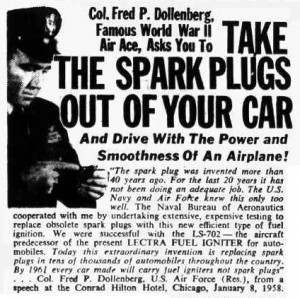

Col. Dollenberg moved on to form U.S. Igniter Corporation, and when that went bankrupt, later he founded a similar venture called Lectra, Inc. Both were manufacturers of fuel igniters for automobiles, which remained his business for the next nearly two decades. Though his company made claim to have the ideal replacement for spark plugs in automobiles, the marketing hype apparently didn’t match the performance of the product. A series of lawsuits followed, including from investors and shareholders. In May of 1965, Fred Dollenberg, at just age 49, would succumb to cancer — it was a sad end to a visionary airline founder and World War II hero.

As a point of interest, in the years following WWII the US Gov’t was selling surplus CG-4 gliders for $75.00 each. These gliders were NOT war weary or used A/C but were still in their original wooden packing crates direct from one of the dozen factories that produced the CG-4’s.

Interestingly, people did indeed buy them but NOT for the glider BUT for the box they came in!! Typically what would happen is that several neighbors would go together to buy a glider and have it delivered to someone’s home. The glider was then extracted from the end of the box and hauled off to the city dump. The various contributing neighbors would cut off a section of the box and take it home as it it made a great tool shed, play house for the kids, ham radio shack, etc.

Original cost of the CG-4: $ 15,000.

John Voss, thanks for reminding me of the story of the boxes that I heard from my father.

My Father, Charles W. Clements, Sr., and Paul DuPont hold an obscure aviation record when my father towed Paul from Miami to Cuba in the 1930s.

Winged Cargo sounds at first like a dumb idea unless you knew the gliders were disposable, retrieving them from these remote locations would have been a nightmare. Thanks for making that point.

The wreckage of the missing Winged Cargo C47 plane was found in South America around 1948

Los restos fueron encontrados en Costa Rica, conozco el lugar y aun existe parte del avión.

The remains were found in Costa Rica, I know the place and part of the plane still exists there.