Published on November 18, 2012

Night flying was a new experience for aviators 100 years ago, carrying untold risks and yet drawing the interest of many who heard tales of how the world seen by moonlight from above was magical, as if lit with thousands of points of light similar to stars spread across the ground. Yet many wondered too beyond the joy of flying in a world of darkness and light, how would one navigate? How would one land? How could one take off safely. The questions were many — and thus, Flight, the newsletter of the Royal Aero Club, carried a special report on the topic, which was landing in post boxes across England 100 years ago today in history. To gain the best insights, they interviewed Mr. Sydney Pickles, the chief instructor at the Ewen School at Hendon, since there were held several night flying exhibitions that had seen his Caudron dancing in the skies to the light of fireworks. What glorious display!

Taking Off from the Airfield

As Mr. Pickles noted:

“Is there any special difficulty? Broadly speaking, I should say no. The great difference between flying by day and flying by night is, that in the latter case on eas to fly almost entirely by instinct. Take, for instance, the get-off. You arrange your machine so that you get a clear run over the ground; your engine is started, and you speed forward, steering direct for, we will say, a light in the distance. Instinct soon tells you when you have reached your flying-speed, and you pull back your lever for ascent. The vibration due to the machine running over rough ground suddenly cases, and you are in the the air.”

This reminds us that in those days, they had no landing fields with runway lights, no blue taxiway lights to guide one to the runway, and no runway end identifier lights that would signal a pilot that they were about to reach the end of the strip. But what was the end of the strip? The trees? The ditch before the nearby road? Familiarity with the field was necessary and would point the plane toward that part of the airfield that gave you enough clear space ahead, without undue bumps or brush, to get off and aloft before something came ahead that might cause a wreck.

Climb Out and Cruise

Climbing out was similarly a matter of “instinct”, as related Mr. Pickles:

“As for climbing, perhaps some people might think that, being unable to gauge your rate of ascent, from noticing the ground or land marks around you, there would be a danger of trying to force the machine up too great an angle and so losing speed, with probably disastrous results. But here again instinct comes in. You can always judge from the beat of the motor and the feel of the control lever whether you are adopting the most advantageous angle for ascent. once you are up and well clear of the ground nothing much happens, and the only thing you have to be careful of is to so steer your course that should the engine stop you would be able to plane down and land on a clear piece of ground. Here I must say that it is essential to be thoroughly familiar with your machine and the ground over which you are flying.”

This descriptions brings us to recall too that in those days a century ago, the men pioneering the way lacked even the most basic of flight instruments, such as an airspeed indicator from which to judge their angle of climb, though altimeters were available to set besides the compass that some planes might mount. According to Mr. Pickles, one should fly just by sound alone and the “feel” of the aeroplane and thus keep the machine from stalling out and plunging to earth. In that regard, we should also remember that the envelope was narrow, with top speed not that much more than stall speed.

Unexpected Risks of Night Flying

Mr. Pickles then describes the risks that can catch the inexperienced pilot, which can be camouflaged by the sublime experience of being aloft at night — his words relate those concerns perfectly:

“Flying in darkness, the lights of the illuminated aerodrome below attract most of your attention as far as exterior objects are concerned, and, constantly looking down, there is a this tendency to allow your machine to lose altitude. Besides this, it is difficult at first, in darkness, to judge your height from the appearance of lights on the ground. You think you are at 500 ft. when you are only in reality 100 ft. from the ground. In this respect it is very much like the delusion you suffer when you are learning to fly, and you climb for the first time to about 100 ft. You come down thoroughly pleased with yourself, thinking you have surprised the boys by going up to about a thousand, that is if you have not beaten the world’s altitude record. There may be danger in this, and I certainly advise anyone who intends going up after dark to carry an altimeter and have it illuminated.”

The Landing — a True Challenge

After a brief passage cautioning about the dangers of putting lights on the aeroplane which might cause the pilot to lose their night vision from the glare, he goes on to describe the most dangerous feature of the entire night flying experience — that of landing:

“Landing is perhaps the operation over which the greatest amount of care has to be taken when flying at night time. I found the best method was to vol plane down until about 50 feet off the ground, and then gradually approach terra firma by switching on and off alternately. As soon as you catch a glimpse of the ground you must flatten out immediately, for whereas you think you are perhaps 20 feet, you are in reality only about six. Then you gradually lower the machine down till the wheels touch.”

In other words, they were landing blind — the equivalent of a modern plane landing on a dark grass field without the aid of a single instrument, a true 0-0 experience. It is a wonder that they survived — and yet Mr. Pickles ends by tossing off the danger as being nothing of concern:

“Is there much danger? Here again I would say no, providing that you do not attempt to fly in anything but practically a dead calm, that you keep wel within the confines of the aerodrome, and that you remain constantly on the alert, confident that, should your engine stop, you could land on clear ground.”

Piece of Cake

Looking back, we can imagine what it must have been like, in an era that was more than 20 years before the invention of instrument flying. Aviators took risks, but all too often, we fail to make note that it wasn’t just about pioneering ever more powerful aeroplanes and better flight control systems and aeronautical principles, it was just as much about learning the personal lessons of how to fly, what worked and what didn’t, at a time when so little was known — or appreciated — about the art and science of flying.

From across a century’s time, we owe these men a debt of gratitude for taking those first steps and showing us the way, and thus giving us the gift of their experience that makes flying today the safest means of transportation on Earth (or off of it!).

One More Bit of Aviation History

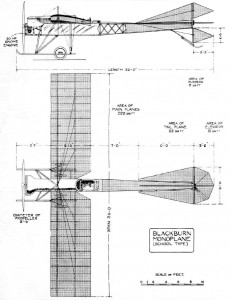

In the issue of Flight from 100 years ago, there was an interesting entry describing Mr. Moreau’s “Automatic Stability Monoplane”. The writer reported the following:

“The main idea of this system is that when the pendulum seat is hanging perpendicularly relative to the line of flight, the tail is in a position which makes for a horizontal flight path. Should the machine tend to climb, the pendulum seat changes its position relative to the rest of the machine and in doing so automatically re-adjusts the tail to restore the machine to normal level flight….”

The writer noted, however, that simple pendulum-based flight controls had their drawbacks:

“He found that, should the engine stop in midair, the pilot’s seat swung forward with its own inertia and set the tail for ascent — a very uncomfortable position to find oneself in with one’s engine stopped.”

Thus, it would seem that there was a long way to go before the first successful autopilot would be created — and to that, the world would await the developments of Mr. Sperry in America.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who was the first pilot to take off before sunset and land after dawn, following an overnight flight? And when did this take place?