Published on October 6, 2012

In Israel 39 years ago, it was Yom Kippur, the most holy day of the Jewish calendar. The roads were bare of traffic, businesses were closed and many were at home or at synagogues in prayer and fasting. Likewise, the Arab world was celebrating the holy month of Ramadan. In the days leading up to the fateful events of October 6, 1973, there were warning signs of possible war. As the sun set in Israel on October 5th, General Ariel Sharon was shown the latest reconnaissance photographs of Egyptian military exercises. Seeing that forces had massed to unprecedented levels with extensive bridging equipment to cross the Suez Canal, Sharon declared unequivocally that an attack was imminent. Other Israeli officers concluded the same thing.

Meanwhile, nearly a dozen intelligence sources, including a highly placed Mossad source (Sadat’s own nephew), confirmed that Egypt and Syria were to attack within the day. In the days leading up to the war, King Hussein of Jordan, fresh from a meeting with Hafez al-Assad and Anwar Sadat, the leaders of Syria and Egypt, flew secretly to Tel Aviv to pass on word that war was planned within days. For Israel, the defense of their nation fell to the Israeli Air Force and its newly integrated F-4E Phantom and A-4 Skyhawk fighter planes provided by the USA.

Yet it is not recounted that it was not the IAF that made the first strikes of 1973, but rather the Egyptians whose fighters, bombers and helicopters achieved a successful surprise attack against key IAF airbases and defense points in the Sinai that began at 2:00 pm local time.

Opposing Ground Forces

Meanwhile, analysts within Israel, most notably the IDF’s military intelligence unit Aman, felt that at the earliest, an attack would be launched after sundown that evening or more likely that it would take place sometime within the next 48 hours. With some uncertainty, reserves were being mobilized across Israel, despite it being Yom Kippur. On the ground at the front line along the Suez Canal were just 450 IDF soldiers who were fortified into a series of 16 defense points. At staging points deeper east in the Sinai, just 290 IDF tanks were available to defend. Massed across the Suez Canal were 100,000 Egyptian soldiers with 1,350 tanks and 2,000 heavy guns and mortars. To address the possibility of IDF armored counter-attacks, Egyptian ground forces were equipped extensively with anti-tank rockets. To eliminate the threat from the Israeli Air Force’s fighters and bombers, an extensive Soviet-supplied SAM umbrella was deployed along the banks of the Suez Canal — and the Egyptian advance was planned to remain within the SAM protective umbrella at all times.

Fighter Strikes of the EAF

The opening phase of Egyptian airstrikes were carefully planned. Prior to 2:00 pm, more than 200 Egyptian Air Force aircraft took off from bases near Cairo (including Cairo West, Inshas and Mansoura, among others). Forming into strike packages with precision, at the appointed hour, they made a coordinated high speed dash across the Sinai Peninsula toward their assigned targets ranging across the entire Sinai Peninsula, down as far as Sharm el-Sheikh. The most important were two key IAF airbases, Refidim and Bir Tamada. Other targets included a series of key IDF defense and supply points, including a Hawk missile site that provided Surface-to-Air-Missile (SAM) coverage for Israeli ground forces in the Sinai.

Incredibly, the airstrikes took the Israelis largely by surprise, even if detected by Israeli air defense radars. The IAF, accustomed to enjoying air superiority, failed to launch an adequate defensive force and was overwhelmed by the massive numbers of Egyptian aircraft. Qualitatively, there was no doubt that the Israeli pilots were superior in every respect, although the opposing aircraft were not ill-matched. Soviet-supplied MiG-21s, Su-7s, and MiG-17s raced toward their targets largely unencumbered by the risk of IAF interception.

