Published July 30, 2012

“Why not go up there?” the journalist Paul du Bochet asked.

François Durafour considered the proposition of a landing on the highest slopes of Mont Blanc, but then he replied with feigned nonchalance, “Why not? It is something that we will study eventually….” Yet despite his casual tone, Durafour was completely taken with the idea. As a Swiss aviator and veteran pilot, he could think of no other who would take the risk. It would require flying to altitudes rarely attempted, and then to land there in the snow, on the slopes just short of the peak — and to take off again from those heights, a challenge far greater than anyone could imagine….

François Durafour’s Greatest Exploit

On this date in aviation history, July 30, 1921, François Durafour would achieve a heroic first. In fact, his achievement was so daring that it would not be repeated for another 30 years and only then with a far more powerful aircraft and better preparations. It had taken months of planning after a first attempt with a passenger aboard his Caudron G3 biplane, an ex-bomber design from the war. In that earlier flight in the autumn of 1920, Durafour had failed, having flown circles just a few hundred feet short of reaching a plateau upon which he might have landed. The press had not been kind in its reports.

Others would have tucked their tail between their legs and moved on, yet Durafour only redoubled his efforts. He was no stranger to pioneering aviation exploits — indeed, the Swiss pilot had been the first span Central America (despite being Swiss!) and had toured New York and set records in Europe. When the Great War broke out, despite Switzerland’s neutrality, he had joined with ten other Swiss who had trained and learned to fly in France, as he had done — together they would form the Swiss Squadron. No mountain would easily defeat a Swiss man and certainly not a man like François Durafour.

“I decided then to restart anew, all alone this time in order to reduce the weight in the aircraft, but as the season was already well advanced toward winter, it forced me to delay until the following summer. The preparations for this next flight would be more carefully planned and not in the least because I prefer this time to remain very quiet, so if unsuccessful, the matter would go unnoticed.”

He researched elevation and relief maps of the mountain’s slopes and selected the Dôme du Goûter on the high western slopes of the Massif de Mont Blanc. His landing would be at an altitude of 4,331 meters, only 470 meters short of the summit. Over the winter months, Durafour modified his Caudron G3 for the flight. In place of the 80 hp rotary engine, he installed a more powerful, nine-cylinder, 120 hp engine. In addition, René Vidart, a fellow pilot, offered him a special propeller that provided better performance in high altitude operations.

When he considered himself ready, he commented, “I have now the airplane for it, but no notion of what it takes to fly the mountains.” Indeed, he was not a mountaineer himself and his plane still carried its regular tires — he did not even mount skis on the plane for the snow-capped Dôme. Finally, on July 30, 1921, he was ready — or as he said, “I decided to attempt the impossible.”

The Flight and its Uncertainties

The day before, his four friends climbed to a high camp in a sheltered spot so as to be able to make the landing spot before his scheduled morning arrival. Among his friends was Georges Werron who would have the job of waving a large Swiss flag to point out the cleared landing spot. To make the scheduled landing, the team left the shelter at 3:00 am and started upward through the last vestiges of a storm that had come through. Yet the weather delayed their efforts. Short of the Dôme du Goûter, the team heard the telltale sound of the Caudron’s engine and watched it pass overhead to cross the ridge and disappear out of sight. For a short while, they could hear the engine, but then suddenly, there was just silence. They rushed upward in the thin high altitude air, had Durafour crashed or made a safe landing? They knew that mountain was crisscrossed with crevices and ice cuts and could only imagine the worst.

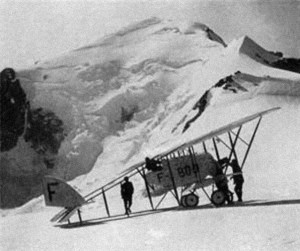

Reaching the Dôme du Goûter, they beheld the Caudron sitting peacefully, angled upward against the slope. Indeed, Durafour had been lucky — the plane’s peaceful appearance belied the fact that it was only with his expert touch on the controls that he had managed to somehow cross over an ice crevasse and not overturn the plane into a wreck. Durafour was standing alongside already accompanied by several others. By coincidence, another group of climbers had been higher up on the mountain that day. Seeing the plane land, they had come down to investigate.

One of the men who had witnessed Durafour’s landing carried a camera — a good thing because as Durafour soon learned, his own cameraman had canceled out. To certify the feat, he gave Durafour his card upon which he had written these words, “I, Henri Brégeault, general secretary of the French Alpine Club, have photographed François Durafour after his landing at the col du Dome on July 30th, 1921, at 7:15 am; a successful landing in all respects and a remarkable achievement.”

Take Off and Return

With the arrival of Durafour’s four friends 30 minutes later, the men would help in getting the plane turned around and repositioned higher on the slope to face a safe run to take off. Then, with a mighty heave, they got its engine restarted and Durafour made his take-off, nearly coming to grief as the plane lifted off just meters shy of falling into a ravine.

Durafour flew free of the mountain’s grip, circled once around the Aiguille de Bionnassay, and then climbed back over the Dôme du Goûter to wave to his friends below. He then turned and made a circling descent to Chamonix. Afterward, as quiet testimony to the challenge he had faced when taking off, he would say, “If you gave me a million Swiss Francs, I wouldn’t try that one again.”

One More Bit of Aviation History

After so many great exploits, like many early aviators, François Durafour abandoned flying soon after his most triumphant flight. Over the years, many of aviation’s greatest pioneers had pressed the limits one too many times and had died trying to attain one more flight. Even for the luckiest of these early pioneers, the risk of death was always great. Durafour would retire to Versoix to run an automobile garage. Later, he became a French citizen but as a Swiss native, he stayed out of the Second World War. After the war, he would help construct the airfield at Annemasse (his second field, actually — the first being at Collex-Bossy, in the Canton of Geneva in 1911!). He died in Geneva on March 15, 1967, at the age of 78.

Click Here to Watch an Interview with Durafour

(courtesy of Swiss Television; 15:47 minutes) =>