Published on August 30, 2012

For the life of me, I cannot see what an aeroplane can do which is likely to be of any practical utility in warfare.” — Comte Henri de la Vaulx, France, 1908.

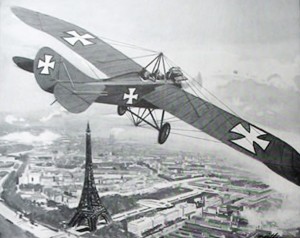

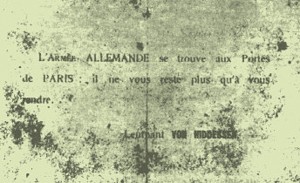

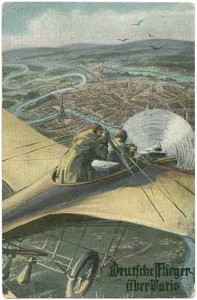

Today in aviation history, on August 30, 1914, a German military pilot, Leutnant Ferdinand von Hiddessen, took off with an observer in his two-seat Taube airplane on a very special mission — to drop bombs and leaflets on the enemy city of Paris. His flight marked the dawn of a new era in aviation history, one that began with the Great War of 1914. To arrive over Paris, Lt. von Hiddessen had pressed his fragile Taube to the limits. Flying at 5,500 feet above the streets of Paris, he had fuel enough to fly lazy circles for 30 minutes as he gazed on the city below. In the back seat of his plane, his observer scanned for possible targets — he spotted a railway station at the 10th arrondissement. Far below, Parisians paused to look up at the small airplane high overhead. Climbing to about 6,000 feet, Lt. von Hidesson took the first bomb from the makeshift rack mounted beside his cockpit. It was one of four 5 pound handheld bombs that he had brought along. He carried also a small sack of sand to which was affixed a six foot German pennant and a satchel filled with printed messages that read, “The German Army is at your gates — you can do nothing but surrender.” This was to be his fifth bomb — a propaganda weapon that it was hoped would cause the French to panic and surrender en masse. At precisely 12:45 pm, he dropped the first bomb.

“…Certain facts have emerged from the fog of war which will assist us somewhat in appraising the work and value of aircraft. Such of these facts as have become known are, it must be admitted, not of decisive importance, and it will not do, therefore, to attempt to base any definite judgment upon them. In the main, the records are simply those of isolated acts on the part of individuals which have not had any real effect on the issues of battles. So far as concerns the correlated work of aircraft to the larger aspects of the vast operations now taking place on the Continent of Europe, we still remain absolutely in the dark.” — Flight, No. 297, No. 36, Vol. VI., September 4, 1914

Of the bombs that Lt. von Hiddessen dropped, we know the precise impact points of three — his second bomb fell into a courtyard at 107 Quai Valmy, a building that was used as a home for the elderly. His third bomb landed on the street at 66 rue des Marais. His fourth bomb came down through a skylight at No. 5 and 7 rue des Récollets — it failed to detonate.

Throughout the flight to Paris and afterward on his return back to his base, Lt. von Hiddessen’s primary concern was not whether he would be shot down by an enemy aircraft — fighter planes were not yet conceived of. The concept of the fighter plane was not yet born — he was safe at least from that risk. He was more concerned that his fragile plane’s engine would last the duration of the 2 and a half hour flight back to rejoin his unit, the 11th Military Group, at its airfield beside St. Quentin. Some pilots had returned from the battlefields with reports of being fired upon by the ground forces. Others told of shooting at one another with handguns while aloft. There was even a rumor of an event four days earlier one pilot rammed another aircraft — that rumor was true; both men fell to their deaths.

Just five days before Lt. von Hiddessen’s mission, on August 25, the first aerial victory of the war was achieved when Lt. Harvey-Kelly and two other airplanes of No.2 Squadron RFC forced down a German Taube — none of the planes had weapons aboard.

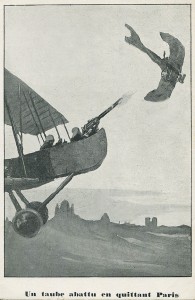

“Then, the Germans seem to be employing aeroplanes in their campaign of terrorising peaceful civilians, for several of these craft have flown over Paris and dropped bombs on hospitals and other non-military buildings, though the damage done appears to have been comparatively slight, and there is reason to believe that the marauders were made to pay the extreme penalty for their audacity, for they were chased by superior numbers of French aeroplanes, and in the words of the official despatches “were probably overtaken and destroyed.”

