January 19, 2021

By Thomas Van Hare

At the start of the Great War in 1914, Europe held sway over much of China. Great Britain had Hong Kong. The US and Britain jointly controlled Shanghai. The Portuguese had Macau. In all, 89 cities in China were controlled by various European nations at the time. These were ruled through a series of one-sided treaty agreements that, while they greatly benefited the West, also severely disadvantaged the Chinese. The Germans had sway over the port city of Tsingtao, also known as Qingdao, which was in Shandong Province directly on the Yellow Sea, roughly straight across west from Seoul in Korea.

Within days of the start of the Great War, the allied nations, including Japan, set their sights on uprooting Germany from its Far East holdings. The Japanese moved quickly and just five days later the Siege of Tsingtao began on August 27, 1914. The siege lasted until November 7, 1914, when the German garrison finally surrendered after a long and bloody struggle. That struggle involved one of the first uses of air power in warfare and, if the story is to be believed, the first air-to-air kill was scored by a German pilot against the Japanese outside of the city.

Tsingtao: A German Enclave

The Germans had ruled Tsingtao since 1898. During that time, they built it from a small village into a stunning city that was well-served by an active harbor. The German treaty, however, had not been kind to the Chinese. First, villagers who had previously lived there for generations were relocated up the coast, essentially at gunpoint. Once the way was clear, the Germans torn down the villager’s houses and laid out a modern street plan, built wharves, and constructed warehouses. They even erected a locomotive works.

The Germans called the port area “Kleiner Hafen”, which translates from German as “Small Port”. The Jiaozhou Bay, which the Germans called the Kiautschou Bucht, offered excellent shelter for merchant ships. As well, the Germans opened Tsingtao-Jinan Railway Line so as to move cargo between the Chinese hinterlands to the port. They built multiple schools and religious institutions and soon Tsingtao boasted the highest educational standards in all of China.

With its well-ordered streets, beautiful buildings and the port and nearby beach, Tsingtao was considered a paradise. Even the Chinese viewed Tsingtao as an example of what China could become once free of Western influence. As a result, many nations had designs on it — if only Germany could be thrown out of Asia.

A Few Primitive Aeroplanes

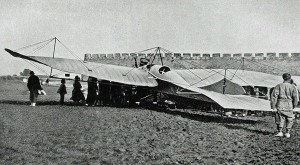

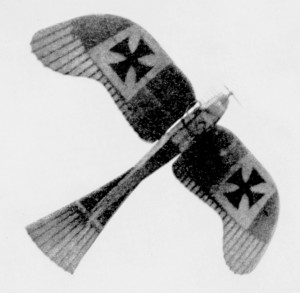

At Tsingtao, there were just two German military pilots plus an Austrian military pilot. Together, they had two serviceable airplanes when the Great War began. The monoplanes were the venerable Rumpler Taube type with their trademark, graceful birdlike wings. The German pilots deployed with the German Navy’s Seebatallion — OberLeutnant (First Lieutenant Navy) Günther Plüschow and Leutnant (Second Lieutenant Navy) Friedrich Müllerskowsky. The Austrian pilot was named Leutnant Clobucz.

The two Taube monoplanes carried no armament, however. As well, the two pilots were novice aviators, just as most pilots were at the time. Their aeroplanes had just been uncrated from having been recently shipped to Tsingtao, arriving in July 1914. After the first was assembled, Lt. Plüschow practiced extensively with the new aeroplane. When he was satisfied, the pilots then uncrated and assembled the second Taube. As a result of his inexperience, Lt. Müllerskowsky crashed his Taube. It was a simple mistake on take off. He was badly injured and was unable to fly again. The plane was a wreck, completely unrecoverable. This put half of Germany’s pilots and aeroplanes out of service for the rest of the siege.

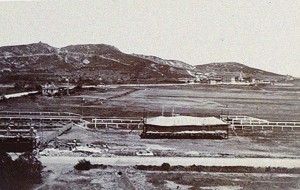

Despite this setback, Lt. Plüschow began to regularly flying missions from the improvised airfield that the two men had selected in Tsingtao. The airfield, if you can call it that, had been a racecourse prior to the war. The space inside the horse track was flat and smooth, although it measured just 600 meters long and 200 meters wide. Worryingly, the area was surrounded by mountains, buildings, and rocky outcrops.

