Published on January 30, 2013

It was January 1911 and in Cuba there was much talk of aviation. News reached the island with frequency about the great flights underway at Palm Beach by Glenn Curtiss and his pilots. Yet only one airplane had ever flown in Cuba and that had been a brief attempt that had ended badly when Frenchman André Bellot crashed his 60HP Voisin biplane at the Almendares Hippodrome eight months earlier on May 7 1910. Answering popular demand, the City of Havana and the Havana Post together invited Glenn Curtiss and his pilots to perform an airshow.

To sweeten the pot, the city and newspaper offered the princely sum of $8,000 to the first aviator who could fly from Key West, Florida, to Havana — a princely sum that today equates to approximately $200,000 adjusted for inflation. J. A. Douglas McCurdy, a Canadian, saw the value in it, despite the risk, and volunteered to make the attempt. The flight would be more than 90 miles, in other words, the farthest distance over water ever attempted. It would not end well.

J. A. Douglas McCurdy

Who was this dashing, young, trim aviator who was daring enough to accept the challenge? Douglas McCurdy was not a newcomer to aviation. In fact, he had been one of the few men involved in Alexander Graham Bell’s famous Aerial Experiment Association. Starting in 1907, the AEA had pioneered the development of the first successful airplane to fly in Canada. On February 23, 1909, Douglas McCurdy himself would take out his design, the Silver Dart, onto the ice at Bras d’Or Lake in Nova Scotia. With a crowd of disbelieving Scottish Canadians looking on, he started the motor and took off. Thus, he became the first to fly in Canada and the first man to fly in all of the British Empire (including in England itself!). Later, he was awarded the first pilot license in British history.

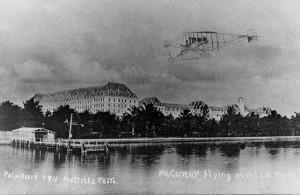

After his achievements in Canada, he made a number of exhibition flights in New York before coming down to Florida with Glenn Curtiss, another former member of the AEA, where they set up shop flying exhibitions while Curtiss developed his airplane business (and later real estate business, which included founding the cities of Hialeah and Opa Locka). With a Curtiss Biplane, McCurdy was soon a regular feature of the American flying circuit and would undertake many exhibition flights over the Palm Beaches.

Preparations for the Cuba Flight and Airshow

The draw of winning the prize was large and so the US Navy stepped in to support the project. On the day of the flight, they would put a chain of six Naval ships stretching the entire 90+ mile distance to Havana, each one within sight of the next. The ships would run their boilers and belch smoke into the skies to signal the pilot. Thus, if McCurdy could get off, he would just have to fly from ship to ship until he arrived — and if he crashed, he would be within sight of at least one and maybe two of the ships. McCurdy prepared a Curtiss Biplane at Key West for the flight.

The upcoming airshow over Havana would involve two other airplanes that were shipped ahead by boat. Three other pilots accompanied the planes to Havana, which was scheduled to be performed on January 31, 1911. As for McCurdy, he planned his departure from Key West on January 24. However, the weather and winds did not cooperate. Day after day, the gusty conditions blew strongly out of the north. Finally, the day before the scheduled airshow, on January 30, 1911 — today in aviation history — the winds calmed somewhat and he announced that he would go.

For safety, he had a set of tin cylinders mounted on the wings of his biplane to serve as lightweight floatation devices. If he crashed, he hoped that these would keep the plane afloat for precious minutes until the Navy could pick him up.

The Flight to Cuba

At the appointed hour, Douglas McCurdy climbed into the cockpit of his Curtiss biplane. A huge crowd had gathered at Key West to see him off. Before flying across the water, however, he decided to do a check out flight. Thus, he started the engine, taxied out and took off for a brief flight around the field, intending to land. As he circled back, however, he saw that spectators had rushed onto the field, making a landing impossible. With a shrug, he had no choice but to continue on to Cuba. He had sufficient fuel and the engine sounded fine. He pointed the plane south and spotted the first Navy ship in the distance. In all, six US Navy torpedo boats would span the distance to Havana, spaced approximately 15 miles apart. At Havana’s harbor, several other US Navy torpedo boats would be at anchor.

