Published on December 19, 2012

By Thomas Van Hare

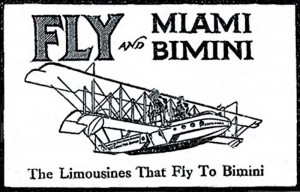

In 1917, Arthur “Pappy” Chalk began a small charter airline called the Red Arrow Flying Service in Florida. Shortly afterwards when the US entered World War I, he suspended the airline’s operations and joined the US Army to fly. After returning from the war, in February 1919 he restarted his airline, renaming it, Chalk’s Flying Service. The first tickets were sold on the beach by Pappy Chalk himself from a chair in the sand under a simple beach umbrella. From these humble beginnings, a truly unique airline emerged, one that offered the glamor of yesteryear with flying boat service that plied the islands of the Caribbean. Despite its small size, over time Chalk’s became a living legend in airline history.

Over the ninety years that followed, Pappy Chalk’s airline only suspended service for three years during World War II, by order of the Federal Government, as well as for two days during Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and for a short while after 9/11, when all airlines in the USA were grounded. The world’s oldest airline finally ceased operations in 2007 only after a string of bad luck. Problems with its aging fleet of seaplanes, maintenance issues, and slackened demand for its primary island destinations of the Bahamas, created financial pressure for the airline. Over the years, the airline had survived through many ups and downs and had carved out a name for itself in aviation history.

The Challenges of Seaplane Operations

For many years, Chalk’s operated from Watson Island, a small island in the heart of Miami’s Biscayne Bay. The airline’s fleet were almost entirely seaplanes. Prior to WWII, few runways were available for airline use. As a result, many airlines operated seaplanes (flying boats) to serve routes of cities along the oceans and waterways of the world.

For Chalk’s too, this was a wise choice. Seaplanes enabled access to the islands of the Caribbean without the need for runways. The planes could take off and land on the water, then taxi up to the beach to disembark passengers. However, thousands of runways were built during WWII, revolutionizing the global aviation industry. When the other airlines shifted to land-planes, Chalk’s elected to remain a seaplane-only operation. In a sense, it had little choice since its primary destinations the Bahamas were still only accessible from the water and beach.

There was romance to it as well, however, and the unforgettable passenger experience of taking off from the water in a seaplane and traveling out to the islands became the calling card for the airline over the years. Seaplane service was convenient too. By the 1990s, Chalk’s would fly not to the airports of Nassau, from which passengers had to take buses or taxis to the larger hotels, but rather the airline was landing on the waters just offshore where the main hotels were located. The passengers would disembark on the beach and walk into hotel itself, assisted by porters who would carry their luggage.

Demand for seaplane flights to and from the islands had always been a small niche market, yet this also meant that Chalk’s, despite its small size, never suffered from undue competition — thus, the very reason the airline could never expand was also not only its raison d’etre, but the only reason it survived for so many decades.

While Pan American expanded from Miami and extended northward up the US east coast and down south to Cuba and beyond to Latin America, Chalk’s remained a small airline. It was never a threat to the large dreams of the big “airline barons”. It never enjoyed the extensive financing that the likes of Juan Trippe could command.

Chalk’s suffered from high costs nonetheless. Seaplanes were always more maintenance intensive than land-based planes. The wear and tear from landing on the rough waves and the salt water damage were significant risks. Fighting corrosion was a constant battle for the airline’s maintenance staff.

Supplementing Income

Chalk’s found itself year after year operating with small profit margins. Even from early on, it had to find creative ways to supplement its income. During the years of Prohibition, Chalk’s was the premiere smuggling operation for illegal alcohol imports, flying booze from the Bahamas to Miami. Even if the authorities found out about it, it seemed that Chalk’s was able to continue flying. It earned considerable profits from alcohol flights, even if under the table.

By 1966, Pappy Chalks sold the airline, though he stayed on in management until 1975 before finally retiring. After that, his vision and guiding hand were sorely missed. The airline went through a series of new owners, each with their own parochial purposes in mind. At one point, resorts bought in and sought to dedicate the airline to flying only their own vacation customers. As a result, the airline’s popularity alternately improved and waned. In 1982, for instance, the airline flew a record 50,000 passengers. Even so, the good times didn’t last. A bankruptcy followed and a series of new owners changed the airline repeatedly. Still, Chalk’s was able to modernize and upgrade its fleet of seaplanes. Ultimately, the airline owned and operated around a dozen Grumman Mallard seaplanes that had been modified so that they were powered by reliable and fuel-efficient PT6 jet turboprop engines.

Disaster and Crisis

In the end, the seaplanes that created the demand for tickets also proved to be the greatest challenge for Chalk’s. As the airline neared 90 years of age, the ever more challenging and non-competitive cost structures associated with seaplane operations dragged it into the red.

When virtually all other airlines had made the transition to land-planes in the late 1940s, aircraft manufacturing had naturally followed suit. The US seaplane production had stagnated and all but died. Put simply, there were simply not enough airline customers to support that segment of commercial aviation design. Chalk’s was left operating a fleet of aging seaplanes, even if their engines had been upgraded for improved fuel efficiency and maintenance. Metal fatigue was an increasing concern.

With the continuous wear and tear of such operations, the airline had its first serious accident in 1994. One of its seaplanes sprung a hull leak and sank at Key West, killing the captain and copilot. There were no passengers on board at the time, thankfully. Nonetheless, the accident highlighted the difficult maintenance challenges that airline faced.

