Published on August 28, 2012

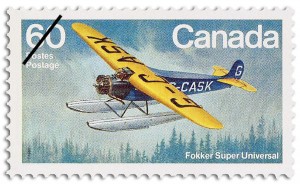

In these days of GPS, radar, radio, and a fully developed airspace system, we often forget of the pioneering efforts of those who flew into previously uncharted territories, across seas and beyond the horizon to get us to where we are today. Often, these men (and women) pushed the limits too hard or too far. Sometimes they didn’t come back. Other times they would fly into the unknown and somehow, against all odds, return to tell the tale. Those were the days of the pioneers — and in many ways, there was no place more wild, more uncharted, more unknown and more difficult than the northern reaches of Canada’s Arctic lands. One of the first pilots to conquer those lands was nothing less than the finest, if stereotypical early aviator, and his name was Punch Dickins. This is the story of Punch Dickins and one of his most daring flights aboard the Fokker Super Universal G-CASK — a twelve day journey across the vast Barren Lands of the Northwest Territories that began today in aviation history, on August 28, 1928.

One of Canada’s Greatest Pilots

Punch Dickins, or more formally Clennell Haggerston Dickins, was a Canadian bush pilot who first flew as a pilot at war on the Western Front in France in 1918. Initially, enlisting as an infantryman with Canada’s 196th Western Universities Battalion, after a year serving as a clerk, he joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and learned to fly. He was then transferred to the RFC School of Instruction located at the Acton Aerodrome, near London. In May 1918, he was transferred to a combat unit, No. 211 Squadron, and flew an Airco DH-9 bomber from Petit Synthe, France. He was credited with not only being a successful bomber pilot but also in becoming an ace, receiving an award of the Distinguished Flying Cross, and being officially recognized with seven kills of an enemy aircraft that had attacked his bomber over the course of 73 combat missions (in turn, he credited his expert gunner, 2nd Lt. Jock Adam, instead with the kills). Clearly, he was an expert pilot.

After the end of the war, he became a commercial pilot and a certified “Air Engineer”, achieving both ratings in 1921. He flew for Western Canada Airways, including on their mail flights, often flying in difficult weather and without support. By 1924, he enlisted in the new Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), in which he flew until 1927. Returning to a private life outside of the military, he became a bush pilot flying of Canada’s remote territories. It should be noted that during the early years of the RCAF, a major function of the aviation service was the charting of Canadian territories, including by aerial mapping through photography, and thus many RCAF pilots were effectively already bush pilots based on their skills and experience.

Where other bush pilot would have been perfectly satisfied with flying local runs to and from hunting towns and distant camps or taking fisherman into the wilds of Canada’s northern territories for the money, Punch Dickins instead set out with the higher ambition to pioneer the vast territories known as the Barren Lands of the Northwest Territories. Therefore, he acquired an aircraft suited for the task, a Fokker Super Universal with the registration G-CASK, and planned a 12 day journey into the wild.

The Fokker Super Universal

Punch’s Fokker Super Universal, registration number G-CASK, was designed and built in the United States. It was a new design, having made its first flight in March 1928. The basic Universal model cost $14,200 new — the Super Universal cost more than that. The plane was a rugged design with a wooden wing, steel tube frame and fabric covered fuselage and control surfaces. The controls and wires were overbuilt and external to the fuselage and wings, making for easy inspection and maintenance. The landing gear were large and rugged with bungee cord shock absorbers that allowed pilots to land on unprepared strips, in the rough, on river banks, and in fields with confidence that the undercarriage would not collapse.

In terms of performance, the Fokker Super Universal was stable, reliable and enjoyed a reasonable range — roughly 680 miles. A pair of fuel tanks in the leading edges of the wing combined to offer a capacity of 78 gallons. It was equipped with a 450 hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp B radial engine. The cargo compartment could carry nearly 500 pounds plus full fuel and the pilot. Whereas a standard Universal had the pilot sitting atop the fuselage in an open cockpit sitting above a passenger/cargo compartment that was sealed from the winds and elements below, the Super Universal brought a key advantage to Punch Dickins that was essential to flying the cold of the Arctic — it had an enclosed cockpit for the pilot. Finally, it could mount floats, wheels or skis, making it perfect for all seasons and environments. In fact, the Fokker Super Universal was a perfect bush plane for the Canadian north — and indeed it was the perfect plane of the time for pioneering flight anywhere. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Fokker Super Universal was selected also by Robert Byrd for his Antarctic exploration flights (also in 1928).

