Published on August 5, 2012

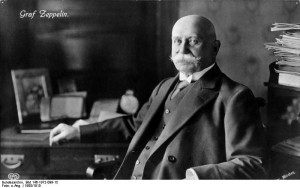

The year was 1898, and in nearby Manzell, Germany, one of the two partners in the venture stood on the porch of his family estate. Half of the funds for his venture, 400,000 marks of his personal fortune, were wrapped up in this dream with his partner, the aluminum maker Carl Berg. Although it was an equal partnership, one of the two men would become synonymous with Germany, flight and aviation history — a determined man and visionary, almost 70 years old, his name was Count Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin. It would take another two years before von Zeppelin’s dream would take flight — on July 2, 1900, his first airship, the LZ 1, would take flight over Lake Constance.

On this day in aviation history, we celebrate the birthday of von Zeppelin. Born in Baden, Germany, his first brush with aviation came in the 1860s when he traveled to America and volunteered with the Union Army in the American Civil War. He would serve with the Union’s balloon units where he got his first taste of flight. It would ignite a long smouldering interest in aviation that would finally culminate in his great contribution to aviation — the design of a rigid airship with motors.

On that fateful day in 1900, von Zeppelin’s wooden shed with his airship inside was towed out into Lake Constance in the Bay of Manzell. It was a particularly calm morning and the airship was launched into the air after much careful preparation. The 416 foot long aluminum and cloth craft lifted off and slowly turned, hovering for thousands to see. Filled with hydrogen, it was not a balloon but rather a rigid, framed machine that appeared like a long sausage. The LZ 1 slowly rose and maneuvered up, down, left and right. Control was awkward as the craft lacked the power to perform in almost anything but smooth, calm air. Nonetheless, it was a staggering success — for those lining the shores, it was clear that with more powerful engines, the craft could fly gracefully through the air and, unlike a balloon, the pilot could choose the direction of flight simply by turning the nose toward where he wished to go, whether that was with the wind or against the wind. For the first time, aeronautics had achieved truly controlled flight.

Despite success with more early flights that followed the LZ-1, it would be eight years and numerous failures and crashes before the Count would finally have his first buyer lined up — the German military. Each crash and each flight had been a learning experience and continuous improvements had been made. Moreover, his flights had caught the attention of the public, which followed news of each venture with eager interest. As the summer of 1908 came to Lake Constance, all von Zeppelin needed to do in order to firmly secure the military contract was fly his fourth airship, LZ-4, from the lake to Mainz on a 24-hour endurance test.

With careful preparations, he launched on August 4, 1908. At first, everything went well. The airship soared over the German countryside. Citizens below cheered and river boats on the Rhine blew their horns in salute. It seemed as if the entire nation was caught up in the Count’s dream. It had been a hard road: dozens of partners were behind him, their investments used up and yet still no contracts were in hand. Count von Zeppelin’s own fortune was exhausted as well and his wife’s family home in Latvia was mortgaged for the last time. This would be his final attempt. If he was successful, he would be vindicated. If he failed, he would die an impoverished, broken old man.

Despite excellent progress early in the trip, when the airship was nearing Mainz one of its engines started to act up. Ever cautious, the Count ordered a landing on the Rhine not far from the town of Oppenheim. With a huge crowd gathered along river banks, his crew made a few repairs to the engine and took back off. It was late and he decided to press on toward Mainz — the endurance test was a strict regime and had to be completed in 24 hours, traveling from point to point.

As he passed Mannheim in the middle of the night, after 1 am, one of the airship’s engines broke down completely. He forged ahead hoping for the best. Then, unexpectedly, the wind picked up. His zeppelin was fighting for every mile. Finally, it was clear that with the headwinds he would not make it on time. He had to complete repairs on the broken engine. He landed near the village of Echterdingen in a farmer’s field, not far from the Daimler engine works at Stuttgart. If their technicians could fix the motors, he would be able to make Mainz with ease.

Disaster Strikes Once Again

As the crews worked on the engines, a sudden summer storm hit. Powerful wind gusts lashed the LZ-4 and shook the craft. A gust of wind tore the airship from its moorings. There was nothing to do for the crew but watch as the airship careened across the field, carried by the storm’s winds. It struck a tree, igniting the ship’s hydrogen. In a massive fireball, the LZ-4 burned to the ground. As quickly as the storm had hit, it ended. Count von Zepplin’s attempt to make it Mainz had ended almost within sight of the city. The Count was at a nearby inn and was spared having to witness the storm’s rage.

