Published on December 17, 2012

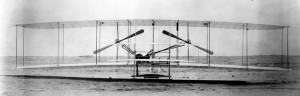

On this date in aviation history, 109 years ago, the Wright Brothers made their first successful flights of the Wright Flyer I at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. In doing so, they achieved a truly extraordinary feat, becoming the first to fly a heavier-than-air powered airplane under full control. On their first flight, they achieved a distance of 120 feet. Three more times they flew that day, with the final flight extending to 852 feet in distance from the point of take off. Yet what it took to get there was more than pioneering a flight control system (they did that), perfecting a biplane canard configuration aircraft (they did that), or even teaching themselves to fly (they did that too). Beyond the host of other achievements, there were also two other truly great achievements that came together that day and made it possible.

Finally, there was one other “first” that happened that first day, on December 17, 1903, when the Wright Brothers flew at Kitty Hawk.

The Other Achievements

What had stymied many previous flight attempts came down to a simple challenge — how to produce enough thrust to produce sufficient speed that the wings could provide sufficient lift to overcome the drag and weight of the aircraft and thus fly. In other words, they needed a powerful engine and an excellent propeller design that could efficiently capture the horsepower of the engine and convert it into propeller thrust. Therein were the two key problems — engines of that era were far too heavy compared to their horsepower and making efficient propellers was a uncertain engineering challenge.

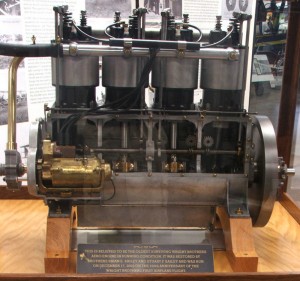

To solve the engine problem, since a heavy airplane would be more difficult to lift off the ground, the Wrights combed the marketplace looking for solutions. They found none. Everything available was too heavy and did not offer sufficient power. Their only option was to develop their own engine from scratch. While they had spent several years pioneering the aerodynamic principles of flight and the flight systems needed for full three-axis control, their aircraft engine was a late and very new development for the Wright Flyer I. As bicycle mechanics, however, they had the necessary skills to fabricate a lightweight design on their own. Studying the principles of engine mechanics, they literally redesigned engine ideas and casings on their own so as to get the weight down low enough.

Translating the engine’s horsepower to thrust, however, was a more interesting challenge. At first, the Wright Brothers thought that they could apply the principles and designs of marine propellers (ship props) to their aircraft. As such, they researched the field for the scientific formulas governing propeller dynamics. They were surprised that there were not any that they could find for maritime ship construction, much less a set of formulas for the design of efficient aviation propellers. Pondering the matter further, they realized that in fact each blade of a propeller was actually a wing with an airfoil, rotating about an axis — thus, the prop didn’t need to be treated as a new challenge with new ideas and new science after all. Instead, this theoretical breakthrough meant that they could apply their existing wind tunnel methods and tests (they had developed their own wind tunnels as well!) to the design of a propeller.

The Solution that Enabled Flight

The Wrights realized that a truly efficient propeller design had to be developed for the Wright Flyer I to make it off the ground. Mathematically, they were able to determine that they need a very high efficiency ratio to capture the limited horsepower output and torque of the engine and convert the bulk of it into thrust. Yet to convert the math to reality proved to be no small feat.

They pioneered a pair of eight foot diameter propellers rather than a single prop so that they could “bite” into more clean air with larger “wings” (or blades) on the propellers. To fly, they would need two propellers, rather than one. The engine was thus attached to a pair of identical (if mirrored) propellers by a bicycle chain and gear system. To eliminate asymmetrical torque, the props were counter-rotating. Further, they were mounted behind the wing so as to ensure that the airflow over the leading edges remained undisturbed, thus enabling the biplane wings to produce the lift that had been carefully designed into the airfoil.

