Published on January 13, 2013

One hundred and one years ago today in aviation history, on January 13, 1912, a Frenchman named Jules Védrines set out from Pau in a new aircraft, a Deperdussin that had been purpose-built for speed. His flight broke records for the 150 kilometer distance, yet another achievement for the famous aviator. This was not the first such flight Védrines, however. In fact, five months after earning his flight certificates at the Blériot School, he competed in May 1911 and won that year’s Paris to Madrid Air Race. However, it would not be that race that would earn Jules Védrines his place in history — rather, it was something that he did later in a fat, ugly aeroplane named “La Vache” (which translates from French as “The Cow”) — and, in so doing, he helped create an entirely new field of military aviation operations.

Fastest Man Alive

The 1911 Paris to Madrid race was Jules Védrines’ first great speed challenge. After wracking up his own aeroplane, he would fly a borrowed Morane-Borel monoplane that belonged to a Belgian aviator named John Verrept. In that race, Jules Védrines managed the flight in just 12 hours and 18 minutes of flight time spread of 37 and a half hard hours. Shockingly, he was declared the fastest not because of his flight times and speeds, but rather because he was the only finisher in the grueling race. It was a terrible race, as a take off accident by another pilot ran into the assembled VIPs at the side of the field, killing France’s Minister of War.

Where others dropped out, he proceeded — five others also set out, but one by one came down with engine problems. In the end, he collected a sizable cash prize and was also awarded the Cross of the Order of Alfonso XII, which was to be hung around his neck by none other its namesake, the King of Spain. After the hard flight, however, Védrines was irritable and surly, probably due to exhaustion. Worried about his mood, however, the Spanish had him examined by a group of doctors to assess his mental balance and stability before they allowed him an audience with the King.

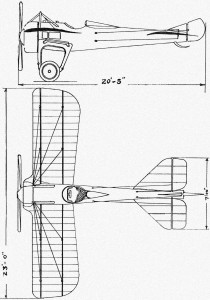

A year later, he would prove his racing credentials during speed tests in the Deperdussin monoplane in 1912. That aeroplane, carefully designed to limit profile drag and fitted with a powerful engine, was the ideal steed for record-setting flights. Within the next few months, he became the first man to break the magic number of 100 miles per hour — racing at 105 mph to take the record as the fastest man alive.

La Vache at War

With the outbreak of the Great War of 1914, Jules Védrines joined the French Armée de l’Air, as did many other French citizen aviators such as Roland Garros, Eugène Gilbert and Adolphe Pegoud. Many of these already famous men went on to even greater fame during the war — usually by shooting down enemy aircraft and thereby becoming France’s first aerial aces. Yet Jules Védrines did not achieve fame as a fighter pilot, though he did fly that role too. Rather, he did so in an unlikely, ungainly, fat and ugly aeroplane that he had privately built and named, “La Vache” in honor of his homeland in France’s cow country of rural Limousin.

“La Vache” was painted milk white and emblazoned with its name in large letters on the side of the fuselage. With the onset of war, he pinned on his military wings and brought his aeroplane into the service of France. “La Vache” was now a warplane — a role that it had been originally designed for by the Blériot factory, who had armored it for military use. “La Vache” was powerful too, sporting a 160 hp Gnome engine.

With the first months of combat, fighter planes were yet to be developed and deployed and most aeroplanes flew reconnaissance missions and artillery spotting. For this role, his two-seater was ideal. From early on, Jules Védrines became an expert reconnaissance pilot. In the summer of 1915, he received an award for having survived 1,000 reconnaissance and special air missions against the Germans. By then, the agile Fokker Eindecker types had taken to the skies and began the Fokker Scourge — they made short work of the unarmed, slow flying reconnaissance planes. Védrines recognized the dangers looming ahead for him if he continued flying such missions.

The First Special Forces Pilot?

Being a famous aviator from the pre-war period, Jules Védrines had the liberty of changing his mission and role by his own decision, so long as those above approved it. He recognized with clarity that if he stayed in reconnaissance, it would not have been long before a Fokker would shoot him down. Further, he could see that the French Armée de l’Air was training and deploying new reconnaissance aeroplanes — his mission could be flown successfully by the hundreds of others now in flight training and deploying to new squadrons.

