Published on June 25, 2012

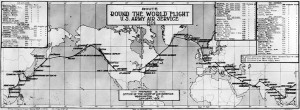

In 1924, two great nations were pressing the limits of aviation to prove that no part of the civilized world was out of reach of the airplane. Britain’s Royal Air Force had assembled a team of flyers to become the first nation to complete a circumnavigation of the globe by airplane. Under the leadership of Squadron Leader Archibald Stuart MacLaren, they planned to fly eastbound around the world in a Vickers Vulture II amphibious biplane powered by a 450 hp Napier Lion engine. Meanwhile, the United States Army Air Service had assembled its own team under the leadership of Major Frederick L. Martin. This would involve four specially modified Douglas DT-2 torpedo planes with 420-hp Liberty V-12 engines that were fitted with extra gas tanks and interchangeable wheels and floats — the Douglas World Cruisers (DWC).

For the US Army, the flight was key to proving America’s leadership in the air and Major General Mason M. Patrick, Chief of the United States Army Air Service, stated, “The flight would secure for the United States, the birthplace of aeronautics, the honor of being the first country to encircle the world entirely by air.” Five Douglas World Cruisers were built for the round-the-world flight. One would be used for testing and training and the other four aircraft were named after American cities on the four points of the compass — Chicago, New Orleans, Boston and Seattle — thus representing all parts of the United States. For good luck, and as champagne was outlawed during the early years of the Prohibition, each aircraft was christened with water from the harbor of its namesake city, including Mississippi River water for the New Orleans.

The American Flight Departs Westbound

On March 27, the American flight took off from Santa Monica, California, en route to Seattle, where the wheels would be changed for floats. From there, the flight would begin officially on April 4, 1924 as the four Douglas World Cruisers lined up for take-off on the first leg to Alaska. Maj. Fredrick L. Martin, who would head the operation, flew the Seattle, 1st Lt. Lowell Smith flew the Chicago, 1st Lt. Leigh Wade flew the Boston, and 1st Lt. Erik Nelson flew the New Orleans.

Right away, the Seattle had its first mishap — on take-off, the aircraft shattered its prop against the water, damaging a pontoon and putting a hole in the fuselage. Two days later, repairs were completed and the flight was ready to depart a second time. After departure, disaster struck yet again for the Seattle. Lost in bad weather, it crashed into a mountain, leaving just three planes to continue around the world. The flight’s commander, Major Martin, was missing. Lt. Smith of the Chicago took over the leadership of the flight and the three remaining planes flew onward a week later across the Bering Strait to the Soviet Union. Then they began working their way southward toward Burma and India. On the way, they received reports that the Seattle’s two man crew had hiked out of the Alaskan wilderness uninjured, despite the harsh early spring weather.

The RAF Team Flies Eastbound

Meanwhile, the British RAF team had received the blessing of the King of England and departed Calshot Seaplane Base, near Southampton, England, in their Vickers Vulture II on March 25, 1924. They flew over France, Italy and across the Mediterranean to Cairo, and from there landed in various British possessions in the Empire along the way. Leaving Allahabad, India, they had radiator problems which forced them down at a small coastal bay at Akyab Island in Burma, short of their planned stopover destination at Rangoon. They sheltered and worked on repairs for the next leg of the trip. Their plan was to continue onward through China, Japan and the Soviet Union, cross the Bering Strait to Alaska, and then transit east through Canada. They would then fly the Atlantic Ocean to Portugal and then proceed up the west coast of continental Europe to Britain.

On this date in aviation history, June 25, 1924

With the repairs completed, the RAF team attempted to take off from Akyab Island, but their plane overturned and was wrecked. Another aircraft, which had been shipped previously to Tokyo for use as a spare, was brought over as a replacement while the flight crew waited. Finally, on June 25th, the second Vickers Vulture arrived. Unbeknownst to the British RAF team, however, that very day, the three planes of the American flight flew overhead on the way to Allahabad, India. Shortly thereafter, the RAF team took off successfully and worked their way up to the Kamchatka Peninsula in the Soviet Union. When weather forecasts were favorable, they took off for the flight across the Bering Strait — yet forecasts were wrong and a deep fog forced them down at Bering Island, on the Soviet side of the strait. They beached the badly damaged plane and were forced to abandon the rest of the attempt. The RAF team was rescued some days later by a Soviet ship.