Douglas McCurdy climbed to 1,000 feet of altitude and soon the plane was cruising along at a nice pace (later figured out to have been 48 mph). Later he recalled the scene perfectly — “It was a brilliant morning and as I flew over the intense blue water, I felt a thrill of happiness and contentment known only to those who have delighted themselves by this form of travel.” Also, he added, “Out on the water, I could see the smoke from the funnels of the nearest torpedo boat. Half a mile out, I saw a beautiful mirage before me over the water. It was magnificent — words fail me to describe it.”

The End of the Flight

Everything worked perfectly for two hours, when he reached Havana. Within sight of the harbor, he could see a huge crowd had gathered along the Malecon, Havana’s famous waterfront. They were cheering and pointing — clearly they could see him as flew in. He was elated — he had made it, or nearly so….

Then there was a loud bang. He twisted back to look at the engine. Several more bangs followed in quick succession and the engine stopped abruptly. The propeller hung motionless and he realized that the cylinders had blown out. There was nothing to do but glide toward the water. On the shore, thousands of Cubans pointed and yelled — they could see that he was bound to crash. The US Navy torpedo boat USS Terry (DD-25; a Paulding class vessel) raced to the scene and fished McCurdy out of the water, though the plane was a complete loss. As it happened, McCurdy never even got his feet wet.

The following day, after much discussion, the City of Havana and the Havana Post decided to hold an awards ceremony to give the check to McCurdy — after all, he had made it into Cuban waters. McCurdy graciously received the envelop amidst speeches and crowds, but found out back at his hotel room that the envelop was empty — perhaps some corrupt Cuban Government official had made off with the prize after all.

Though Douglas McCurdy would never receive his prize, to the end of his days he described his flight to Cuba as his greatest achievement — that’s saying alot for a man who held Pilot License No. 1, had invented Canada’s first airplane, and had guided Canadian aviation, including military aviation over the following nearly five decades.

One More Bit of Aviation History

From January 28 to 31, 1911, the airshow over Havana took place, with the first flight by Jimmie Ward in winds that gusted upwards of 30 mph. “All of Havana” witnessed the event. After the arrival of McCurdy on January 30, the following day, they would fly a full show, putting two aircraft into the air at once, much to the delight of the Cuban people, who lined the Malecon to witness the planes once again. This time, McCurdy took off first in a 60 hp biplane and performed figure eights overhead the crowd — the event warranting an article in the New York Times, which noted:

The weather conditions were perfect for flying and an excellent exhibition was given by the aviators. McCurdy, who made the first flight today, startled the spectators by his sensational spiral twists, tilting his biplane over to a steep angle above the heads of the crowd, and reversing. Then he sailed close to the ground above the heads of the people and soared up again and cut figure eights at a considerable height.

A slight accident occurred while McCurdy was giving his exhibition. It was discovered in time and did not have any serious result. A strip of canvas which was torn off the upper plane streamed back, endangering the propeller, but McCurdy managed to land his machine safely.

After tearing off the loose canvas and examining the upper plane of his machine, McCurdy decided that the damage was unimportant and that the biplane was in condition to be safely used again. [Lincoln] Beachey went up in the same machine and circled the field for sixteen miles. He was followed by [Jimmie] Ward, who made a fine flight, rising 1200 feet in circles of six or seven miles. He went out over the sea for half a mile, remaining in the air for thirty minutes and descending with a magnificent glide during which he dipped under McCurdy, who was flying at right angles to him.

On February 5, McCurdy made yet another flight — this time from the US Military Camp of Columbia to the Morro Castle, using the 60HP Belmont biplane, one of the two planes that the team had brought to Cuba. As it happened, all of the pilots were celebrated by the Cubans everywhere they went, and none more so than Douglas McCurdy himself.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

What pilot made the first successful flight between Cuba and the United States, in either direction, and when was it achieved?

This achievement is not well known on this side of the Atlantic. McCurdy’s crossing was less that two years after Louis Bleriot made the much shorter crossing of the Chennel. Interesting to see the advance…….

Truly such a wonderful story. I first learned of McCurdy while at a Key West themed restaurant looking at an old plaque on the wall. While the plaque was interesting, I had no clue the incredible story behind the man and his famous crossing! Truly fine work with this article.