Punch’s Pioneering Flight

Equipped with the right plane for the task ahead, beginning on August 28, 1928, and for the next twelve days, Punch Dickins ranged over the Barren Lands, covering and charting the territories from his float-equipped Super Universal. Its wings were painted in bright yellow and the fuselage in dark blue while its floats were in silver. On the flight with Punch Dickins was Bill Nadin who, like Punch, was a certified mechanic. A Canadian named Colonel C. D. H. MacAlpine came as a passenger and observer. Along the way, they met with supplies that were brought ahead by boat to Fort Smith, including (famously) by the paddle-wheel steamer Northland Echo, a ship operated by the Hudson Bay Company and captained by Colonel J. K. Cornwall, also known as “Peace River Jim”.

Once beyond Fort Churchill, the flight was beyond the knowledge of man and into veritable “terra incognita”. Punch flew without maps — there were none — making his own maps as he went and then retracing his route. He flew rivers and mountain ridge lines, charting lakes and forests across the Barrens as he flew. His plane was beyond the edge of human reach, without a radio and into lands so far north that his magnetic compass readers were inaccurate. Sometimes, he flew by the sun.

In all, Punch Dickins and his crew covered a total of 3,956 miles, much of it never mapped or seen from the ground, much less from the air. He averaged about 330 miles per day on his quest — but that is only if one discounts the days he had to tie down and await the passage of bad weather. On flying days, he was aloft up to five hours at a time. He carried the fuel he needed in the cargo compartment and, with the help of Bill Nadin, performed all his own maintenance during the flight. With a cruise speed of approximately 100 mph, Punch’s twelve day journey involved more than 40 hours of flight time. For all intents and purposes, it was the 1920s equivalent of flying to the moon — once out there, they were on their own. Whatever supplies they brought along were all they had, though they could supplement their food by hunting and fishing during stops along the way.

Afterward and Awards

Not long after his return, Punch Dickins was notified that his pioneering aerial exploration of the Barrens would be honored with the award of the McKee Trophy, also known as the Trans-Canada Trophy. It would prove to be a fitting reward for a true pioneer of Canadian bush flying. Nonetheless, this wasn’t to be his only great pioneering flight. He would go on to map yet more of the Arctic, fly thousands of hours of the wild north in all weather and conditions, and truly embody what it means to be a “bush pilot”. The best estimate is that over the years he flew more 1 million miles of uncharted territory. Among his later achievements is a flight that mapped the McKenzie River from its source to its end. Year after year, he dedicated himself truly to expanding the horizons of Canadian aviation and enhancing Canada’s understanding of its own country. Even after retiring from bush flying, Punch continued to fly until he was 78 years old. He finally passed away in 1995 at the age of 95.

Ultimately, the Canadian government recognized Punch Dickins as one of the “most outstanding Canadians” of that nation’s first century. He was inducted into the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame with these words: “Despite adversity, he dramatized to the world the value of the bush pilot, and his total contribution to the brilliance of Canada’s air age can be measured not only by the regard in which he is held by his peers, but by the nation as a whole.”

One More Bit of Aviation History

In the 1930s, Punch Dickins flew his Fokker Super Universal G-CASK to bring a mineral prospector named Gilbert Labine to Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories. Once there Labine went to work examining the rock formations and looking for minerals of value. He chanced to discover “the richest deposit of pitchblende in history.” What is “pitchblende” you might ask? It is the colloquial name for the Uraninite, an ore that contains high levels of the element Uranium. Ten years later, the pitchblende of Great Bear Lake would be mined for a very special wartime effort — the Manhattan Project. Ultimately, it would be the Canadian uranium discovered by Gilbert Labine with the help of Punch Dickins that would be used in the two atomic weapons that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What were the four aircraft that (at least in the eyes of the Canadian government) were the true pioneers and most noteworthy of bush flying in the Arctic north?

The four aircraft that were the pioneers of bush flying in the Arctic north were:

— Fokker Super Universal

— Fairchild 71

— Noorduyn Norseman

— de Havilland Beaver