Returning to the field on hearing the news, Zeppelin surveyed the wreckage. Everything was lost. A crowd gathered in the morning hours and, out of respect for the old man, they stood silently with their hats off. The Count could do nothing but stare silently at the wreckage. Finally, he turned and walked away without saying a word. It was the end.

His dream shattered and his fortune exhausted, the Count returned home by train. His dream of building great airships was done. He could not afford to build another and he had lost everything, even his home. Without the patronage of the German military, his airship company would be forced into bankruptcy.

The German people, however, had other ideas. His dream had become their own. The proud spectacle of his airship flying over the Rhine River had ignited the spirit of a nation. Within days, contributions started to pour in. Children sent their personal savings, social clubs sent their membership dues and numerous businessmen simply sent him money — all simply donations — begging that he try again.

The “Miracle at Echterdingen,” gave him the financing he needed to found the Luftshiffbau Zeppelin GmbH, a company that exists to this day. More importantly, he also founded Maybach Motorenbau, a subsidiary that would build the first engines with enough reliability to power his craft safely. The German military also purchased two of his Zeppelins, the first of many more to come, seizing the opportunity to cater to public will and further their goals.

From the ashes of the LZ-4, Count Zeppelin’s airships would symbolize a generation of both glory and tragedy. Even the United States Navy would purchase Zeppelins for its own naval reconnaissance and surveillance purposes — and the ZR-3 Los Angeles would be billed as “the silver needle that stitched New York to Europe in 81 hours.” From Germany, thousands would fly from Europe to North and South America in the highest style. Scheduled air mail service via Zeppelin would link the continents. The military would have an observation and bombing platform that would revolutionize warfare — in the eyes of historians, von Zeppelin’s creation would also bring about the era of “strategic bombing,” a sophisticated sounding military term that actually meant the bombing of civilian cities and industries. In the years that followed, over 160 airships were eventually built by the Zeppelin Company, including several for the United States Navy. By the 1930s, Germany’s Nazi Party would seize upon the great Zeppelins as a symbol of Nazi ascendency and power. From the ashes of Echterdingen would rise one of aviation’s greatest achievements.

Ultimately, however, just one would be remembered by the American public: the Hindenburg. But that is another story….

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

The Hindenburg and the other Zeppelins of the 1930s were designed to use non-flammable helium rather than hydrogen in their giant buoyancy cells. At the time, the USA was the number one producer of helium and was essentially the world’s only supplier. In the wake of the strategic bombing campaigns of Germany during the Great War (World War I) which saw Zeppelins dropping bombs over London, the United States had restricted access to foreign powers of its stocks of helium. The rationale was that Zeppelin raids were terrifying and would be best halted if helium was restricted. Presumably, hydrogen could be used safely and, in the event of another war, any Zeppelin bombers would be more easily shot down in flames. Even though the idea of Zeppelin bombing was outdated by the 1930s, having been long surpassed by the threat of high speed twin-engine and four-engine bombers, the helium restrictions remained in place well into the 1930s. Thus, when the Hindenburg burst into flame at Lakehurst, New Jersey, with the loss of many lives, the United States would quietly share blame for the tragedy. Despite the obvious pointlessness of the export restriction laws, helium would remain a controlled strategic asset by the USA for nearly five decades after the end of World War II.

This is an interesting story, but there are a couple of deviations. Echterdingen is about halfway between the Bodensee and Mainz, it is not “almost in sight of Mainz.” Mannheim is yet some distance north of Echterdingen so, from the story, It seems difficult to see how the LZ4 could have passed it. The explanation is that the test was not a one-way trip, but a round trip and the 24 hours was not a maximum time, but a minimum operational time. It was an endurance test. By the way, the Kaiser and the Kaiserin had previously made a trip on the LZ-4.

Regardless of whether the USA allowed export or not, helium was very expensive, and the gas bag of a Zeppelin is huge. The Graf Zeppelin II (sister ship of the Hindenburg) had a double envelope. The outer envelop was for helium while the inner envelop was to be filled with the much less expensive — and lighter hydrogen. Helium would have shielded the hydrogen from accidental fire and, being inert, the He would have suppressed any accidental fire should one happen anyway.