Published on November 14, 2012

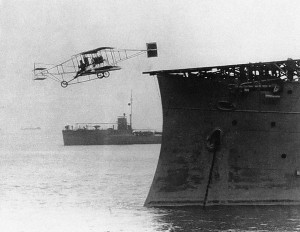

On November 14, 1910, the light cruiser USS Birmingham was at anchor in the harbor at Hampton Roads, Virginia. On its foredeck, a makeshift wooden platform had been constructed and a Curtiss Pusher aeroplane had been hoisted aboard for the tests. The plane’s pilot, Eugene Ely, ran up his engine to full power as a small group of sailors held onto the wings. With a signal from Ely, the men let go and the Curtiss Pusher raced across the short wooden platform into the air. To help accelerate, the ramp was angled at a slight down angle. Based on the height of the platform above the water, Ely hoped that once clear of the deck he could dive down and pick up enough speed to pull out before hitting the water. Yet as the plane plunged downward, Ely realized that there was no way he could avoid hitting the water. In those precious seconds before impact, he pulled back on the stick carefully, but then the wheels struck the water….

First Foray into Naval Aviation

A month earlier, Eugene Ely had met with US Navy Captain Washington Chambers, who had been assigned by the Secretary of the Navy, George von Lengerke Meyer, to evaluate possible naval uses of aircraft. Ely, though a civilian, was a willing participant in the trials that Capt. Chambers was considering and so, with a small contract, he was hired for the feat. For Eugene Ely, such daring deeds were not atypical. He had grown up in Iowa and, having taken a job as a chauffeur for a Catholic priest, had taken to secretly racing the church car in his off hours. Later, after having moved to Portland, Oregon, where he took a job selling cars for E. Henry Wemme.

Ely’s life took a turn into aviation when Wemme signed a sales deal with Glenn Curtiss to represent and sell aeroplanes in the Pacific Northwest. Wemme took delivery of a Curtiss Pusher to use in demonstration flights. Recognizing the risky nature of aeroplanes, Wemme did not wish to try to fly the aeroplane, but Ely considered it to be a natural extension of his amateur speed runs in automobiles. Climbing into the new Curtiss aeroplane, he got it started. Predictably, since he had scant instruction, he wracked it up on the first flight, escaping unharmed. Feeling bad about the situation, Ely purchased the wreck from Wemme. In the weeks that followed, on his own, Ely rebuilt the plane and returned it to flyable condition. Ely’s second flights went better and he was soon flying short hops with confidence around the Portland area. Then he traveled to Minnesota to fly more demonstration flights. That trip lead to a job flying exhibition flights for Glenn Curtiss and shortly afterward, Ely earned Aero Club of America certificate #17, which he passed on October 5, 1910.

The Flight into Naval History

Within days, he was introduced to Capt. Chambers and the Naval exhibition flight was arranged to test the feasibility of launching an aeroplane from a ship. On Chambers’ direction, over the following few weeks, the wooden launch platform was built on the foredeck of the USS Birmingham. Everything was readied and the plane was lifted onto the deck with the help of a floating crane. With little fanfare, Ely had launched from the platform and instantly, the Curtiss Pusher angled downward toward the water, gathering speed toward what looked to be an inevitable crash. Pulling back on the stick, it seemed that the Curtiss Pusher couldn’t avoid hitting the water. Carefully, Ely flattened the descent — but it was no use.

He pitched upward, being careful to avoid a stall as the wheel struck the water with a massive splash. Salt water spray showered Ely and covered his clothes and goggles. As well, the plane’s underside was doused, yet somehow the Curtiss Pusher didn’t flip forward into the waves. Instead, it bounced off the water’s surface and rose a bit off the waves. Holding it barely above a stall, he held the plane inches above the low waves as the speed built up — only years later would aeronautical engineers work out how ground effect works to allow a plane to fly a lower speeds than possible when against the surface. It was this that aerodynamic quirk that saved Ely from a watery crash.

As his speed picked up, Ely gradually climbed to a safer altitude. The original plan had been for him to circle the harbor at Hampton Roads before landing at the Norfolk Navy Yard nearby, yet Ely was worried about the water damage to the plane. Without hesitation or second thought, he turned straight toward the nearest shore. As soon as he crossed the surf line, he turned and landed on the sand. It was a good landing and he got out to check the plane. There was no damage. Ely was doused with sea water, his goggles covered with water droplets, but he was exhilarated — he had pulled off the first successful launch from the deck of a US Navy ship. The test was a success, even if he had missed the official welcoming party at the Navy Yard.

Aftermath

Eugene Ely’s successful first launch off the deck of a ship heralded the beginning of US Naval aviation. Two months later, Ely agreed to continue with additional tests at the request of Capt. Chambers. Thus, on January 18, 1911, he achieved the first successful landing on a Naval ship with a fixed wing, heavier than air plane — his Curtiss Pusher — when he touched down on a platform built atop the heavy armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania while it was anchored at San Francisco Bay, California. In that event, he tried out a new method for stopping the aeroplane — a tail hook. As it happened, Ely successfully caught a wire and stopped on landing. Afterward, he was heard to say that the act of landing on a ship was easy. As he noted, “It was easy enough. I think the trick could be successfully turned nine times out of ten.”

Today’s Naval aviators might disagree a bit with Ely’s assessment of the ease of landing on an aircraft carrier. But then again, Naval aviators these days are not landing at 20 mph onto the deck of a ship anchored in a harbor on a windless day with no waves….

One More Bit of Aviation History

The first tail hook for the US Navy was not designed by a professional engineer or Naval officer, but rather by an unexpected player — an inventor and aerial showman named Hugh Robinson who was fond of exhibition flying and had pioneered a number of aviation firsts. Using his talents and experiences while working with both Capt. Chambers and Eugene Ely, he developed a tail hook apparatus that would be strong enough to stop an airplane in motion safely, for both the airplane and the pilot. Virtually every Naval tail hook and arresting system since is in some way based on Robinson’s design.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who accomplished the first aerial rescue of a downed aviator in the water offshore?