Such reports were patently false. No French airplanes had intercepted Lt. von Hiddessen’s Taube and the claim that the German airplanes (there was only one) “were probably overtaken and destroyed” was mere propaganda. One plane had bombed Paris and Lt. von Hiddessen had returned back to St. Quentin successfully. Likewise, the word about him bombing hospitals was just the French attempting to lionize their enemy and stir public anger and greater support for the war effort.

“This much may be gathered, however, that aircraft as a means of attack have not been conspicuously successful…. So far as we are able to go, it appears that the opinions have expressed consistently, long before the war broke out to confirm or confute theories, that the main use of aircraft in war must be for reconnaissance, and not for offensive operations have been fully confirmed by what has actually happened.”

Sadly, Lt. von Hiddessen’s raid on Paris was a harbinger of what was to come. He had dropped all his bombs in quick succession. At the quai de Valmy, his bombs had killed one woman and injured two bystanders. The city was so vast that he could hardly miss it, yet equally that same vastness also meant that his aerial bombs could affect nothing in the larger war. As for his propaganda leaflet drop — the first such in history (thus, he achieved two firsts that day) — Lt. von Hiddessen would drop the entire sack at once rather than tossing out handfuls of leaflets. Thus, the sack was retrieved intact and unopened, whereupon it was brought to the police for examination.

The Germans would fly raids for several weeks afterward, dropping more bombs and more leaflets, all with little effect. As the pilots grew accustomed to the route, they made the mission a regular routine — even arriving at the same time each day. It wasn’t long before Parisians called the planes, “the six o’clock Taubes” after their punctuality. The German magazine Flugsport on October 28, 1914, carried two of the other messages that were dropped on Paris during this time. One read, “Frenchmen: You are being deceived. The Germans are victorious. Beware of the Englishmen and their insincerity.” The other stated,”We have conquered Antwerp. Soon it is your turn.”

In modern terms, Lt. von Hiddessen’s bombing attack and those that followed were tactical failures. Yet to measure the raid solely that way would miss the point. Lt. von Hiddessen’s effort had established a new understanding of the potential of air power. A line had been crossed. In December, another flight of Taubes reached Dover, England, and dropped yet more bombs. By 1915, raids against towns and cities were commonplace. In later years, leaflet drops would become key tools of psychological warfare campaigns. Just as airplanes would be transformed in performance, so too would the theory of aerial combat advance rapidly. Each side’s warplanes would go from being unsteady, underpowered reconnaissance machines to new and deadly tools of war.

The world would not be better for it.

One More Bit of Aviation Trivia

As with many early war aviators, Lt. Ferdinand von Hiddessen had learned to fly in the relaxed time of the Belle Epoch’s final years. In von Hiddessen’s case, he had qualified on a Euler biplane on January 27, 1910, earning License No. 47 in Germany. Yet while others were civilians enjoying the dream of flight, Lt. von Hiddessen was a soldier. He had joined the Germany Army and served with the Dragoons (2nd Grand Duke of Hesse), in Darmstadt starting in 1908, rising to the rank of an officer. To him, the airplane was the future of warfare. After his bomb attack on Paris, Lt. von Hiddessen would continue to fly combat missions until he was shot down over Verdun in 1915. Somehow, he survived and would spend the rest of the war in captivity in France. After the war, he returned to Germany and became active in politics in the late 1920s. He rose to become a Parliament minister with the SA in Hitler’s Nazi Reichstag in the years prior to the outbreak of World War II. He survived the Röhm-Putsches, World War II and the difficult times afterward, finally passing away on January 24, 1971, in Neustadt in Germany’s Black Forest.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Lt. von Hiddesson’s bombing raid was the first against a city — yet what was the first bombing raid against a non-urban target, where and when did it take place, and who flew it?

From a balloon: Austrians against Venice, 1849 — but that was a city. Non-urban (and from a heavier tha air aircraft): Italo Turkish War, 1 November 1911. Pilot: Giulio Gavotti. Airplane: Taube, Target: Turkish military forces at the Tagiura Oasis and an Ottoman military camp in Ain Zara, Libya.