Published on September 21, 2012

Nobody knows exactly what date she first flew, though it was likely sometime around September 21, 1908, soon after her arrival in Italy. She was an unlikely candidate to be the first woman to solo in the history of heavier-than-air powered flight, as Thérèse Peltier was a French sculptress from Paris. She was in love with another popular sculpture artist of the time, an itinerant aviator named Léon Delagrange. Through his enthusiasm for flying, she was introduced to aeroplanes.

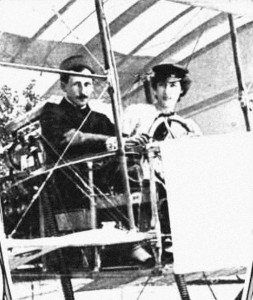

She was first photographed posing with Delagrange’s Voison boxkite at Issy-les-Moulineaux near Paris on September 17, 1908. Thereafter, the two traveled to Italy together — a second trip together. On the first trip, Delagrange had done what was then considered unthinkable — at Turin, he invited her to fly as a passenger in his aeroplane. She too did the unthinkable when she graciously accepted the offer. They flew together, even if it was a short “hop”.

First Flight as a Passenger

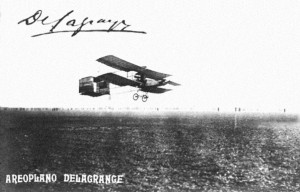

Back in France, Delagrange asked her to accompany him in his Voison boxkite for a record-setting endurance flight — again, she agreed, and this time they were aloft for 30 minutes and 28 seconds. A month later, they traveled south again together to Italy. Delagrange flew in exhibitions around Italy, including a flight in Rome. For her part, Peltier wrote about her experiences for the newspapers back in France. It was then that she decided to learn to fly an aeroplane solo.

At the time, it was thought that Thérèse Peltier was the first woman to fly on an aeroplane, even as a passenger. Later, it was realized that in the end of May, Henri Farman had taken up another woman first, a Belgian named Mlle. P. Van Pottelsberghe while Farman was visiting in Ghent. Yet where the Belgian woman was content with her one brush with the freedom of the air, Thérèse Peltier was captured by the magic of flight.

In Italy for Exhibition Flying

After her first passenger flight, Thérèse Peltier stayed with Léon Delagrange in Italy for a time. Exactly what they were doing is unclear, though it was probably a combination of a summer break to the south with the intention for Delagrange to fly a series of exhibitions. It appears to have been a relaxed trip and the late summer Italian sun and air made for a fine vacation with inspiration in the sights, the foods and the atmosphere of La Bella Italia.

During this time, Peltier observws each flight Delagrange took. She flew with him as a passenger a multiple exhibitions and absorbed all aspects of aeroplane control. This was the best way a new pilot could learn in those days, just by sharing experiences, and discussing the basics of flight control. She learned too how the engine and propeller worked and got used to the “feeling of flight”.

The First Flight

Preparing for her first solo flight was rather haphazard. By modern standards the sort of instruction she received would be considered little more than a case of “the blind leading the blind”. Delagrange was no expert and each flight he did was dangerous. In those days, there were flight schools, however. There wasn’t even a ground school, nor even standards. You watched how someone flew, talked about it, and sat in the cockpit while the “experienced” instructor pointed out the various wheels and controls, and when you thought you were ready, you tried to fly solo. If you survived to land, you’d soloed and were considered a pilot.

Aeroplanes were dangerous and often unstable. They were not reliable. They were underpowered too. Even an experienced pilot could be surprised by the unexpected. Many early aviators did not survive more than a few years. Most died within months. Looking back on it, it is hard to imagine that the early pioneers thought it was worth trying — nine of ten early pilots died.

For Thérèse Peltier, the date of her first solo took place as the weather cooled in mid-September. In the military square of Turin, the machine was made ready. She would take off and fly a straight line and then land — there would no attempt at turning the machine. She succeeded and flew 200 meters ahead in a straight line. She never rose more than 2.5 meters above the ground before setting the machine back down. Her aeroplane was Delagrange’s Voisin boxkite, a plane that carried no ailerons or wing warping. To turn, it skidded around flatly on the basis of rudder input alone. She had not yet conquered the art of steering.

Never Registered or Certified

A week after her first solo, the Italian magazine L’Illustrazione Italiana published news of her achievement. The magazine ran a brief story in their September 27, 1908, issue in its weekly, regular publication. How often the two flew thereafter is not clear, but it is likely that she flew only rarely during the following year and a half, both in Italy and then back in France.

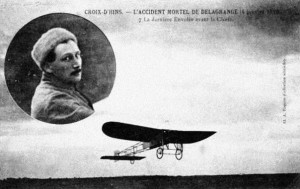

On January 4, 1910, tragedy struck Léon Delagrange. While flying in his new Blériot aeroplane, he suffered a fatal accident. He crashed at Bordeaux. Thérèse Peltier was one of the first to run over. Along with Delagrange’s mechanics, she pulled his corpse from the wreck. She was overcome with grief.

She described the terrible events of that day in a letter she wrote to Henri Deutsch-de-la Meurthe, one of the key sponsors of aviation in the early days:

“I am mired in my grief, lost, and devastated. We were from the same country, Leon and me. We had known each other as children. And for twelve years, despite everything that should have separated us, we had never left each other…. He was my childhood friend, my master of art, my strength, and my balance in life. I was ambitious, ardent in life. Everything seemed beautiful, interesting, and cheerful because he was there and he loved me and I leaned on him. And now there is nothing, nothing at all. The earth seems like a black hole. I feel that I struggle as if I am in prison. Consider that he fell in front of my eyes — far away though, but when I got him, I found he was but a corpse. There was no one there, neither friends nor relatives. And his mechanics and I laid him to sleep in his coffin — just us, alone.”

Despite that she could have easily applied for formal certification by one of the Aero Clubs of Europe, she never did. She gave up on flying for the rest of her life. Her choice to abandon aviation probably saved her life.

That choice does not diminish her achievement in any way. Every woman pilot since has followed her into the skies. One step at a time, women conquered the air — just as men did.

She was a true pioneer in every respect.

One More Bit of Aviation History

At the time of his last flight, Léon Delagrange had been flying in the first Blériot aeroplane to be fitted with a 7-cylinder Gnome Rotary engine. For some reason, as he made a turn at the edge of the field, his wings simply folded back from the fuselage. The plane dropped vertically into the ground. He was killed on impact. He was just 37 years old. Two years later in 1912, Louis Blériot discovered the flaw in his wing design that had caused the crash. By then, several other crashes had taken place in the same circumstances. One other pilot, George Chavez, had also lost his life when his wings had folded in the same way. With the problem fixed, the Blériot would go on to design a series of aeroplanes that were considered the safest in the world.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Why do some consider Mrs. Hart O. Berg’s flight under the tutelage of Wilbur Wright at Le Mans in October 1908 to be the first “real flight” by a woman?