Published July 24, 2012

This article is dedicated to the memory of Sally Ride, America’s first woman astronaut, who, at age 61, passed away from pancreatic cancer yesterday, July 23, 2012. She will always be remembered as one of NASA’s brightest shining stars.

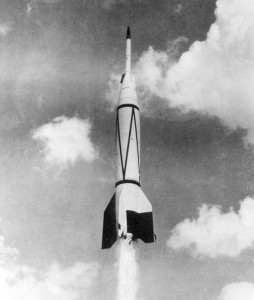

Today in aviation (and aerospace) history in 1950, marks the date of the first rocket launch from Cape Canaveral in Florida. The rocket, named Bumper 8, was the last in numerical sequence of a series of ambitious test launches that had commenced previously at the White Sands Missile Range. After a launch mishap that resulted in cancellation, Bumper 7 rocketed away five days later out of sequence, thus becoming the second launch from the then brand new Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, part of nearby Patrick Air Force Base, Florida.

Bumper 8, as all the Bumper series of rockets, involved a two-stage launch system, the first stage being a WWII era Nazi V-2 missile with an upper stage of a WAC Corporal sounding rocket. Bumper 8 flew a low angle trajectory seeking not altitude but distance. It flew to just 16.1 km of altitude, but would fly down range a total of 320 km. This was a trajectory repeated by the Bumper 7 launch as well. Bumper 8’s payload was a radio transmitter nestled behind a new Teflon nose cone undergoing testing in hopes that it would enhance protection against aerodynamic heating.

The altitude potential of the Bumper rockets was established eight months earlier when the Bumper 5 rocket’s upper stage set a record altitude of 393 km (the internationally recognized boundary of space is 100 km in altitude). By comparison, most spacecraft today fly at much lower orbital altitudes. The Bumper rocket series was designed to investigate temperatures and cosmic ray effects.

The Bumper program was managed by the General Electric Company, reflecting the growing partnership between NACA (and later NASA) and America’s privately held aerospace industry in the early days of the space program. Likewise, Douglas Aircraft Company built the second stage rocket and fabricated many of the V-2 launch parts, using German plans and expertise, from which the US was benefiting. The Bumper rocket tests were defined by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory under U.S. Government management. It was a landmark effort that had grown out of the successful launches at White Sands of the German V-2 rocket technologies, accomplished with the aid of a group of 126 German (former Nazi) scientists that had been brought to America as part of Operation Paperclip, lead by Wernher Von Braun.

While most Americans remember the Sputnik launch (the first satellite to attain orbit), it is interesting to note that the Bumper 5 rocket flew higher — it was a successful program even if five of the first six flights at White Sands failed in one way or another. Many lessons were learned and it is notable that the first two flights out of Cape Canaveral were both entirely successful.

At the newly created Cape Canaveral, another problem was also uncovered with the Bumper launches — but not a technical one. Ironically, it was hard to recruit personnel to man the station out at “the Cape”. The facility was remote, largely barren and far enough from good housing facilities that few wanted to be assigned there in the early years of America’s new space program. Less than two decades later, competition to get into the race to the Moon would be fierce and the once barren Cape had become a hive of activity that was studded with launch complexes.

Over the years, hundreds of successful rocket launches have been made from Cape Canaveral and the name is synonymous with America’s space programs. So on this day in history, it is fitting to recognize the history of America’s premiere space port by recalling a nearly forgotten time when the Moon still seemed a far reach.

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

At the end of World War II, America was lucky to have approximately 126 principal German rocket scientists literally walk into its arms. These scientists, the cream of Hitler’s rocket programs, were true pioneers of aerospace and rocket engineering. Incredibly, Hitler had ordered them assassinated en masse at the end of the war so as to prevent their capture. Instead, before the execution squad could arrive, the majority of them (over 100) slipped across the front lines into the hands of American forces on May 2, 1945, the very same day that Berlin fell to the Soviet Army. It was just two days after Hitler’s own suicide deep in his Berlin bunker and a time when everyone knew that the war was lost for Germany.