Published on January 19, 2013

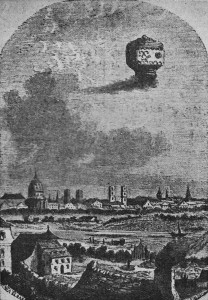

On the 19th of January 1784, at Lyon, France, the largest Montgolfier balloon ever constructed was readied for flight. Called “Le Flesselle”, it was 120 feet high and had a capacity of 700,000 cubic feet, making it not only huge for its day but one of the largest hot air balloons ever flown, even to this day. Sponsored by the governor of Lyon, Jacques de Flesselles, seigneur de Champgueffier en Brie et de La Chapelle-Iger, it would be crewed by two experienced balloonists — Joseph-Michel Montgolfier and Jean-Francois Pilatre de Roziers. Five noble and gentlemen passengers rode along, as reported in “Editions de LE NOIR”, including M. le Prince Charles Deligne, M. le Comte de la porte d’Anglefort, M. le Comte de Laurencin, M. le Comte de Dampierre et M. Fontaine de Lyon.

Disaster would befall the great balloon just 13 minutes into the flight as the balloon reached 3,000 feet of altitude. Its envelope ripped and it fell, impacting in a meadow near Lyon. Somehow, none were injured. All of the inhabitants of Lyon as well as 3,000 others had come to witness the feat. Despite the tragedy and death miraculously averted, the event was celebrated — truly, France had gone “balloon mad!”

Le Flesselle and the Balloon-Crazy Public

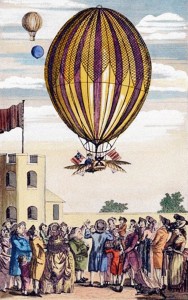

The first hot air balloon flight of the Montgolfier brothers, Joseph-Michel and Jacques Etienne, took place from the town square of the small town of Annonay, France, on June 4, 1783. It had been just a year since the Joseph-Michel first experimented with small, paper hot air balloons. After Annonay, the population of France — and very quickly, the entire world — became enamored with balloons and flight.

It didn’t take long for others to duplicate the Montgolfiers’ feat. Jean-Francois Pilatre de Roziers flew next in Paris, amazing the public. Soon balloon exhibitions were commonplace and tickets were sold to the public for access to the launch area, thus funding the projects. Commercialism extended from the balloons and pilots to a whole range of balloon-inspired goods and practices, ranging from small skin balloons that measured half a foot across (more or less), to furniture bearing carvings of balloons, wall papers, draperies, art, dinner ware, tea sets (balloons and tea anyone?) and even hairstyles and fashion!

On first look, while it was extraordinary that man had flown — an entirely unexpected achievement in an era of transformation that included the democratic revolution in America — the mania associated with balloons went far beyond anything imaginable. Flight was amazing, to be sure, but it represented something else — an example that mankind had entered a new era, where all things were possible. If man could fly, then certainly the future would be amazing to behold. What’s more, they were right, those born in the mid-1700s could have never foreseen the changes that would take place in their lifetime, just as today we are amazed by the digital revolution.

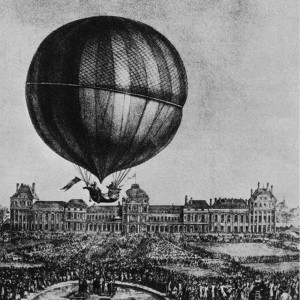

In 1783, when Jacques Alexandre Charles and Marie-Noel Robert made the first hydrogen balloon flight, fully half of the population of Paris gathered around the Tuileries to watch the ascent — in other words, 400,000 people had cheered and waved as the balloon rose upward. As Tom Crouch reported in a Smithsonian article that he had researched, one person recorded the moment of flight as this: “”It is impossible to describe that moment: the women in tears, the common people raising their hands to the sky in deep silence; the passengers leaning out of the gallery, waving and crying out in joy… the feeling of fright gives way to wonder.”

The Crash of Le Flesselle

On the cold January day, today in history in 1783, when Montgolfier and de Roziers ascended in Le Flesselle, they were but 13 minutes into the flight when the balloon’s envelope tore open high above. The rip took place at a spot where previous repairs had been made — apparently incorrectly. Immediately, the balloon began leaking the hot air that was essential for flight. For a moment the balloon hung in the sky and then seemingly it hesitated before it began to fall, slowly at first. As the winter cold dug into the envelope, it further hastened the cooling of the air within, “Le Flesselle” was doomed. Despite releasing ballast, the rate of descent only accelerated. A crash was inevitable — Montgolfier and de Roziers as well as the passengers could do nothing but hang on.

Finally, the balloon struck the ground. Somehow, the seven aboard survived the impact, though it was a jarring affair. As for “Le Flesselle”, it was never flown again. For the makers and for the public, the flight “Le Flesselle” heralded the view that the maximum size of balloons may well have been reached. In any case, the Montgolfiers never again attempted a balloon of that size. “Le Flesselle” was unique — and remains a grand gesture in a time of greatest, when man first conquered flight.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What type and size of balloon was the first to be shipped from France to England?