Finally, they shaved a propeller from layered wood with twisted blades that enabled the thrust to be smoothly produced in the same relative amounts from hub to tip. At the tip of the blade, a faster traveling point on the blade vs. the propeller hub, the speed of the propeller was highest relative to the airflow, dictating a shallower pitch. Ultimately, the Wrights calculated that they had developed a propeller with 66 percent efficiency. With that, they reasoned, they could fly.

Later Tests

In fact, the Wrights were wrong. Their propeller calculations were somehow flawed. The propeller they had so carefully engineered did not produce 66 percent efficiency — incredibly, it was even better than that. Modern tests demonstrate efficiency ratings averaging at about 75 percent. Peak efficiencies are actually 82 percent. The Wright Flyer I at Kitty Hawk actually had more thrust than the Wrights had calculated was needed to fly. It was a good thing because as it turned out, the plane only flew at the very edge of the envelope. It was so unstable and under powered that most researchers agree that only the Wrights with their years of experience flying gliders of similar designs could have controlled it and kept it aloft.

In the end, it was these two design innovations that allowed the Wrights to fly, more than anything else. While history honors them for their invention of the heavier-than-air powered airplane, it should really perhaps honor them equally for their mechanical engineering talents at producing a lightweight engine as well as for their breakthrough aerodynamic work in developing propeller theory and a super efficient, brilliantly manufactured pair of mirrored propellers.

In the end, the Wrights were the only ones who truly brought everything to the table, from engineering to concepts, to skills in manufacturing, they were, if anything, the most uncommon bicycle shop mechanics in history.

The Last “First” of the First Day

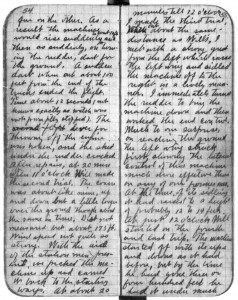

As a final note, history often neglects to pay homage to the very last “first” that the Wright Brothers achieved on December 17, 1903. After the fourth and final flight of the day, the Wrights and those few Coast Guard helpers who came to the small sand dune at Kitty Hawk to make the first flight were walking the Flyer back to its small hangar and workshop when a gust of wind kicked up. The Wrights knew that there was no way to hold onto the airplane in the wind. They let it go. One Coast Guardsman, John T. Daniels, however, tried to hold it down. The forces of aerodynamics and lift simply tossed him and the plane up in the air, flipped them and cartwheeling the plane over. The impact collapsed the Flyer into a broken heap. The Coast Guardsman suffered a broken collar bone.

And thus, the Wright Brothers marked the other, more ominous first of that date — the first casualty of the new era of powered flight. Sadly, it would not be the last — in the years that followed, as many pioneers pressed the limits of engineering against the walls of science, many, many aviators lost their lives, suffered injuries and lost their fortunes.

Airplanes are harsh mistresses, after all.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Modern propeller design has come a long way since the Wrights’ time. New propeller blade designs include everything from supersonic blade tip designs, stealth props and rotors, noise suppressing blades, and increases in efficiency that are the direct result of decades of experience and high powered computer-aided design tools, computational fluid dynamics and computerized milling for maximum performance. So just how good are today’s propellers compared to the Wright Brothers and their first propellers? Today’s finest light aircraft propellers peak out at around 85 percent efficiency — and only that when they are brand new, just “out of the box” and completely free of nicks and wear. In other words, the best we do today is only 3 percent more efficient than the Wright Brothers’ very first design — and that puts it all into perspective. The Wright Brothers were, in the end it seems, the most amazing slide rule aeronautical engineers and home-builders of the 20th Century.

Today’s Aviation History Question

How much did the Wright Flyer I cost in US Dollars at the time? What would be the equivalent value based on inflation since then of the “corrected, modernized” cost figure?

My great-grandfather, William Thomas Beacham, was a part of this. Several members of my extended family had a hand in helping the Wrights get their plane off the ground, both from the help my great-grandfather gave them to the people who owned the stretch of land on which they launched their plane. We also owned the land that later became the Wright Brothers Memorial. It is something all of us Beachams are very proud of.