Published September 3, 2012

The storm hit at dawn, its winds buffeting the Navy’s airship ZR-1, the USS Shenandoah. Gripped by a massive updraft, the huge aerial vessel was spinning out of control, up into the heart of a giant storm cell. The captain ordered his crew to vent helium, but then she was spat out again and plunged earthward. Somehow, the crew regained control, leveled out and tried to turn southward out of the storm. It was not to be. Once again the storm took hold of her and almost instantly, she rose to 3,500 feet of altitude. Then with a violent twist, the updrafts tore the Shenandoah in twain. At first, the center section and tail both fell together, then they too were ripped apart and dragged down by the weight of the motors. From the bow, Lieutenant Commander Charles E. Rosendahl, the navigator, saw the control car fall off the bottom of the airship with seven men inside, including the airship’s captain and executive officer. Then his piece careened upward, lifted by the storm and buoyed by its still intact helium gas bag. Amidst the chaos, Rosendahl called out his first orders to the seven men trapped with him in the nose of the shattered airship. If they could vent enough helium, they might be able to escape the deadly grip of the storm and get down safely — it was a slim hope.

About the USS Shenandoah

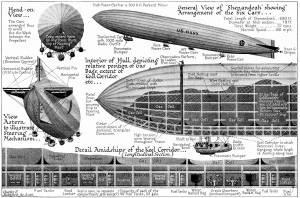

At 682 feet in length, the airship USS Shenandoah (an American Indian word meaning, “Daughter of the Stars”) was the pride of the US Navy. Built in the United States, the airship was a close copy of the L-49, a captured German Zeppelin from the Great War of 1914-1918. The crew was experienced and most had flown the airship since it was commissioned almost exactly two years before on September 4, 1923. Since then, the Shenandoah had made 56 flights. Many had served the higher purpose of showing the Navy’s banner to the public across the landlocked interior of the United States, helping to build political support for the Navy’s programs. The Shenandoah was a natural public relations tool — a great battleship of the skies, the silver bullet-shaped rigid airship was size of three and half of today’s blimps lined up end to end.

Yet nothing could have prepared the Naval crew for this terrible storm, hitting one day into the great airship’s 57th flight. Flying into unsettled weather, the Shenandoah had left Lakehurst, New Jersey, on September 2, 1925, on a mission was to fly a PR tour to a series of state fairs across the heartland of the Midwest. Thus, there was a schedule to keep, even if the weather didn’t cooperate. The airship’s commander, Zachary Lansdowne, was an Ohio native. That morning, he recognized the ferocity of the storm coming, typical of the worst the Buckeye State had to offer. Wisely, he had requested the flight be postponed. The higher ups denied the request, noting that the Shenandoah had flown over 25,000 miles in all weather. The airship would fly since people were expecting them to hold to the schedule. The orders were cut — and the die was cast for disaster.

The Disaster of the Shenandoah

By dawn on September 3, 1925 — today in aviation history — the ship had reached Ohio by flying through the night. The crew could see that they were facing a deadly squall line of storms. Attempting to find a gap, they pressed on, but soon the storms had them. The Shenandoah was not designed to handle the violent updrafts it had encountered. It was a slightly lengthened copy of a captured German wartime Zeppelin, a craft that was fragile, carefully engineered, and designed for high altitudes — it was a lightened ship for wartime circumstances. That fragility had been translated into the Shenandoah’s structure. When the storm had torn the airship apart, the tail and center section had fallen away — yet with seeming impossibility, some of the men aboard those pieces would survive. All Lt. Cmdr. Rosenthal knew was that his section, the remaining bow piece, was still aloft.

Answering his shouted orders, Rosendahl’s men reported in. The circumstances were grim. They had an intact gas bag and one working vent valve; the valve line was in hand. They had a working ballast tank too, filled with 1,600 pounds of water. The bow section had no engines, so they were reduced to free ballooning. And they were rising upward again into the heart of the storm cloud. Yet before they could try to save themselves, there faced another pressing emergency. Lieutenant Joseph B. Anderson, the airships weather officer, had come up the ladder from the control cab just as it had fallen away — he was the only survivor of that catastrophe. Finding himself dangling over the gaping hole, he was barely hanging onto a single piece of the twisted center catwalk. With an iron grip, he held to a few wires, hoping not to fall as he looked down at the earth thousands of feet below.

Rosendahl summoned some of the men to aid Anderson. A rope was found and they lowered it, but Anderson couldn’t let go of the wires or he would have fallen. Instead, as he held on, they carefully looped the rope around his torso. With a heave, they pulled him aboard. It was a close call, but there was no time to celebrate — Anderson was aboard, but they all still might crash. Rosendahl turned to the problem of somehow landing the bow section.

