Published June 3, 2012

By Thomas Van Hare

Today in aviation history, exactly sixty-four years ago, in 1948, in the clear skies over Israel, the newly formed Israeli Air Force scored its first victories. The small aviation contingent of the newly formed Israel Defense Forces (IDF) had little equipment, no supplies, almost no organization and few pilots. Most of those born in what was then Palestine could fly only light aircraft such as the Piper Cub. Few had any experience in combat. Just a handful had flown in the RAF or in the USAAF and had gained experience in high performance fighter aircraft.

Based on their early analysis of the tactical and strategic challenges before them, the Israelis recognized that their new country would rely on its air force for security more than any other component of its military. Soon, they recruited volunteer pilots from among the ranks of those who had flown in World War II against the Nazis. Additionally, they began an intensive effort to find fighters and bombers and smuggle them into Israel.

In those early days, the Egyptian Air Force was flying over Israel with impunity, knowing that the Israelis didn’t have a single combat aircraft to their name. What they didn’t know was that the newly founded IAF had only just managed to secretly acquire and bring in four fighter aircraft. The aircraft were the Czech version of Nazi Germany’s famed Me-109 and were known as the Avia S199. With an ill-fitted engine, huge paddle-bladed props and narrow landing gear, the Avia S199s were as dangerous (or more so) to their unseasoned pilots as they were to the enemy.

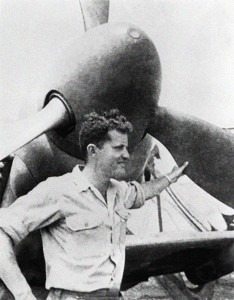

Among the new IAF pilots was Mordechai “Modi” Alon. Unlike many of the other new Israeli pilots, Modi Alon had been trained by the British during World War II and had flown the P-51 Mustang. His skill in high performance fighters was excellent, even if he had never served in combat. On Ben Gurion’s order, he had traveled secretly to the Czechoslovak airfield at Ceské Budejovice. There he had trained on the Avia S199, learning its quirks and gaining valuable experience in the airplane.

For a pilot who had trained in the RAF, it was a strange experience flying an S199. The plane was a lower performance version of the Nazi’s leading front line fighter, the Messerschmitt Me-109G. After a few short weeks learning the basics in Czechoslovakia, he returned to Israel and prepared for the arrival of the new airplanes — of which 25 were purchased.

The first four aircraft were smuggled into the country and arrived in crates over the night of May 20-21, 1948. Immediately, the newly formed IAF maintenance branch started the task of assembling the aircraft, a job that would require nine days of hard work.

Based on a UN Security Council Resolution, Israel’s independence was declared in May. Instantly, the surrounding Arab nations invaded. Overwhelming forces from all directions were closing in on the newly formed state. Its newly formed military had been growing during the months leading up to independence, but Israel’s forces were absolutely outnumbered. Their only hope was that the Jewish forces might be superior to the Arabs in skills, equipment, logistics and overall capabilities — though they were outclassed by the British.

The future looked grim for the young state, despite that the world’s major powers had immediately called to recognize its existence (the first call had been received from President Harry S. Truman of the United States, despite the objections of some of his advisers — Truman thereby started a long and positive relationship with the the young country).

To the south, the Egyptian ground forces began marching up the coastal road toward Tel Aviv. In their path, very few defenses were in place to protect what was the nation’s largest city. It seemed that the Arab promise to “push the Jews into the sea” would soon be a reality with the mass slaughter of an entire city. Something had to be done, yet the best the newly formed ground units of the IDF could muster was an undermanned delaying action along the road.

It was in this context that the new Israeli Air Force was formed. Its first (and only) fighter unit, the 101 Squadron, was commissioned on May 29, 1948. Modi Alon was designated its commander, even if a combat experienced American volunteer pilot named Lou Lenart (himself a World War II veteran of the Pacific War) was given command of its aircraft once the planes were in the air.

The 101 Squadron had its four Avia S199s in a hangar at Ekron. Originally, their first mission had been intended to be an attack on the Royal Egyptian Air Force (REAF) air base at El Arish. This was conceived as a fine way to announce that the skies over Israel would no longer be uncontested. However, with the approach of the Egyptian ground forces toward Tel Aviv, the IAF made its first command decision — they would instead bomb the Egyptian army column, even if the aircraft had only just been assembled and their engines had not even been test run. The guns had not been test fired nor sighted. Nonetheless, the first mission would have to be flown without delay.

Lou Lenart (USA), Modi Alon (Israel), Ezer Weizman (Israel) and Eddie Cohen (South Africa) took off in the late afternoon and attacked Egyptians near Isdud, only about 10 miles from their airfield. Each dropped two bombs and strafed the enemy column. They inflicted only slight damage. Worse yet, one of the Avia S-199s was shot down by ground fire and its pilot, Eddie Cohen, was killed while attempting a landing at Hatzor, which he accidentally mistook for Ekron.

Modi Alon’s aircraft was also damaged on landing back at Ekron, demonstrating the tricky nature of the S199 and its narrow landing gear. Alon would later comment that he had lost half his air force on the first mission alone.

Incredibly, the attack bought the Egyptian advance to a halt. The Egyptian ground commanders overestimated the threat of the new IAF and demanded air support if they were to proceed. They held, just a few miles from Tel Aviv, waiting for the Royal Egyptian Air Force to respond and clear the skies of the enemy. The REAF, however, found itself on its back foot, surprised at the sudden emergence of a defensive air force over Israel. It would be the closest the Egyptian ground forces would ever come to Tel Aviv and soon afterward, they withdrew back toward to the Sinai.