On the day that the war was declared. Lt. Plüschow was out flying a scouting mission. When he returned to Tsingtao, he was flying at 1,500 meters of altitude. Suddenly, his Taube’s engine sputtered and quit. Realizing that he could make the field, he executed a dead stick landing. In his inexperience, he crashed the plane. Luckily, he survived. Though the engine was undamaged and the Taube was repairable, the damage was extensive, particularly to the wings.

It had to be rebuilt, an effort that took the first nine days of the war. With some foresight, the German Imperial Navy had shipped spare wings and other parts along with the two monoplanes in crates. These were opened and to everyone’s dismay, the spare wings were found to be rotted and unusable, having suffered damage during transportation. Likewise, there was no spare propeller. The Chinese in Tsingtao were enlisted to manufacturer new wings from local wood and cloth. As well, they built a new propeller, but Lt. Plüschow found that it performed poorly. Due to its poor balance, he had to run the engine at 100 rpm less than was possible with the finer German-made prop. This reduced his Taube’s speed considerably. Further, given the prop’s poor construction, it tended to wear and slowly come apart during each flight. Thus, he required a new propeller be made and fitted after every flight.

Arrayed against the Germans on the Japanese side was a far superior force. The Japanese Army brought four Maurice Farman MF.7 biplanes, a box-like construction of wood and wires that was under powered and had more in common with the Wright Flyer in design than with later World War I types like the Sopwith Camel or Albatros D.III, and a Nieuport IVG2 monoplane. As well, the Japanese Navy brought a single three seat Maurice Farman and three two-seat versions of the plane, fitted with floats so it could operate off the water. These were carried to Tsingtao on Japan’s first seaplane carrier, Wakamiya.

During the conflict, the ship lowered the Farmans into the calmer waters of the bay and they would take off to perform reconnaissance and light bombing raids. After a short while, to reduce the workload required to launch each sortie, the four Navy Farmans were moved ashore. They flew all of their subsequent missions from the beach while Wakamiya stood by offshore with supplies, fuel, and spare parts.

When the Japanese forces arrived to lay siege to Tsingtao at the beginning of September 1914, Lt. Plüschow’s mission was uncomplicated. He was called on only to observe the Japanese Army ashore and the Japanese fleet as it blockaded the Kiautschou Bucht. He would take off, count, and identify the various ships surrounding Tsingtao’s outer bay. Additionally, he observed any movements of the Japanese Army forces on the land, including the placement of their artillery. Once back on the ground, he wrote down what he saw and reported back to the higher German Naval officers who were in charge of the defense.

From time to time, Lt. Plüschow attempted to drop small bombs on various Japanese ships. These were ineffective, very light and improvised munitions, serving as little more than a nuisance to the Japanese. Likewise, the Japanese attempted the same against the Germans.

Two Opposing Naval Fleets, Plus the Allies

To ensure an effective blockade, the Japanese fielded several cruisers, including the battleship Suwo, which served as the flagship, and two obsolete battleships, Kawachi and Settsu, plus the battlecruiser Kongo and her sister ship, Hiei. Later, the destroyer Shirotaye joined the blockade as well as the Japanese cruiser Takachiho. Further, he British Royal Navy supported the Japanese fleet. The pre-dreadnought HMS Triumph and the RN destroyer HMS Usk were deployed from Britain’s China Station.