The Americans Continue Onward

The American team pressed on, landing in Calcutta, India, on June 26 to replace the floats once again with wheels for the long overland portion of the flight through southwest Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. As originally planned and hoped, they reached Paris on Bastille Day to much celebration. They were met by Gen. “Blackjack” John Pershing and the French president, who then accompanied them to the Olympic games, which were in France that year. Afterward, they flew on to London and Hull, where major repairs were accomplished. They arrived at Orkney Island, Scotland, on July 30th sporting floats for the transatlantic flight to come. After four days of rest, the crews departed on August 3rd. Once again, trouble struck as the Boston was forced down in the middle of the Atlantic short of Iceland. The crew was rescued by a Navy ship but the plane was lost during an attempted recovery. When the flight crews were reunited on September 3rd in Icy Tickle, Labrador, the original P318 DWC prototype aircraft was flown up to join the other two. It was renamed Boston II and with the Boston’s original crew would continue onward for the rest of the way across the United States, landing in Seattle on September 28th.

The American flight had taken six months and six days. It was a logistical feat, demonstrated by the fact that almost all of the time was spent on the ground doing maintenance at various stops along the route and waiting out weather for favorable conditions. In all, the flight time totaled to just 371 hours, during which they had visited 28 countries. The American flight was a triumph — by circumnavigating the globe, the Douglas World Cruisers had finally proven that aviation had conquered the world, connecting every possible nation to one another. For the Douglas Aircraft Company, the flight would give birth to the company’s new motto, “First Around the World / First the World Around.”

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

Besides the British, four other countries would try to circumnavigate the globe in 1924. France’s Captain Pellitier D’Oisy departed Paris and made it to Shanghai, China before wrecking his Breguet biplane. Argentina’s Maj. Pedro Zanni, flying a Fokker C-IV biplane, departed Amsterdam and made it as far as Kasumigara, Japan, before ground-looping and wrecking his plane on take-off. After taking off from Pisa, Italy’s Lt. Antonio Locatelli joined the American flight in Europe to make their own attempt in a German Dornier Wal flying boat. Lt. Locatelli caught up with the Americans in Iceland, but then misjudged his fuel load, ran out of gas and force-landed 120 miles short of Labrador in open seas — he would be rescued by the US Navy ship USS Richmond. Portugal’s Commander Brito Pais departed Lisbon, but after a crash in India, later ended up abandoning their attempt in Macau, where they settled down for awhile and enjoyed their newly earned status as the “Portuguese Eagles.” These failed attempts truly demonstrate the difficult challenges faced by the Americans in their 1924 flight — five of the six nations attempting a world flight fell short and only the Douglas World Cruisers completed the journey.

See Original Footage of the Douglas World Cruisers and their Flight Around the World

(Source: US National Achives; 54 minutes)

I am the granddaughter of Squadron Leader Archibald Stuart MacLaren who led the British attempt to fly round the world in 1924. You have a nice picture of the three of them.

I have been researching the flight for the past 20 years and am now finally going to Vancouver Island where the propeller of their Vickers Vulture is on the wall of the Officers Mess of HMCS Esquimalt.

I will be writing an article about this very emotional trip for me, and wondered if you would like me to submit anything about it to yourselves.

Vanessa —

I would like very much to read your article and, if you don’t mind, it would be wonderful to have the opportunity to consider it for publishing here.

Thomas.

Just to let everyone know, I am the grand daughter of one of the crew and I am starting to write the book about my grandfather’s world flight as well as his life!

Vanessa Ascough

I have only just picked up this message today. The article was published in Aeroplane Monthly magazine April edition

Vanessa

Dear Vanessa, I have inherited a large collection of photos from my Great Grandfather, who was based in Egypt between 1921-30. In the collection are photos of two long distance flight attempts, including your Grandfather’s. I have some photos in the collection of G-EBHO. Please contact me so that I can send them over if you like!

I have just picked up this message today and am so thrilled to hear that you have photos in your Great Grandfather’s collection.

Please do get in touch as I would love to see them

Vanessa