Published on October 29, 2012

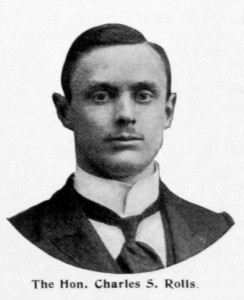

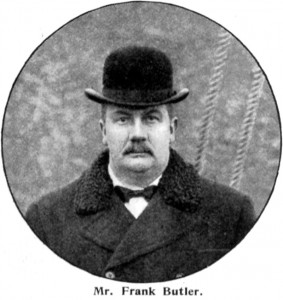

It all began with a car fire in 1901. Charles Rolls and his friend Frank Hedges Butler, along with Frank’s daughter Vera Butler, had decided to undertake a motor car tour around Scotland. As wealthy members of high society and active members of the Automobile Club of Great Britain, it seemed to be a reasonable holiday for the end of summer, in September of 1901, yet things didn’t quite work out right. Vera’s personal automobile (she was a pioneering woman motor car driver) was a Renault 4.5 hp and it accidentally caught fire as they set out. There would be no continuing, even if Charles Rolls and his Panhard (acquired in 1896) as well as Vera’s father, Frank, and his Benz (acquired in 1897) could have made the trip.

To make it up to her father and Mr. Rolls for the unexpected cancellation of their holiday, she had the idea to set up a balloon flight instead. She contacted a pilot named Stanley Spencer to take them aloft. Thus, on September 24, 1901, the three made an ascent from the Crystal Palace in the balloon named “City of York”. As they flew along, they discussed ballooning and the recent success of Santos-Dumont in flying around the Eiffel Tower for the Deutsch de la Meurthe Prize. As the champagne flowed, they considered how the Aero Club of France encouraged that country’s commitment to aviation, noting that Britain was behind in such matters. Then, having left the city of London, as they looked down at the town of Sidcup in Kent, Frank Hedges Butler suddenly offered that they too should form a similar organization, which he envisioned as a sort of an elite social club in London. The others agreed, and so the Aero Club of the United Kingdom was born.

Some weeks later, on October 29, 1901, fully 111 years ago today in aviation history, the papers were filed at Somerset House. The Aero Club of the United Kingdom, Limited, was incorporated.

The Vision of the Aero Club

The original vision of the Aero Club was one that followed the English model — there, over scotch and cigars, sitting together in wood paneled rooms with heavy curtains and tea, aviators and aero-enthusiasts could get together and talk of flying. Members would come during the day and in the evenings to read newspapers and meet with others of high society to discuss matters of interest. For the three founders of the Aero Club, the main interest was ballooning and indeed, this became the primary focus of the Aero Club for its first eight years as it expanded. To help support flight activities, the Aero Club also established an experimental airfield at Shell Beach, on the Isle of Sheppey. For Frank Hedges Butler, ballooning became his central focus and soon he had set numerous records and had flown a balloon from England to France, departing from London and landing at Caen in what ranked as the longest balloon crossing of the English Channel.

With Vera’s influence from the start, the Aero Club was agreed to be open to ladies as well as gentlemen. This decision seemed all the more proper due to the car fire and that it was Vera’s idea of the balloon. Thus, in England at least, ladies were involved in this new venture of flight right from the start. The members soon secured the club rooms, which was achieved with the financial support of the original three founders, Vera, Frank and Charles.

Powered, Heavier-Than-Air Machines

With the arrival of the Wrights at Le Mans in 1908, the Aero Club made its first ventures into heavier-than-air flight. Frank Hedges Butler was one of only two Englishmen to fly with the Wrights at Le Mans. By 1909 the possibilities of manned flight in aeroplanes swept Europe. As ballooning and the arts of flight expanded in England, the Aero Club began to involve itself more and more in matters of safety and regulation. They became the semi-official representative of aviators and began issuing pilot certificates. As well, the Aero Club set up a training school of their own and helped others set up competitive schools. In 1910, the Aero Club was recognized by the King of England and became known by its present title of the Royal Aero Club.

By mid-1910, the shift from balloon flight to aeroplanes was complete, even if the Club would publish balloon and dirigible news all along. The Royal Aero Club’s main publication, Flight, was launched with the new year in January 1909, immediately attracted a wide audience who subscribed and received the newsletter via the post. Boldly, the founders and supporters of the Royal Aero Club put an editorial opinion piece on the front page of every issue. As the RAeC founders and members watched, Britain’s age-old European rivals were soon establishing air forces and training military pilots, yet Britain lagged behind, depending on the admirals the British Navy to keep the island nation safe and secure. The RAeC soon began a long campaign to press the British government to fund a more powerful aviation arm of the Royal Army.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914, the long years of influencing government and military officials paid dividends, allowing Britain to more quickly build a formal and capable air arm. The Great War of 1914 to 1918 was deadly, particularly for airmen, and yet in the end, in November 1918, it was Britain, France and their allies who prevailed. By then, the RAeC had issued over 6,300 pilot certificates.

Post War and into the Future

After the end of the war, the Royal Aero Club returned to its traditional role of promoting commercial aviation, safety and professional pilot training. They sponsored events, helped contribute knowledge and information to critical government policies, and expanding the reach of British aviation pioneers, joining Britain with the farthest reaches of the Empire, to India, to Australia and New Zealand, into Africa and across the Atlantic to Canada. With the sponsorship and shining example set by the Royal Aero Club (and other Aero Clubs in other countries, such as in France and America), the professionalism and safety-oriented field of commercial and private aviation would spread across the globe.

Final Notes

Thus, as the Royal Aero Club turns 111 years old today in aviation history, it looks back on a long and proud heritage of aviation successes. Above all, none could have imagined all these years later that all of this would result from an accidental fire of a French-built automobile. One can only hope that the Royal Aero Club’s future will be as bright as its past.

Here is some supplemental information from the Royal Aero Club website:

http://raec.websds.net/hbalbum.htm

The Crystal Palace was not in the City of York but in the southeast suburbs of London. The area was previously known as Sydenham Hill and became known as Crystal Palace when The Crystal Palace was re-erected on the top of Sydenham Hill in 1854 (a smaller version had previously been erected in Hyde Park central London to house the Great Exhibition in 1851). It burnt down in 1936. For further information on The Crystal Palace have a look at this website: http://www.crystalpalacemuseum.org.uk

Nigel —

You are correct, there was an inadvertent double-meaning that has since been corrected in the online story. Thanks for your support and support; if you ever see anything that doesn’t match your recollection of history, please let us know. We work hard for accuracy and need your help to be sure we get it right.

Thomas.