Just days later, on June 3, 1948, two REAF C-47 Dakotas, escorted by two REAF Supermarine Spitfires, flew in from the sea to bomb Tel Aviv. The Egyptian Dakotas, both of which had been converted into bombers, had been bombing Israel almost daily for over a week, inflicting hundreds of civilian casualties. The Dakotas would orbit while the crew in the back simply threw their bombs out of the cargo door at the city below. Without aiming, most of the casualties were civilian, but they could hardly miss a target the size of a city. The population could do little but watch helplessly during each attack.

When reports came in that the C-47s were on the way again, the IAF had only one serviceable Avia S199 able to fly — the other surviving plane was being repaired. Nonetheless, Modi Alon took off in the late afternoon sky in hopes of intercepting the C-47s and their Spitfire escorts. First, he flew the few miles to Tel Aviv. Almost immediately, he picked out the two C-47s as they made orbits over the city with two Spitfires in escort.

Recognizing that the C-47 Dakotas would be the best targets and easiest to shoot down (and also tactically most effective since it was the bombs doing the damage to the city below), Modi Alon flew first westward out over the Mediterranean Sea. From there, he could approach with the sun behind him, masking his attack. Turning around at high speed, Alon bored in from below and at the last moment, zoomed up behind the first Egyptian C-47. With a long burst of fire from his guns, he sent it plummeting to earth.

Avoiding the two Supermarine Spitfires escorts, he flashed past and turned tightly around to come back again for a head-on pass against the second REAF C-47. The target, slow and completely over-matched by Alon’s fighter, was a “sitting duck.” Once again, he lined up and fired as the two Spitfires looked on, unable to position themselves to defend the transport-turned-bomber C-47 as it slowly lumbered into a turn to try to escape over the sea. Alon’s bullets riddled the second C-47, which staggered out over the Mediterranean before finally crashing into the sea. With the job finished and fearing an engagement against two fighters, Alon then dashed quickly away at full power. He left the two Spitfires of the Egyptian Air Force far behind.

Ever resourceful, the civilian population of Tel Aviv learned who the pilot was and where Alon was quartered and the following morning, his room was filled with flowers and thank you notes.

Alon’s two aerial victories shook the REAF to the core. Above all, the Egyptian commanders recognized that the C-47 cargo plane was never intended to serve as a bomber — it lacked any defensive armament or armor. Therefore, to send more would have been suicide for their pilots. Overestimating the power of the newly formed IAF, the Egyptian Air Force commanders decided that bombing missions over Tel Aviv would have to cease at once. Had they known that the entire Israeli Air Force at that moment consisted of but one fighter plane, they would have likely made other decisions, but as it was, the two air-to-air victories scored by Modi Alon single-handedly ended Egyptian aerial bombing. Instead, Egyptian fighter aircraft would take to rapid strafing attacks against the city from time to time. Never again would any EAF aircraft drop bombs on Tel Aviv.

A few weeks later in July, Lou Lenart ended his volunteer service to the new Israeli Air Force and returned to the USA. With his departure, Modi Alon was made the sole squadron commander of the 101 Squadron. Two weeks later, in the early evening of July 18, Modi Alon scored his third victory in aerial combat. Additional Avia S199s had been imported and assembled and three were returning from a ground attack mission when they spotted a flight of two REAF Spitfire Mk. VCs. Rapidly assessing the situation, Alon maneuvered in behind the pair and shot down one of them, piloted by one of Egypt’s best pilots, Wing Commander Said Afifi al-Janzuri.

By September, Alon would participate in Operation Velvetta, which ferried Czechoslovak Spitfires to Israel — a significant upgrade from the S199s. As the IAF expanded, it shifted its missions to more and more ground attack while simultaneously establishing control of Israel’s own airspace.

Sadly, Modi Alon would not survive to see the end of the War of Independence. On October 16, 1948, he and Ezer Weizman took off from Herzliya once again in a pair of the unreliable Avia S199s. Their mission was to attack Egyptian ground forces along the coastal road.

After the attack, when returning to base, Alon experienced trouble lowering his plane’s landing gear. Not wishing to destroy one of the precious few fighter planes in a belly landing, Alon tried forcing the landing gear down by pulling high G turns and various other violent maneuvers. One of the wheels remained stuck in the wing, while the other dropped down into place.

Whether it was from the maneuvers or from another maintenance issue with the aircraft, his S199’s engine suddenly started to fail. Streaming white smoke and faced with few options at low altitude, Alon found he couldn’t maintain altitude. He was apparently attempting to crash land but lost control of the plane due to asymmetrical drag from the one wheel down. From about 1,000 feet of altitude, he stalled and spun in. Some of the other pilots would later speculate that he lost consciousness from smoke in the cockpit. On hitting the ground, the plane burst into flames. He was killed instantly.

Modi Alon was survived by his wife, Mina, who was three months pregnant at the time. His daughter, who would be named Michal, would later serve her mandatory IDF service with 101 Squadron.

The 101 Squadron today remains the first and foremost unit of Israel’s elite air force. Established in the darkest days of the War of Independence, the squadron is testimony to the leadership, daring and personal courage of Modi Alon, Israel’s first successful fighter pilot.

What a great story. The first truce, June 11, 1948 is also my birthday!