The Battle of Ophira

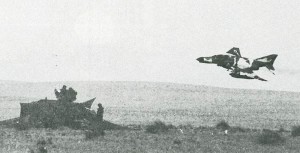

Taking off from the small Ophira Airbase next to Sharm el-Sheikh, a pair of IAF F-4E Phantoms from the IAF’s 107 Squadron intercepted a formation of 28 incoming Egyptian jet fighters — 16 MiG-21s and 12 MiG-17s that had flown in from the south flying at wave height to avoid detection by IAF radar systems. The aircraft were visually spotted by an IAF enlisted soldier named Danny Natovich, who was scanning the skies with binoculars at the time. He reported his sighting to the air defense controllers, who hung up on him the first time after telling him to get some glasses since nothing showed on their scopes. The second report, however, was taken seriously — yet Ophir was a small base that was used for temporary deployments. The only ready IAF aircraft there were just two F-4E Phantoms sitting in underground shelters at the end of the runway. Caught by surprise, the pilots scrambled and launched directly into the teeth of a massive air attack by the Egyptians.

Amir Nahumi later recounted those desperate moments — “I decided to take off – the controller was screaming that there were orders not to take off. However, I decided that the orders were 400 kilometers away and they didn’t know what was going on. I cranked the engine and told my number two to do the same and to scramble as quickly as possible. Standby is very close to the runway so we cranked the engines, went to the runway, and took off. I looked back to see that number two was airborne and that everything was ok, and I saw smoke plumes on the runway, like cotton balls. And I didn’t understand. I told my navigator, ‘Look! What do you make of this?’ He said, ‘They are bombing the runway, this must be war!'”

Among the EAF pilots attacking was Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s half-brother, Atif Sadat. In fact, the IAF fighter planes took off right into the heart of the attack, which rapidly dissolved into an uncoordinated mess for the Egyptians. With the skies full of planes, it was nearly impossible to figure out which were Israeli, while conversely the two IAF pilots found that wherever they turned, they could be confident that they were engaging enemy aircraft. One by one the IAF pilots, Amir Nahumi (with Yosef Yavin) and Danni Shaki (with David Regev), picked off the incoming EAF fighters. Yet it seemed that with each attack, another pair of targets were spotted racing in. At the end of the attack, seven of the EAF MiGs were shot down while both IAF fighters returned unscathed. One of the loses for Egypt was Atif Sadat, who was killed.

Bomber-Launched Missile Strikes of the EAF

Meanwhile, 14 EAF Tupolev Tu-16s took off and made a bold flight toward key targets on the Sinai Peninsula. Using the stand-off launch capabilities of their Soviet-supplied Kelt missiles, the Tu-16s launched and returned to their bases without loss — most of their missiles struck their targets and inflicted heavy damage, though one of the Kelt missiles was intercepted and shot down before it reached its target by an F-4E Phantom flown by Moshe Melnik (with Zvi Tal Aloni in back).

Meanwhile, an additional two Tu-16s took off and flew out over the Mediterranean before turning directly toward Israel and launching their Kelt missiles. Though they were targeting an IAF early warning radar site in central Israel, the IAF did not know that. Eitan Carmi, flying an older French Mirage IIICJ, a veteran of the 1967 Six-Day War, chanced across one of the Kelts as it was speeding along toward Israel. He swooped down to intercept it and shot it down. Luckily, the second Kelt missile fell harmlessly into the sea. For Israel, the Kelt missile assault proved to be greatly disconcerting — most critically, it was apparent that the EAF could strike Israel itself with stand-off weapons against which defenses were thin. The IAF would have to quickly work out a way to neutralize the threat. The Kelt missiles stood as clear warning to Israel that any strike against targets deep within Egypt, would bring a rain Kelt missiles upon Israel itself.

The EAF’s Helicopter Assault

Although the bulk of the EAF’s first surprise attack achieved success, Egypt’s helicopter assault on Sharm el-Sheikh was an unprecedented disaster. The IAF had dispatched additional F-4E Phantoms to cover the airspace at Sharm. With the incoming assault, the IAF’s F-4E Phantoms intercepted the force — all of which were easy targets without effective fighter cover. Elsewhere in the Sinai, Egyptian M-8 helicopters packed with commandos were intercepted by the IAF’s fighter planes. In each case, the helicopters had no escort, leaving them defenseless against the IAF’s fighter planes.