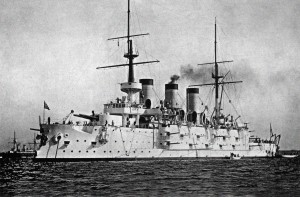

On the German side, the only ship that the Japanese were seriously concerned about was the Austro-Hungarian cruiser, SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth. The Germans fielded several gunboats, including Jaguar, Cormoran, Iltis, and Luchs, plus the aging torpedo boat SMS S90. These boats were small, but still a threat. The value of these small German gunboats and the old torpedo boat SMS S90 was proven when on August 22, a passing Royal Navy ship, HMS Kennet, a Thornycroft River Class Destroyer, was damaged in a combined attack by SMS S90, SMS Lauting, and a shore battery that the Germans had located off Tsingtao. HMS Kennet found the SMS S90 too difficult to hit given the smaller vessel’s speed and manueverability, despite firing 136 rounds and one torpedo at her. Still, SMS S90 escaped undamaged and returned to Tsingtao. However, before leaving the engagement, SMS S90‘s own guns had taken out one of HMS Kennet‘s guns and killed five of her crew.

Subsequently, SMS Jaguar sortied and sank the Japanese destroyer Shirotaye. Later still, on October 17, SMS S90 scored again when it sortied from the harbor and sank the Japanese cruiser Takachiho. Unable to return through the blockade despite several attempts and running low on the fuel, the German gunboat captain took SMS S90 close to the Chinese coast and scuttled her. He and his crew were subsequently imprisoned in neutral Nanking. Based on its performance during the Siege of Tsingtao, SMS S90 is probably the most successful gunboat in naval history.

Several Air Power Firsts

On September 6, one of the Japanese Navy’s Farman MF.7 seaplanes flew the first air-sea battle in aviation history. The seaplane carrier Wakamiya ordered one of its four Farman biplanes to be lowered into the water and take off on an attack mission. The order was to bomb SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth and SMS Jaguar. The Japanese pilot took off from the water, flew the roughly 40 km to Tsingtao, identified SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth, and dropped a small bomb that he had stored in a small basket aligned next to his seat. For aiming, he had no bomb sight. He simply flew overhead and held the bomb out at arm’s length in one hand. When he estimated that he was in the right position, he dropped the bomb and watched it fall — and miss.

He tried the same against SMS Jaguar. He missed the gunboat too, despite having observed the arc of how a bomb fell when he dropped it from his aeroplane, probably as it was a much smaller target. Then the Japanese pilot flew back to report the results of his mission. The attack was the first time in history that a ship-launched aeroplane attacked another ship.

Another first was the Japanese night attack by air. In that era, pilots rarely attempted to fly their rickety aeroplanes at night, let alone perform combat missions in the dark. There were no radios or navigation aids. Airfields were improvised and unlighted, making landing a treacherous prospect, though on a Moonlit night it was possible. There were no radar systems or control towers to help guide a pilot back to the field. The cockpit instruments, what few of them there were, typically included only a compass, an oil pressure gauge and an RPM indicator. These too were unlit.

Pilots navigated not by the stars above but by the lights of villages, towns, and cities below. The shorelines could be seen below as well. Most planes couldn’t fly more than a few dozen kilometers anyway. Despite these challenges, the Japanese decided to take advantage of the night and fly the first night combat mission in history — it was simply a reconnaissance mission and there are no records indicating what the pilot actually saw and reported back.

Not all of the firsts were achieved by the Japanese, however. In early September, Lt. Plüschow became the first aviator to be fired upon by flak from navy ships. As he flew overhead, cruising along at something between 1,000 and 1,500 meters of altitude, the Japanese ships below suddenly opened fire. They managed to hit his plane, though the damage was light. He was able to turn for Tsingtao and make it back safely. After that, he elected to fly about 2,000 meters of altitude, safely above the range of the ship’s small arms fire. Ships of that era had no anti-aircraft artillery.

Shortly thereafter, the Japanese launched an eight aeroplane raid using a combined force from both the Japanese Navy and Army on Tsingtao. This was perhaps the largest air attack yet assembled globally, though that record wouldn’t hold for more than another few months. Coincidentally, at that exact moment, Lt. Plüschow was himself flying over Tsingtao in his Taube. He was surprised when one of the Japanese aeroplanes came close and tried to attack him. The Japanese pilot apparently took shots with his pistol, though he missed. Uninjured and unarmed — and as such unable to return fire — Lt. Plüschow turned his aeroplane away and escaped by climbing into a cloud layer at approximately 2,500 meters of altitude. He flew away landed safely at nearby Haichow, refueled, and then flew back to the racetrack airfield at Tsingtao.