At first, he flew some fighter missions, using the new metal deflector plates on the propeller that Garros would make famous. Then, on his own initiative, he volunteered “La Vache” and himself for an even more daring mission. This would involve a night operation that would have him flying across enemy lines into the German army’s rear, where he would land and secretly drop off and pick up agents for special operations, serving as a frequent covert operations pilot. In this role, “La Vache”, a two-seat aeroplane, performed admirably and reliably. Despite the extreme risks entailed by flying numerous secret nighttime missions, always under threat when landing behind German lines, Jules Védrines would survive the war.

Ultimately, it might be said that Jules Védrines was both the fast and the luckiest man alive.

One More Bit of Aviation History

Eugène Gilbert, who participated in the 1911 Paris to Madrid Race against Jules Védrines, should be a better known name in aviation history for a number of reasons — chiefly, it was he, not Garros, who invented the deflection plate fitted to the prop that allowed his Morane’s machine gun to fire straight ahead. Yet another story, however, also captures the incredibly history of Gilbert. In this little known story, Gilbert put a whole new meaning to the term “bird strike”.

During his crossing of the Pyrenees while in the 1911 race to Madrid, Gilbert and his aeroplane were attacked by an eagle which repeatedly struck the aeroplane and tried for Gilbert himself as well. Apparently, the eagle objected to manned aviator — or maybe perhaps Gilbert had come too close to its nest or chicks. In any case, the eagle made repeated attacks, nearly forcing Gilbert down. He was only able to escape by taking out his revolver (aviators crossing Basque country were smart to be armed) and firing a series of shots. He intended to miss, hoping that the reports would scare off the eagle. Thankfully, it worked and he flew off, leaving the eagle behind. Nonetheless, Gilbert would come down later and not make it to Madrid.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The Deperdussin 1912 racer featured an interesting wing plan, with the chord lengthening (widening) steadily in a sweep back of the trailing edge toward the tip. What was the perceived advantage of this design at the time?

Less turbulence for the tail.

Interesting claim and it may be true, however, I find no contemporary claim that matches that. Other guesses?

Because it used wing warping, the outboard part of the wing would travel more than the inboard. This increased area on the outboard wing would give more roll control.

That’s one of the reasons given at the time and it has some merit aerodynamically. There were several other reasons given as well — at least one other with true aerodynamic merit. Anyone?

OK, how about these:

Better downward vision. Less drag due to smaller wing to fuselage intersection [ used on gull wing Stinson and Whitman Tailwing]. Ease of access to cockpit.

Fascinating and great, if unexpected answers. However, once again I find no reference in the contemporary reviews of the aeroplane. Other ideas and thoughts?

The narrower chord is within the slipstream of the propellor so it was an attempt to avoid creating a bump in the lift over the wing behnd the prop, lower drag in other words as there is less wing in the faster airflow.

It would not be effective since the slipstream effect is small at high speed and the dip in the spanwise lift distribution due to the fuselage is always detrimental. This would make it even worse.

Good site, just a thing, it was not Eugène Gilbert but Louis Gibert who was a concurrent of Jules Védrines in 1911 Paris-Madrid race, and the eagle attack is a fake, the idea came from Louis Gibert in a communication with Jules Védrines, Roland Garros and Alfred Leblanc (Blériot team manager) at San Sebastien the day before the third step San Sebastian – Madrid, in order to have fun of two journalist who were a little too embarrassing with pilots, the fake works so well with Louis Gibert and Jules Védrines that it was taken for truth and made the first page of newspapers !

Regarding the creation of the defection plates, several men were involved, Gilbert, Garros but mostly Raymond Saulnier the genial co-designer of Blériot XI, then designer of the Borel-Morane (flown by Védrines in 1911) then the Morane-Saulnier.

About Védrines missions, his very first one was a night mission on 3rd august 1914 around Paris to fight an hypothetic Zeppelin that never show up, but it was very probably the first war night misson in history, probably done on a Blériot type XXXIX (39), only armed with some hand grenades.

All his special missions, 8 in total, were not done between april and september 1915, with the Blériot “La Vache” but with a Morane-Saulnier MS type L. “La Vache” was destroyed at Tours the 5th of october 1914 by accident, when he came back, after the Marne battle at the rear of the front in the aviation reserved for insubordination. His story is not simple…

Thierry Matra

Author of “Jules Védrines 250 000 km in Aeroplane”