A Miraculous Landing

At once, Rosendahl ordered the helium vented opened. If enough helium could be let out, the bow section would escape the grip of the storm’s updraft and begin to fall downward. The crew pulled the vent line. It worked and slowly, the upward movement lessened. Then with a sagging feeling, the bow section began to drop, slowly at first, then accelerating downward. Rosendahl waited until they were clear of the vertical wind sheer before he called for some of the water ballast to be dumped overboard. As the water poured out, the bow section continued to hurdle toward the ground below. Somehow, as they neared the surface, the vertical descent slowed. Then the drop halted. They were below treetop level and were being pushed along by the storm’s winds. Directly ahead, they could see a farm.

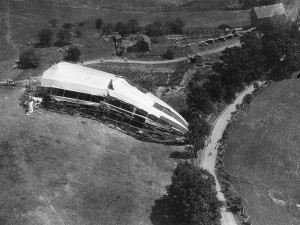

Incredibly, the farmer would wake to a phone call from his neighbor telling him to go outside and look at the sky — an airship was crashing toward his house out of a big storm cloud. Thus, Ernest Nichols stepped onto the porch and looked up in disbelief. As it came past in the storm’s outlying wind, some of the airship’s crew shouted to him, “Take hold!” He ran forward and grabbed one of the dangling wires from the Shenandoah’s bow and quickly tied it off to a fence post. It was no use. The great bulk and momentum of the bow section snapped the post like a twig. Nonetheless, the airship twisted slightly and slid into the roof of Nichols’ shed, shattering it. Next, it crashed into his grape arbor. Sustaining more damage, the stricken bow section leaned downward and hit the ground. They were down.

Escape and the Toll

First to leap off were Anderson and another of the officers. They both ran quickly to tie whatever lines and wires they could find to trees and posts. As they jumped off, now lightened of their weight, the bow section made an attempt to rise again. Even as they continued to vent more helium, the quick-thinking Rosendahl ordered his men to open fire with their pistols into the gas bags. As many new holes appeared, the helium rushed out faster and the bow section once again settled, this time permanently. The last of the men clambered out of the giant bow section that now filled Ernest Nichols’ yard. They had survived a miracle landing, one brought on in large part as a result of Rosendahl’s command of the emergency.

Of the 43 officers and men that crewed the Shenandoah, fourteen had died in the crash. The three pieces of the Shenandoah had crashed across a twelve mile long swath — 29 men survived. Of the survivors, only two were injured. Within hours, hundreds of locals would descend on the pieces of the Shenandoah and strip it clean, even carrying off many of the controls and instruments as souvenirs. By nightfall, the three pieces were nothing more than dismembered skeletons. A full accident investigation would be inconclusive. Much of the evidence of the airship’s structural failure was stripped away and missing.

Aftermath

Public hearings would follow to determine the cause and fault. Predictably, the Navy attempted to blame the airship’s commander for flying into the bad weather, yet his ex-wife, Margaret Lansdowne, would stand up against the Navy’s court of inquiry. Stripped of counsel after being declared a “witness” so as to try and sideline her accusations, she hold her own to clear her husband’s name. Her points that the Navy pressured her husband to fly despite the bad weather drove home. The Navy would persist with its dream of aerial battleships and would launch three more great airships, the USS Los Angeles, USS Macon and USS Akron. All were stronger designs, none as narrow with the pencil-like beauty of the Shenandoah. For enhanced safety, they too used helium. Yet in the end, one by one, these great airships would also crash, spelling the end of the Navy’s rigid airship vision. In the end, the Navy opted for hundreds of more flexible, nimble and smaller blimps rather than a few huge airships — but that is another story….

One More Bit of Aviation History

Lt. Cdr. Rosendahl remained a staunch advocate of rigid airships for the rest of his career. Staying in the US Navy and reaching the rank of vice admiral at retirement, Rosendahl emerged from the disaster as one of the Navy’s new generation of airship experts. He was a staunch advocate of lighter than air programs and, after commanding the USS Los Angeles for a time, helped the Navy transition to blimps. As commander of Lakehurst, he watched the fiery end of the Hindenburg. During World War II, he commanded the heavy cruiser USS Minneapolis (CA-36). Off Guadalcanal, his ship was torpedoed during the Battle of Tassafaronga, yet made it to safety at Tulagi due to Rosendahl’s calculated judgment and calm command of the emergency. It was an action for which he was awarded the Navy Cross. At Tulagi, the ship arrived missing 80 feet of it bow. Afterward, he returned to blimps as a rear admiral, serving as chief of the Airship Training Command. Even after retirement, he pressed unsuccessfully for the rest of his days for a return to great airships of the past.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The German Zeppelin L-49 was a high-flying, fragile craft. Where and how was it captured?

In October, 1917 the German crew on Zepelin L-49 was overcome by altitude sickness. The airship was escorted to a landing in France by French pilots and captured.