Some days later, Lt. Plüschow again encountered a Japanese aeroplane, one of the Japanese Navy Farman MF.7 biplanes that was performing reconnaissance over Tsingtao’s harbor. Since his earlier encounter, he had started to fly with a pistol. Pointing his slightly faster Taube aeroplane at the Japanese seaplane, he closed the distance slowly, came alongside, drew his pistol, and shot at the Japanese pilot. It isn’t clear if he badly wounded him or killed him outright, but the Japanese plane subsequently crashed. Thus, Lt. Plüschow claimed to be the first in aviation history to achieve an aerial victory. The Japanese pilot died.

Lt. Plüschow’s claim of a victory, however, remains unconfirmed. Japanese records do not support the loss of any of their pilots or aeroplanes. Perhaps it would be better to claim that he started the venerable tradition of over claiming aerial victories, a practice that has continued from 1914 until recently, though nowadays aerial combat is so vanishingly rare that air-to-air kills are almost unheard of.

The End of the Siege of Tsingtao

Throughout the siege, Lt. Plüschow proved himself to be a jack of all trades. He and an Austrian pilot, Lt. Clobucz, having recognized that the city would soon fall, constructed a biplane seaplane of their own design by the harbor. With the imminent fall of Tsingtao to the Japanese and British, the German governor asked Lt. Plüschow to fly a final dispatch message out of Tsingtao.

On the morning of November 6, he flew out, hoping to make it southward to safety. He flew over 250 km before finally crashing into a rice paddy. He recovered the documents and burned his aeroplane, a sad ending for one of the world’s first true combat aeroplanes. He had escaped Tsingtao just in time. That very night,the Japanese made their final assault on the city and defeated the German defenders. The garrison was taken prisoner and sent to Japan for the rest of the war. Incredibly, despite being outnumbered six to one on land, three to one by sea, and nine to one in the air, the Germans had held out for two months, only surrendering when they ran out of ammunition.

The documents Lt. Plüschow carried out of Tsingtao were delivered ultimately to Berlin, though not by air. Rather, they were taken by a ship that Lt. Plüschow helped arrange, using a neutral nation’s diplomatic pouch. Thereafter, Lt. Plüschow set off alone and on foot for Germany. What followed was a journey that took nine months. He first went to Dauschou, where the local Chinese overlord feted him with a nice welcome party. From there, he obtained papers to continue southward through China. Then he worked his way to Nanking on board a Chinese junk. From there, he jumped a train to escape to Shanghai when he was spotted in town. Realizing that he was about to be arrested, he made his escape. From Shanghai, with no place to go and no money, he got lucky and ran into an old German friend who took him in. Hearing his story, the old friend arranged false travel papers for him that identified him as a Swiss national and provided him with money for the voyage home.

With his false travel papers, he booked passage to Nagasaki, Japan, arriving in the very nation against which he had been recently fighting. Without delaying long, he booked further ship passage to Honolulu, in the US Hawaiian Territory. From there, he sailed onward to San Francisco, where he arrived at Angel Island and was processed through US Immigration. By January 1915, he had made it by train to New York City.

Soon after arriving, he was shocked to see a report in the newspapers that the Allied nations were seeking his whereabouts. They had heard of his exploits as Germany’s most famous Asian aviator and wanted him captured. Ominously, the newspapers noted that he was easily identified by a Chinese dragon tattoo on his arm — something that he had done while in China. The newspapers also reported that the authorities suspected that he was in already New York, though how they had guessed that is a mystery.

Even if the United States was still neutral and not yet involved in the Great War (the US would join the war effort two years later), Lt. Plüschow realized that he could be easily spotted as long as he remained in New York. He considered trying to gain entry into the German Consulate in New York City, but could not conceive of a reason for a Swiss national to visit there. Not far away, however, unbeknownst to him, was a potential way out. However, he had no way of knowing that New York City was a hotbed of German espionage activities. These were operated under Count von Bernstorff, who was based in Germany’s Washington Embassy and regularly traveled to New York’s lower Manhattan district. The two never met.

