Published July 29, 2012

“I find myself between two giant, yellow wings that extend away over and under me. Behind us sits the motor, ready to launch us with its 50 horses to bear us up through the wind — and the propeller, which now rests its twin blades in silence, but in several seconds will whip around at 1,200 revolutions per minute amidst deafening noise.”

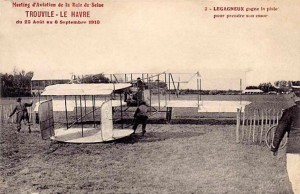

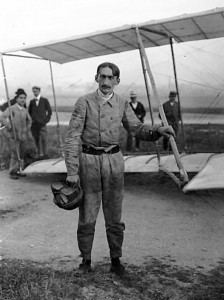

So wrote one of the first flight journalists, Eric Pallin, in an article entitled, “How it feels to fly.” Just a few days had passed since Frenchman Georges Legagneux had come to Sweden to take that nation’s first flight of an airplane on July 29, 1909. Three days earlier, coming through Sweden from Denmark (where he had flown a show a week earlier) while en route to St. Petersburg, Russia, Legagneux arrived by train at the invitation of August Soloman from the Swedish Motor Club. His Voisin-Farman biplane was packed in three boxes, one nearly misplaced but later found at South Station in Stockholm. Legagneux and his sponsors organized the transportation of his biplane to a nearby artillery field at Ladugårdsgärde where they would erect tent to serve as a makeshift hangar outside of the A1’s barracks at Valhallavägen. Inside, they reassembled the plane.

Two days of foul weather passed before this windless morning, a Thursday, would herald Sweden’s first powered flight of an airplane. Before a handful of observers, including the Motor Club representatives, Georges Legagneux first tested his plane in preparation for a large event planned for thousands of paying guests, which would even include the King of Sweden, Gustaf V. Legagneux could afford no mishaps, so with the dawn Legagneux rolled out his Voisin-Farman for his first test flights.

However, all is yet still. I look at the Frenchman. He is the very personification of tranquility. Between his lips is a softly drooping cigarette, instilling a feeling of safety. A signal is made to the helpers upon the propeller, who turn its two blades through. Then they ram it through once hard and with an infernal racket it starts, shaking the whole machine. “Allez,” I hear the pilot mumble….

Legagneux’s first run was a short test, flying just 300 meters and reaching only 3 meters of altitude. With that success, Legagneux then flew three more times. On the fourth, he set out to fly to Gärdet to see firsthand the site of his upcoming demonstration. After just 2.5 kilometers, he abandoned the trip and had to put it down. He chose a field near Kaknäs which turned out to be a military shooting range. Unexpectedly, he collided with iron bars that had been set out in the grass. Repairs were made by local carpenters from Ekstrands Snickerifabrik and he reported to the Swedish Motor Club his readiness for the official “first flight” event to come at Gärdet. In the next 48 hours, tickets sold rapidly with the highest prices paid for seats closest to the flight line.

The wind blows hard against me and the rush of air past my ears and the incessant roar behind me is disorienting. How the airship rushes over the ground with increasing speed… Right before us, now just 25 meters farther on, I can see that the ground sinks away suddenly. Ahead, there is a steep drop off. How shall we proceed? How shall we pass it? We shall go over it, up into the air, we shall fly over it!

On Monday, August 2, 1909, King Gustav V, a host of senior officials, the French ambassador and 5,000 spectators gathered in the evening upon the drill field at Gärdet. To the wild cheers of the crowd, Legagneux’s Voisin-Farman rose beautifully. The Frenchman made a slight turn and passed before the castle at Gärdet before heading down the road and into the distance. Not far away, he landed to turn the plane around, calling for help from some spectators at the roadside. In their excitement, however, they tipped the plane forward and damaged the front elevator. There would be no taking off. Cognizant of the crowd and tickets sold for the event, Legagneux taxied the plane back up the road to arrive before the grandstand. The spectators greeted him with applause.

The next day, on Tuesday, August 3, 1909, he would fly again from his tent hangar at the artillery field of Ladugårdsgärde. There, he invited journalist Eric Pallin to come up for a ride. Pallin would write a story of his first flight — his words ring with excitement even today, more than 100 years later as he describes his first take-off:

Aaaah! I am flying! Just before the cliff’s edge, I saw the elevator lift as it angled up against the wind. In that first instant, it was like losing my balance. Like the ground sank away beneath me, and the plane rocked on an invisible swell…. I look down for a moment and regard the ground as it rushes backwards at 60 kilometers per hour. I look up and for a moment I am captured by the sight of Ladugårdsgärde in the morning sun — a beautiful sight — everything is so wonderfully peaceful and still, except for the sound of that terrible engine, as it makes such furious noise behind me.

The elevator flashes yellow in front of me. We rise under a weak updraft. Involuntarily, I regard the way the wing bends like a roof over me, upon its underside the air passes, and our forward motion brings pressures so strong that they carry the machine upward. Now, Legagneux mumbles something like, “c’est fini,” and before I know it, the machine descends, the engine stops and the aeroplane touches the ground and rushes forward a short distance, and then it stops.

I overwhelm M. Legagneux with my ‘Merci.’ He just shrugs his shoulders nonchalantly, then stretches his cramped legs and relights his half-smoked cigarette.

So ended Eric Pallin’s first experience in the air, describing even the casual air of the Frenchman’s flying technique. For us, Eric Pallin too would achieve a historic first. He helped pioneer the artful prose of aviation storytelling and it is on his shoulders that many of us who write of flight stand with appreciation. Lost for words at the experience, Pallin would wax poetic, his words chosen like those of a Shakespeare play. He struggled in those early days to capture and convey that extraordinary feeling of the flying for the first time to an eager readership.

For pilots and aviation journalists everywhere, that feeling will always be remembered. We can all look back at being caught in the magic of flight and the dream of flying like birds. And we all know that once you have flown, you become someone else, reborn to a new world.

One More Bit of Aviation History

After his demonstration flights in Sweden, Georges Legagneux returned to France. There, he took part in the 1910 Air Meet, suffering another crash in his airplane. Over the next four years, he became a well-known and respected name among early aviators. He set several altitude records, reaching 3,100 meters in 1910 and then 5,450 meters in 1912. Sadly, he perished in a plane crash at Saumur, Maine-et-Loire, France, on July 6, 1914, just before the outbreak of the Great War (World War I).