Flying a Nesher fighter, Abraham Gilad shot down two Mi-8s in short order. Likewise, four F-4E Phantoms engaged the EAF’s Mi-8s — and once again, a massacre ensured. Shlomo Egozi (with Roy Manof in the back) shot down five of the Mi-8s. Ben-Ami Peri (with Itzhak Amitai as weapons officer) shot down three. Eitan Peled (Abraham Ashael in back) shot down two. As well, credited with one Mi-8 kill each while flying F-4E Phantoms were Dubi Yoffe (with Oded Poleg), Ran Goren (with Yossi Ye’ari), Moshe Koren (with Ilan Lazar), and Yonathan Ophir (with Avikam Lif). Aboard each of the 18 Mi-8 lost were up to three squads of Egyptian commandos — hundreds of men died pointlessly.

Reviewing the War’s Opening

In all, perhaps as many as 21 EAF fighters and Kelt missiles were downed in the first day of the conflict, including the two Kelt missiles. Thus, the EAF lost slightly less than 10 percent of its attacking force in the first wave. Nonetheless, the EAF’s surprise attack was successful and therefore the second wave was cancelled. The bases at Refidim and Bir Tamada were seriously damaged and taken out of action from the air attacks. Despite the helicopter losses, well over 1,000 Egyptian commandos were successfully deployed at key points throughout the Sinai, where they would fight to delay and undermine Israeli reinforcements and truck convoys for the rest of the war.

The first days of the Yom Kippur War were a desperate time for Israel. The Egyptian Army successfully advanced across the Suez Canal — by midnight of the first day, the Egyptian Army already had 500 tanks across the Canal and many combat brigades. Ten bridges were in place and the onslaught seemed unstoppable. One by one, the fortifications manned by the IDF’s ground forces were overwhelmed and fell to the Egyptian forces with heavy casualties — until only one remained; it would hold out until the end of the war. Israeli armored counter-attacks were beaten back by volleys of well-aimed anti-tank rockets. The IAF’s close air support sorties were effectively countered by barrages of SAMs fired from sites across the Suez Canal. It was soon apparent that two Egyptian Armies were already racing across the Canal at various bridgeheads. Attempts at cutting the hastily erected pontoon bridges by IAF fighters were ineffective and the IAF lost several aircraft and pilots in the effort. What hits were achieved only temporarily disabled the crossing points. The bridges were modular in construction and repairs were quickly effected with new pontoon sections floated quickly into place.

End Game

For the next 18 days, the Yom Kippur War raged while the US and the Soviet Union each undertook massive airlifts of supplies and materiel in hopes of ensuring victory for their partners. In the final days of the war, the Israeli Defense Forces crossed the Suez Canal and, after a decisive victory at the Battle of Chinese Farm, despite heavy losses, the Israeli tanks had pressed toward Cairo and Damascus. Realizing that their capital cities were bare and largely indefensible, the Arab leaders elected to support a peace initiative that the “Great Powers” (primarily the Soviet Union and the USA) had put together in a bid to end the conflict before Russia and the USA themselves went to war. With the conflict winding down, Israeli tanks were within 63 miles of Cairo and within 25 miles of Damascus, though Egypt could still claim that it had achieved its original goals of reoccupying a portion of the Sinai lost in the 1967 War.

In the wake of the Yom Kippur War, the Israeli government and military were forced to reconsider their feeling of invincibility. Reasonably, both sides could be viewed as having won in various phases of the war. A next conflict — if there was one — would likely be another severe test and, while the Arabs could “afford to lose 100 times”, if Israel lost even once, it would spell the end of the state and the people. Five years later, after marathon negotiations under US auspices, the Camp David Peace Accords were signed, ending an era of near continuous war between the major Arab states and Israel.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Incredibly, a family on the beach at Sharm el-Sheikh was filming some home movies when the air battle at Ophira was fought. Recently discovered and released through the Israeli media, the film captures some of the fight and the aircraft involved.

Today’s Aviation History Question

Many Arab leaders are pilots, which gives ample testimony to the respect shown to aviators in the Middle East. Of those leaders in countries involved in the 1967 and 1973 wars, which were pilots and who were they?