Published on August 5, 2012

The Blériot 110 was a proven aircraft. It’s great 600 hp Hispano-Suiza engine was perfectly tuned. By all accounts, Rossi and Codos were well-prepared. They were skilled at endurance flights and distance records. The side of their plane, the “Joseph Le Brix,” carried a long list of records. Yet such flights were always a gamble. It might be that they would take off from New York and simply disappear over the horizon, never to be heard from again. With a final check, they cast all fears aside and started the engine, the great four-bladed propeller at the nose making huge swings. Their lives had now been placed on the table in the ultimate gamble — a non-stop flight from New York to Rayak, Syria, a distance of 9,104 km (5,657 miles). At what cost, however, should such records be pursued?

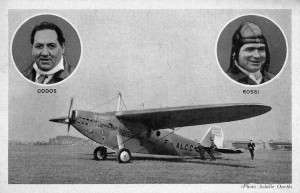

Of the 103 aviation records tracked by the Fédération aéronautique internationale, by 1930 France held 32 of the medals. With this flight, as with all record attempts, France’s status as a leader in aviation were on the line. This was the era the French called, “The Grand Raids.” It was a time when national prestige was reflected in the record books of aviation, when governments measured one another and themselves by the achievements of their industry and aircraft in the skies. Rossi and his Blériot 110 was already a veteran of long duration flight. The plane had been specially designed to order by the French Government for this latest series of record-setting flights. At a wingspan of 26.5 meters and with 7,000 kg gross weight, the 110 had flown closed circuit trials from the airfield at La Sénia, Oran, in Algeria, at the hand of Maurice Rossi and a different pilot, Lucien Bossoutrot. This latest flight to Syria was piloted by Rossi yet again, yet this time with Paul Codos as his copilot.

“The example of our flights has created a sustained movement for private aviation and flying clubs that have sprung up on all sides. Great Oran! Courageous Algerians! How many times I’ve regretted such hard experiences during my wanderings of man flying, but not now,” Rossi had exclaimed after his first record flights in the Blériot 110.

Such records were made to be broken too. This was a lesson that Rossi and Codos had learned all too well. Rossi’s first record flight in the Blériot 110 had achieved a distance of 8,822 km over 75 hours and 23 minutes in the air. His celebrations, however, were cut short when another pair of Frenchmen, Louis Mailloux and Jean Mermoz, piloted their Bernard 80 a distance of 8,960 km with 59 hours and 13 minutes aloft — a faster plane with greater range as a result. Between November 1930 and March 1932, Rossi and his copilot Bossoutrot tried eight more times to set world records for distance on the closed circuit over Algeria. In 1932, they had taken the record back, flying from March 23th to the 26th, 1932, over a distance of 10,601 km, which they achieved in 76 hours and 34 minutes.

Yet these were closed circuit flights in the clear weather. The record Rossi truly desired was prohibited, a straight line distance that would go nearly one third of the way around the globe. After the loss of the purpose-built Dewoitine D.33s on just such a record attempt, the Government of France had placed a ban on straight line flight record flights. Finally in 1933, the government relented and even offered 1 million French Francs to whosoever set the new record. Thus, the two Frenchmen and their Blériot 110 made their way to New York by ship with the plane packed in crates. On arrival, they readied for the record flight, wasting no time.

Today in Aviation History — The Flight Begins

With flight plans filed, the pair took off from Floyd Bennet Field on August 5, 1933. It would be a grueling flight — perhaps less a test of the airplane and technology than the endurance of the two men, who would fly in shifts, resting while the other piloted the next leg. The flight would take more than three and a half days, during which time the plane’s single Hispano-Suiza engine would have to run steadily and without fault to pull the huge bulk of the Blériot 110 through the air to victory. Along the way, they would face weather, navigation challenges and periods of uncertainty. As if a reminder of the risks, soon after take off the Blériot 110 entered thick clouds, a continuous overcast — they would be flying on what few, rudimentary instruments they had, by feel and by compass alone. The plane had fuel aboard for over 75 hours of flight. They would need every drop to make it to Syria.

After a day and a half, they made landfall at Cherbourg, France. Continuing on, they rested more easily. The early part of the flight had been exhausting — almost all of it in the clouds, navigating only by time and speed, holding a heading with no knowledge of the winds. With the their arrival in Europe, they no longer risked an ocean ditching and unlikely rescue if the engine failed or if they were forced down in the weather. Now htey pressed on with their spirits rising. They made a low pass over Le Bourget to celebrate, symbolically linking once again the cities of New York and Paris. After 33 hours, 40 minutes, they overflew Munich. They turned southward and proceeded to Rhodes, enjoying better weather. Finally, over the French trust country of Syria, they elected to set the plane down at Rayak.

The pair’s safe arrival was celebrated across Europe. Once again, Maurice Rossi and Paul Codos would be superstars of French aviation — at least for a short while….