Published on December 21, 2012

“During the last year or so great strides have been made in Germany in the development of the aeroplane, although the progress has been by no means easy, owing to the way in which the dirigible has captivated the mind of the public. While the aeroplane was developing from the ‘fledgling’ stage in France, the success of the three different types of dirigible, Zeppelin, Gross and Parseval, was keeping Germany so occupied that there was pracitcally no room for consideration of heavier-than-air machines. Still, in spite of the lack of encouragement, both practical and moral, a few experimenters bravely struggle on….”

So wrote the writers at Flight precisely 100 years ago as the British Royal Aero Club reviewed the progress of aeroplanes and aviation in general in the country of Germany, a nation that many regarded as a potential combatant in a future war in which, they all knew, aeroplanes would play a part. As 1912 came to a close, the British could not have foreseen just how right they were, as a major war was but but 18 months away.

Reviewing the Latest German Machines (1912)

Wilbur Wright had flown the first time in Germany at Templehof, aside Berlin, which took place on August 8, 1908. In the next few years that followed, many others came from France and England to show their aeroplanes and aviation began to truly “take off” in Germany. Though Zeppelins continued to dominate the news, it was the aeroplane that would show the most promise worldwide and German companies were soon producing French and American designs under license. Experimenters were soon producing some outstanding and innovative designs, considering the technologies of the day.

“Generally speaking, it may be said that while the French designers have been striving mainly for speed the Germans have paid a great deal more attention to the question of lateral stability…. In monoplane design the influence of Grade and also of Etrich has been very marked, many machines having the under slung position of the pilot of the former, while the bird-shaped plane, evolved by the latter in a modified form, is quite common…. With regard to biplanes, the Albatross Co. exhibited at the 1911 Paris Salon one of their machines in which the tips of the upper plane were arranged somewhat on the Etrich plan. Since then, however, this firm have abandoned this system in favour of main planes with a flattened V form similar to the ‘Lohner’ arrow ‘plane,’ entered for the British military trials. The Mars biplane is on more or less the same general lines.”

The aspects of speed design that seemed to interest the British and French were surpassed by the German’s desire to produce planes that would be more comfortable to pilot and fly — as the reviewers noted in a seemingly envious tone that also made reference to Germany’s dominance in automotive design:

“As speed has not been deemed so important, German designers have given a good deal of attention to the comfort of the pilot and passengers, and their machines are generally very substantial both in size and construction. Being past masters in the art of metal work, they have displayed great ingenuity in casing in the motors, &c., while automobile practice has been largely followed.”

Finally, the writers made note of a few advances, some of which, like the aileron design of the Mars, would soon spread worldwide and be widely adopted by aircraft designers.

“In the Mars biplane ailerons are only fitted to the upper planes. The fuselage and landing chassis of this machine is exactly the same as on the monoplane turned out by the same manufacturers, and, except for the wings of course, the various parts of the machines are interchangeable…. The Jeannin follows very much on Hanriot lines…. A machine which has achieved success, not only in its own country, but elsewhere, is the Harlan, a number of which were supplied recently to the Turkish Army.”

Overall, the British view of developments in German aviation was seen through the British lens. In most cases, the view was that British designs were superior among sportsmen, though the British Government had yet to catch on to all of the advances. Nonetheless, it was the Zeppelin, above all, which was a cause for concern, since no other nation had advanced their dirigible designs to the extent that Germany had. That such machines would take to the skies and bomb British cities during the upcoming four years of war was expected — the writers only hoped that German Zeppelins could be intercepted by the new British aeroplanes that were under development at the time.

One More Bit of Aviation History

The final issue of Flight for the 1912 year included a salute for the coming year and a look back but also yet one more report of France’s rising star in aviation, Roland Garros:

Garros Flying from Tunis to Paris.

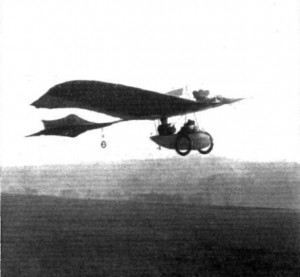

Having achieved his object of regaining the height record, Garros conceived the idea of making the journey back from Tunis to Paris on his aeroplane. After having had everything in readiness for three days, he was able to make a start on the morning of December 18th. Setting out from Tunis he flew round the Bay of Tunis to Cape Bon and then struck across the Mediterranean for Marsala in Sicily, where he effected a safe landing, the distance covered being something over 150 miles. After a rest, Garros restarted and flew along the coast of Sicily to Trapana, where in landing he slightly damaged his petrol tank. On Saturday Garros made another start, flew across to the mainland of Italy, and reached Naples. He arrived at Rome on Sunday afternoon. From there the course will be more or less familiar to him, as it will be remembered that he was second to ‘Beaumont’ in the Paris to Rome race. He is using a Morane-Saulnier biplane, itted with a 50-h.p. Gnome engine and Chauviere Integral propeller.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What happened to Prof. Reissner, one of Germany’s more innovative designers and why didn’t his designs become more popular?