Without money or a place to stay, once again Lt. Plüschow was lucky. He encountered another friend from Berlin in New York City. The man took him in and helped arrange transport from New York to Italy by ship. Once at sea, he felt he could breathe easier, but his luck deserted him after the transatlantic crossing. Arriving at the gateway to the Mediterranean Sea, the ship stopped to take on fuel and supplies at Gibraltar. British authorities boarded and identified him. He was removed from the ship and placed under arrest before being sent to England to be imprisoned for the duration of the war.

Once in England, he was held at Donington Hall in Leicestershire. Then, on May 1915, quite incredibly he escaped, making his way out of the Hall and through a tall fence lined with barbed wire. To achieve this, he used the cover of a passing storm. Quite simply, he slipped away into the night. Despite having a bulletin issued for his arrest by Scotland Yard, he evaded capture for many weeks. To blend in, he dressed as a dock worker. He wandered London, trying to work out how to cross the English Channel. At one point he had photographs taken of himself by the port as souvenirs. While there, he carefully watched the movements of the ships arriving and departing, realizing that the shipping schedules were not published. At one point, he visited the British Museum, wandering the exhibits. Finally, he was able to sneak onboard a Dutch ferry called Princess Juliana, and thus made passage to the Netherlands. As the Netherlands was a neutral country, from there he was able to return easily to Germany. He arrived in Berlin in July 1915 after almost five months in England.

Proclaimed a hero, he was awarded the Iron Cross 1st Class and promoted to the Naval rank of KapitanLeutnant. Additionally, he was assigned to command the Imperial Navy’s seaplane station at Libau, which was part of the Russian front of Germany’s defenses during the Great War. He served there uneventfully for the rest of the war.

Gunther Plüschow was the only German combatant to ever escape a POW camp in Great Britain — in either of the world wars. With this said, at least one other German prisoner escaped from captivity while being held in Canada during World War II. For more than a decade after the end of the war, Gunther Plüschow continued to fly. He was recognized as an aviation pioneer and he made good use of his reputation by scouting South America by air. He became a documentary film maker, cataloging his experiences on film when he returned to Germany from Patagonia, where he had lived for over two years. During that time, he had flown all around the southern end of South America, including across the mountains to Chile.

After publishing a book and a movie, Günther Plüschow and his flight engineer, Ernst Dreblow, returned to Argentina to explore some more by air. Sadly, they both died in the crash of their seaplane at Brazo Rico, Lake Argentino, Argentina, on January 28, 1931. It was a terrible, though epic end. The two crashed onto Perito Moreno Glacier. Today, a monument marks the site of the crash. His death is commemorated each year in Argentina and Chile. Naturally, the seaplane he flew in Argentina, a Heinkel HD 24 that carried tail number D-1313, was nicknamed, “TSINGTAU”.

One More Thing

The infamous reputation of the Japanese military in wartime is largely defined by American experiences of World War II. However, during the Great War, the Japanese performed far more admirably and honored, belying the claim that the samurai tradition of Japan inevitably lead to atrocities being committed against prisoners. While later POW experiences in Japan during the 1940s were horrific, with prisoners experiencing severed deprivations, torture, starvation, and executions, the German prisoners from Tsingtao fared very well. They numbered 4,700 in all and almost all of them survived the war. Respect was mutual between the Japanese and the Germans. In fact, the ship’s orchestra from SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth regularly entertained Japanese and foreign guests with performances of Bach and Beethoven concerts during their captivity. The POWs were well-fed and well-housed. When the war ended, it took over a year for them to be finally repatriated to Germany. Still, 170 of Germany’s former POWs chose to remain in Japan afterward, a gesture symbolic of their positive experiences there.

What an incredible part of aviation history! I knew very little about WWI – nothing about what you have covered here. You wove politics, flight, and patriotism so well. What a guy Plushow was. He certainly was clever and determined to get back to Germany. Perhaps more than a ‘little lady luck’ was on his side. I intend to read some of your previous stories!

Where did you get the idea he posed for photos at the London docks?