Published on January 5, 2013

Since the summer of 1914, when the Great War broke out in Europe, aviation advanced quickly. As the war progressed into 1915, the new Fokker Eindecker gave the Germans the upper hand in the skies. The German pilots were downing dozens of French and British reconnaissance aeroplanes and early bombers. Equipped with a plane that rightfully was the world’s first true fighter plane and it brought about an era known widely as the “Fokker Scourge”. The answer to the “Scourge”, however, would come in an unlikely form, a plane so small it was called the Bébé.

Ending the Fokker Scourge was one of England’s and France’s paramount goals in the air war of late 1915 and 1916. The problem wasn’t the quality of the pilots or their training, however, it was that new and better aeroplanes were needed. The French Nieuport company, a prewar manufacturer, had just the right answer. They took their proven training plane, the ungainly Nieuport 10 — a plane that had already been drafted into a fighter role — and improved it by making it smaller, lighter and more aerodynamically pure. Additionally, the company mounted a Lewis machine gun on the top of its wing, thus enabling a forward firing weapon, allowing the pilot to point the plane at the enemy, thereby aiming the gun.

The result was the Nieuport 11, known among pilots as the Bébé (Baby), a tip of the hat to its diminutive size. Yet this small package would have a huge effect. The Nieuport Bébé, introduced on January 5, 1916 — today in aviation history — would prove to be the key to bringing an end to the Fokker Scourge.

The Battle of Verdun

The Great War of 1914-1918 was a massive undertaking, pitting infantry and cavalry against one another, supported by massed heavy artillery. In comparison, the air war was a minor sideshow. Generals commanded men — not thousands, but hundreds of thousands of infantry troops. Materiel and logistics fed the front line, which became a muddy, meat-grinder of death. Men were sent into battles where they were murdered at rates that would astound modern citizens.

When the Battle of Verdun was joined, the Germans had but one key strategy — to use their massed heavy artillery to kill so many French soldiers that eventually their army would collapse, thus opening the door to victory for Berlin. It was a question of managing the death rates on both sides so that the French army would fall before the German one.

This meant that Germany would lay siege to the French fortifications at Verdun. Their idea was that the French would continuously reinforce the forts of Verdun at all costs, even as German artillery killed their men in ever-increasing numbers. The French, in turn, focused their artillery on the same battlefield, aiming at German soldiers and artillery pieces. While the German guns were larger and had longer range, the French 75 mm guns could fire with accuracy at a higher rate of fire.

What resulted was a horrific engagement where hundreds of thousands of soldiers died on either side — almost in equal ratios on both sides. Four fifths of the casualties on both sides were caused by the shelling, but by small arms fire or air power. Above it all, aiding the artillery barrages, were the reconnaissance and spotting aeroplanes that flew for each sides.

The Fokker Scourge, to the great extent, was important because so many British and French artillery spotting and reconnaissance planes fell to the Eindeckers. Over Verdun, this was critical as it blinded the artillery and reduced its effectiveness. With the arrival of the Nieuport 11 Bébé, the situation was destined to change.

The Guardian of Verdun

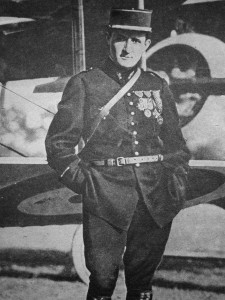

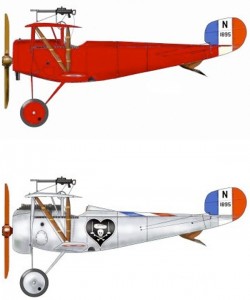

From the first months of 1916, Nieuport 11 Bébé fighters were dominant wherever they were found. By the late Spring of 1916, sufficient numbers had been delivered to French squadrons that the Germans began to feel the effects. Over Verdun, among the many Nieuport 11s, one stood out. In a move that would foreshadow by nearly a year the “Red Baron”, Manfred von Richthofen, one French pilot, Jean Navarre, painted his Nieuport 11 Bébé bright red. He soon was racking up kills over German reconnaissance and artillery spotting planes.

Like all aces of World War I, Jean Navarre and others in their Nieuport 11 pilots — including the Americans in their new Lafayette Escadrille (which was equipped with the Nieuport 11 Bébé at the outset) — lived hard, often short lives. Navarre was soon declared the “Guardian of Verdun”, a title that he enjoyed during his frequent visits to Paris with another of the French Nieuport 11 Bébé aces, Charles Nungesser, who was called “The Knight of Death” (his plane carried a black heart emblazoned with the skull and crossbones).

By the end of 1916, Charles Nungesser had scored 21 kills in his Nieuport 11 Bébé against the Germans. With many injuries from past combats and crashes, he had to be lifted into the cockpit since his legs were too weak. Together, Nungesser and Navarre would often travel to Paris in the evenings and weekends, frequenting cafes and restaurants, drinking and flirting with girls. Sometimes, Nungesser would return to the airfield for a mission still dressed in his evening wear, a beautiful woman hanging onto his arm. He was the epitome of the dashing, young French ace.

Another French ace who cut his teeth in the Nieuport 11 during 1916 was Georges Madon, who, when he transitioned to SPAD VIIs in late 1916, had already scored 25 kills against the Germans (his final score was 40) in the Nieuport. Likewise, Maurice Boyau, the rugby athlete who flew with the French squadron known as “Les Sportifs”, flew the Nieuport 11 and its upgraded successor, the Nieuport 17, for much of his career. He ended the war with 35 victories. René Dorme, another Nieuport pilot, claimed 43 German aircraft downed, but was credited with 23 officially. Likewise, Gabriel Guérin, another Nieuport pilot, scored 23 kills. Other Nieuport high-scoring aces included Alfred Heurtaux, Albert Deullin, Henri Hay De Slade, Bernard Barny de Romanet, Armand de Turenne and Gilbert Sardier. Many of these names are virtually unknown today even in aviation history circles, yet at the time, they were the great airman who took back control of the air from the Germans in 1916.

Final Notes

With the Nieuport 11 Bébé, the Fokker Scourge officially ended. Other Allied aircraft no doubt played a part as well, such as the new DH 2 biplanes of Britain, which solved the forward firing gun problem by using a pusher propeller so the front field of fire was unlimited. Yet it was the Bébé that forced the Germans to reevaluate their air tactics and embark on the development of new, higher powered aircraft. The result, predictably, was the beginning of a long series of moves and counter moves as each side learned from the other, improved, rearmed and reequipped with ever newer, more powerful planes. Yet for all that, the ground war was the dominant theme of World War I. More men died in a week on the ground than in the entire four years of the war in the air.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Many pilots in history carry mementos or favors into combat. Sometimes these are photos of their wife or girlfriend, other times they are “lucky” devices meant to safeguard them from harm (a rabbit’s foot, a lucky rubber band around the wrist, etc.). Yet Jean Navarre piloted his Nieuport 11 Bébé with a piece of very special memento. As noted, the charismatic pilot, who was the toast of Paris and a regular in the nightclubs, had many ladies following him about. Thus, in combat while flying his Nieuport (and later in his SPAD), he wore a woman’s silk stocking tied onto his head — yet another reminder of his many conquests in Paris, no doubt. Whether the silk stocking was given to him by a woman, purchase or just taken as a “trophy” has been lost to history.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Did any American pilots in the Lafayette Escadrille score kills in the Nieuport 11 Bébé — which?