Then on December 19, 2005 — today in aviation history — the airline suffered its worst accident. The accident spelled the end for the world’s oldest, continuously operating airline. One of the airline’s Grumman Mallards suffered a catastrophic inflight failure from the metal fatigue of countless water landings over the year. The wing separated from the plane during a routine flight from Ft. Lauderdale to Bimini after an unscheduled stop at Watson Island. Shortly after take off from Bimini, the aircraft crashed into Biscayne Bay. All 18 passengers and both pilots were killed.

Over the following two years, the airline worked with the FAA to correct the metal fatigue and maintenance issues it faced. For eleven months, it ceased operations. Finally, it was able to restart operations in late 2006. However, with the final publication of the NTSB recommendations and final FAA reports pertaining to the causes of the 2005 accident, despite having complied with the FAA’s demands regarding metal fatigue, the FAA revoked the airline’s operating certificate in 2007. Shortly afterward, the airline went into bankruptcy and liquidation.

Final Thoughts

Today, we can look back and remember Chalk’s as an airline that preserved the romance of passenger seaplane travel long after the rest of the industry had experienced the jet age revolution. Deregulation, cutthroat competition from low cost carriers, and a host of other major transitions were the major stories of airline history, yet Chalk’s flew above it all somehow. The little seaplane airline somehow weathered the turbulence and flew on as the last of the old style seaplane airlines. In the end, flying on a Chalk’s seaplane was a bit like flying on the Concorde. It was one of those things that was a “must do” flight for aviation enthusiasts worldwide. It was a way to enjoy history and flying at the same time — and to recall the “good old days”.

With the end of Chalk’s, we can only look back upon the time when passengers flew from the seaplane docks of Miami to the Caribbean island’s most posh resorts. We can imagine what it must have been like to take off and land on the water and then to pull up to the beachfront hotel. We can dream of disembarking onto the sand to the welcome of a tropical rum drink offered by a smiling resort staff as the porters carried the luggage into the hotel lobby.

Chalk’s seems the stuff of Hollywood films and nostalgia, recalling a pleasant, personal touch and a bygone era. Sadly, memories are all there will ever be. An airline like Chalk’s will probably never happen again.

One More Bit of Aviation History

To dramatize the difficulties of operating a seaplane airline, one need only look at the specifications and flying hours on the Grumman Mallard that crashed in 2005. The aircraft was certified back in 1944. The design was 61 years old at the time of the crash. The Mallard was an aging design with many flaws; it reflected the design knowledge of the 1940s. The stresses on the plane, which was itself manufactured in 1947, were overwhelming. The metal fatigue problems that afflicted most of the fleet were largely undetectable in normal maintenance. Stress cracks were hard to spot. Wing rib damage was obscured by built up layers of sealant that covered inside wing structure. The plane that crashed had a total of 31,226 flight hours. It had flown 39,743 cycles (the airline term for each take-off, flight and landing). Just how long could such a seaplane fly before something happened? In retrospect, it wasn’t a matter of if it would suffer a catastrophic failure from metal fatigue, but rather when.

Finally, while Chalk’s would have loved to upgrade its fleet to newer passenger certified seaplanes, in fact, it couldn’t. There were no approved passenger certified, commercial seaplanes being manufactured — anywhere in the world. In other words, the airline had no future, no matter what it did. At some point, its Grumman Mallards would have been all retired anyway. For Chalk’s, there was no way to continue its operations with land-planes either. That market that was already dominated by the major airlines and the low cost discount carriers. Without the unique niche and nostalgia that the seaplanes brought, the airline was doomed.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What other great seaplane airlines have existed in history? Note that there are several good answers as the field had numerous excellent competitors for many, many years.

I can remember seeing an Imperial Airways 4 engined Flying Boat called “Caledonia” in the late 1930’s. It was making a tour around the British Isles to show the flag to the people. It landed on the Humber River at Kingston upon Hull. I saw it when it took off to the west and turned away. It was the most magnificent sight of an “aeroplane” I had ever seen and it has stayed with me all those years since.

Imperial Airways had quite a few of them and flew all over the place. It changed it’s name to British Overseas Airways Corporation, (BOAC) a few years later.

Two seaplane airlines come to mind. Dick Probert’s Avalon Air Transport which flew the route to Catalina Island off the California coast and Charlie Blair’s Antilles Air Boats operating in the Caribbean. Both, at one time of the other, utilized the Excambrian, the only survivor of the three VS-44A flying boats built by Sikorsky. The Excambrian is now on display at the New England Air Museum, Bradley Field, just north of Hartford, Connecticut.

Although none of the following flew strictly flying boats, Pan American, Imperial Airways, and Aeropostale pioneered trans-oceanic air commerce in flying boats.

I was a frequent flier with Chalk’s before and after the re turbo power. On a flight from Cat Cay when they flew there, after landing to pick up three passengers bound for Miami, the pilot informed us of dead batteries. He organized a golf cart and 200′ rope where I was summoned as a helper to pull the line, assisted by the golf cart. The pilot gave us the thumbs up from the cockpit, the line was carefully wound around the prop hub, and we all pulled. That is how we started the plane’s one engine. Once running, the other fired off the electrical current produced by the first. He said he did it frequently.

— Capt Bob Kimball, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida

My very first job in 1970. I worked part time there. Capt, Ned (can’t remember his last name) took me to Bimini one Saturday. He asked if I was real busy and I said no and he said put your name as co-pilot on the manifest and let’s go. Quite an experience. I was so sad when they had that crash.

These are all wonderful answers! Thank you! It is worth adding that Pan Am itself was a seaplane airline before WWII, as were the airlines that become British Airways!