Published on November 1, 2012

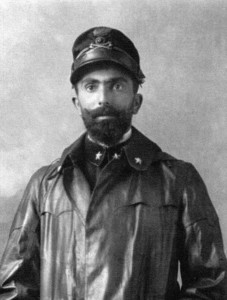

“Today I have decided to try to throw bombs from the aeroplane. It is the first time that we will try this and if I succeed, I will be really pleased to be the first person to do it,” wrote Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti to his father. With other military aviators of the new Italian Royal Army Air Services Specialist Battalion, Lt. Gavotti had been sent to the Ottoman Turk provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica to fight in the Italo-Turkish War. His aeroplane was a Blériot monoplane, one of only a handful in Italy’s possession.

“Today two boxes full of bombs arrived. We are expected to throw them from our planes. It is very strange that none of us have been told about this, and that we haven’t received any instruction from our superiors. So we are taking the bombs on board with the greatest precaution. It will be very interesting to try them on the Turks.”

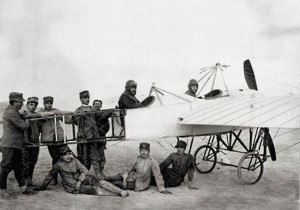

The Italian Army Air Force

The Italian Army deployed its entire force of aeroplanes to Tripolitania, arriving on October 15. This consisted of three Farman biplanes, two Nieuport IV G monoplanes, two Blériot XIs, and two Etrich Taubes — just nine aeroplanes overall. Eleven pilots plus 30 airman also disembarked. As well, at least two dirigibles were deployed to undertake bombing missions. On November 1, 1911, within days of his arrival in North Africa (Lt. Gavotti had helped load the planes to ship them by sea to the war front). Meanwhile, the Turkish forces had encamped at all of the strategic oasis sites in the three provinces, figuring that control of access to water was critical to controlling the vast expanses of desert.

The Italo-Turkish War began on September 29th and would last a full year until October 18, 1912, as Italy took advantage of the weakening Ottoman Turks and sought to expand its new empire. The Royal Italian Army would deploy a complete range of modern weaponry that was unique in the history of warfare. First, it was the use of aircraft, but it was also the first use of an armored vehicle, with the forces racing along desert roads in the Fiat Arsenale, an armored car and precursor to the first tanks of World War I. As well, Italy brought heavy artillery — facing them, the Turks had little more than lightly armed infantry and irregular Arab forces that were recruited locally.

At the time, Italy was a new country, having only joined together from a formerly independent set of city states into a single nation-state. Now, to compete in the colonial ambitions of Europe, the relatively new Kingdom of Italy was flexing its muscle. One of the first ventures was the little known conflict with the Ottoman Turks over provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica.

Lt. Gavotti’s Mission

Lt. Gavotti took off and headed out toward the oasis at Ain Zara, a sparsely treed oasis in the midst of the desert. Navigation was by taking a heading and scanning the horizon for the oasis. He flew at approximately 600 feet, well within range of rifle fire if the Turks recognized him as a threat. As it was, no aeroplanes except the Italians had yet flown over the region and they had been flying for only a week, since the first flight of a Blériot XI by Captain Carlo Piazza on October 23 and, on the same day, a flight by a Nieuport IV G undertaken by Captain Riccardo Moizo. Two days later, on October 25, Moizo returned with three bullet holes in the wings of his airplane — the first time an aircraft had been fired on in flight during war — the Turkish were taking action to counter the Italian aeroplanes.

“After a while, I notice the dark shape of the oasis. With one hand, I hold the steering wheel, with the other I take out one of the bombs and put it on my lap. I am ready. The oasis is about one kilometer away. I can see the Arab tents very well. I take the bomb with my right hand, pull off the security tag and throw the bomb out, avoiding the wing.”

As it happened, the 2,000 man strong Turkish camp never expected an air attack. Days earlier, another Italian aeroplane had flown overhead to do reconnaissance, which was widely viewed as the sole role of the flimsy light planes of that time, only 8 years after Wilbur and Orville Wright had first flown at Kitty Hawk and just a couple of years since the Wrights had shown the way with the 1908 at Le Mans with their European tour that revolutionized aviation across the Continent. The bombs were small balls, described as being the size of grapefruit and each weighing about four pounds. They were filled with a mix of potassium picrate that was developed specifically for the weapon by Lt. Giuseppe Cipelli at the San Bartelomeo di la Spezia torpedo factory in 1907 and 1908 (he was killed that year in the accidental explosion of the weapon).

To prepare and drop them, Lt. Gavotti first had to screw in the fuse while flying with one hand. Then, he would lift it to his teeth, biting onto the circular end of the pin, and pull it with his teeth. Then, as he made turns over the oasis, he threw the bomb down at the Turks below. Then, he would reach into the leather bag for the next bomb, all the while flying with his one hand on the stick.

“I can see it falling through the sky for couple of seconds and then it disappears. And after a little while, I can see a small dark cloud in the middle of the encampment. I have hit the target! I then send two other bombs with less success. I still have one left which I decide to launch later on an oasis close to Tripoli.”

Lt. Gavotti then returned via the oasis at Tagiura, where he dropped his fourth and last bomb. When Lt. Gavotti returned to the field at Tripoli, he was cheered by fellow aviators and saluted by his commanding officer, General Caneva. He wrote, “Everybody is satisfied”.

Final Thoughts

Lt. Gavotti’s mission was nothing less than a revolution. The Italian press ran stories of the great exploits of Lt. Gavotti, calling him “the flying artilleryman”. As the term bomber and bombing had yet to be coined, he was trumpeted as having innovated “the art of winged death.” It may not have been the first bombing mission, though many claim it was and certainly, it was the first by a European pilot.

What would follow was a long history of aerial bombing warfare, with a constantly evolving and ever more deadly set of tactics and countermeasures. Nobody will ever know if Lt. Gavotti’s four hand bombs did any damage or killed anyone, but the legacy of his action is one of the most deadly in the history of aerial warfare. Of interest, six months later, on March, 1912, Lt. Gavotti would also fly the first military night mission.

One More Bit of Aviation History

The Italo-Turkish War would culminate with the unification of the three North African Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan and Cyrenaica into the new nation of Libya. During the war, the Italian airmen would innovate a series of military missions for aircraft that none had ever tried — in fact, Italy set the new standard for the use of aeroplanes during war. For instance, October 28 saw Captain Carlo Piazza directing fire from the Italian Navy battleship Sardinia against the oasis at Zanzur. On November 24, Captain Moizo in his Nieuport IV G directed land-based artillery in counter-battery fire. Then December 4 had the aircraft escorting three Italian infantry and armored columns across the desert, scouting ahead for potential ambushes.

The innovations continued into 1912 when on February 23 a Bebè Zeiss camera was mounted on a Blériot and flown by Capt. Piazza — as he couldn’t fly and change the glass plates in the camera, he took only one photo. This was the first photo recon mission in history. Finally, when some of the aircraft (the Benghazi “squadron”) deployed to Sabri, they found themselves caught by mud — the solution was to build the first artificial runway in aviation history, a 100 meter strip that was 12 meters wide, made of wooden planks.

During the 100th anniversary year of the Italo-Turkish War, Europe would once again deploy air power to Libya in support of the rebel overthrow of the rogue government of Muammar Qaddafi. Once again, Italian air power (F-16s and Panavia Tornado aircraft) would be seen in the skies near Ain Zara and Tripoli — it seems that history is destined to repeat itself.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What was the name and story of the first American aviator to drop a bomb during a conflict?