Published on February 28, 2013

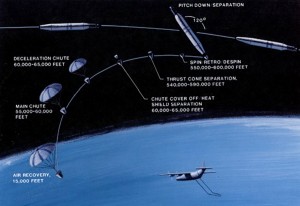

In 1959, 54 years ago today, the United States launched a secret satellite from Vandenberg AFB, California. The first of America’s spy satellites, it was to be called KH-1, or Discoverer, aka CORONA. That first successful launch, however, wasn’t exactly a spy satellite, but rather a small capsule without a camera or any data collection gear. It was instead designed to test polar orbit and, after three orbits (the target profile for the KH-1 series), the satellite released its film canister to reenter the atmosphere. Once the film canister was at lower altitudes, it deployed a parachute and, if all went well, a USAF airplane would snag the payload in midair and fly it back to Hawaii.

Yet, as with many early space and rocketry programs, the mission ended badly. To this day, nobody knows exactly what happened to the satellite and its capsule. The best guess? It is probably down, buried in snow and ice, somewhere near the South Pole in Antarctica. From this inauspicious start, however, America’s spy satellite programs would grow to become the world’s best and most effective in the world.

Starting from a Record of Failures

The KH-1 program was on the very bleeding edge of technical development. Everything about it was experimental, from the rockets to the capsule, to the control systems, the cameras, the film, the lens, the reentry system, the recovery canisters, the parachute system, and even the USAF recovery aircraft and its system to snag the parachute shrouds of the canister as it floated down! As a result, a lot of failures were expected. Nonetheless, the Eisenhower Administration had faith in the new US aerospace industry and in particular in Lockheed, which had responsibility for the overall project.

What followed was disheartening. A series of 22 launches were undertaken and almost all ended in abject failure. The program moved ahead, pressed forward by increasing frustration from the White House and the CIA about the lack of successes.

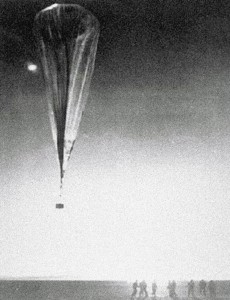

The failures were also measured against the successes of earlier programs involving non-satellite overflights, the most notable being a balloon-based camera system called GENETRIX that flew over the Soviet Union at 90,000 feet, returning full canisters of film for analysis — 516 GENETRIX balloons were flown before the program was cancelled for political reasons. The film was essential for intelligence analysts, since the Soviets were embarking on a range of new developments that included new bombers, new nuclear weapons, new rocket systems and new atmospheric and underground tests of ever larger atomic and hydrogen bombs.

The USGS published a list of failures of the program, highlighting only those missions where the KH-1 spy satellite was actually carried and thus ignoring the launches in between where the recovery system was tested. Even that reduced list reads like a disaster:

- Mission 9001 :: 25-Jun-59 — Mission failed. Failed to achieve orbit

- Mission 9002 :: 13-Aug-59 — Mission failed. Power supply failure. No recovery.

- Mission 9003 :: 19-Aug-59 — Mission failed. Retro rockets malfunctioned negating recovery.

- Mission 9004 :: 7-Nov-59 — Mission failed. Failed to achieve orbit.

- Mission 9005 :: 20-Nov-59 — Mission failed. Eccentric orbit negating recovery.

- Mission 9006 :: 4-Feb-60 — Mission failed. Failed to achieve orbit.

- Mission 9007 :: 19-Feb-60 — Mission failed. Destroyed just after launch due to erratic attitude.

- Mission 9008 :: 15-Apr-60 — Mission failed. Attitude control system malfunctioned.

With the last failure above, it was just ten days later, on April 25, 1960, that Gen. LeMay personally intervened with a formal letter to the president of Lockheed. The message was clear, get the engineering right, no matter what it took and to take the time they needed.

A New Imperative

On May 1, 1960, the situation suddenly reached a critical point. The U-2 spy plane flown by Francis Gary Power was shot down while on a CIA flight from Peshawar, Pakistan, to Norway on a path right over the heart of the Soviet Union. Facing intense political pressure and recognizing the sudden dearth of military capabilities to continue such overflights (i.e., the Soviets were likely to shoot down yet more U-2s), the U-2 operations over the Soviet Union were cancelled.

While it lasted, the U-2 imagery had provided analysts with reasonable data for the narrow flight path flown. This had allowed the US to recognize what was happening within the Soviet Union and, with good intelligence, it enabled good decision making. These were some of the most critical years of the Cold War. Yet with the U-2 program of overflights suddenly at a standstill, it was as if the lights had gone out on intelligence just when it was needed most.

With every passing week, concerns grew that the Soviets were racing ahead in their missile programs. By mid-1960, the term “Missile Gap” had come into use to describe the perceived superiority of the Soviet Union’s space and rocket programs — particularly ICBMs — over Americas. The issue became a major topic of the election race between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon in the 1960 campaign, with Kennedy campaigning on the Missile Gap issue and the need for America to win the space race. Sputnik had become a household word and a new fear was spreading across America.

Getting it Right

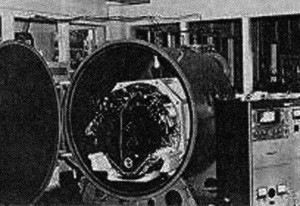

Finally, on August 18, 1960, with Gen. LeMay’s encouragement, Lockheed was ready. The launch of Mission 9009 went off without a hitch. The spacecraft, a KH-1 with a Eastman-Kodak camera on board that used newly modified film, made three passes over the Soviet Union, shooting yards of film. At the programmed de-orbit point, the film canister ejected and reentered the atmosphere. Newly developed gas thrusters got it spinning like a football to help ensure stability as it plunged toward Earth. The parachute system deployed perfectly. Here the one and only error took place — the aerial recovery plane missed the intercept completely. The film canister fell into the waters of the Pacific Ocean.

A floatation system had been designed into it so as to ensure that it could be recovered even if the aerial interception failed. A helicopter was deployed and the capsule was retrieved properly. It was loaded onto a transport plane and flown quickly to the Continental United States. Arriving on the West Coast, it then continued across to Washington, DC, where the CIA’s analysts received the package and went to work.

The results were astonishing. Resolutions in that day and age were grim by today’s standard — optimally just 35 feet — yet this was far better than anyone had expected. The negatives were spread on light tables and photo analysts went to work counting Soviet missile sites and weapons programs. By September, the numbers were clear — there was no “Missile Gap” after all. An official cable from the CIA offered its views of the success of the KH-1 system, using terms like “terrific, stupendous” and “we are flabbergasted.” In fact, U-2 film was much higher resolution — but just this one KH-1 success produced more land coverage than ALL of the previous U-2 missions put together. The films included good imagery of 64 Soviet airfields and 26 surface-to-air (SAM) sites. Indeed, the era of satellite reconnaissance had finally been born.

Final Flight

Mission 9010 was next. It was flown on September 13, 1960. The USGS report was blunt — “Mission failed. Attained orbit successfully. Capsule sank prior to retrieval.” In other words, everything had worked perfectly, but once again the aerial recovery plane had missed the interception. This time, however, the floatation device had failed and the capsule sank into the deep of the Pacific Ocean.

This was to be the last of the KH-1 spy satellite flights and tests. A month and a half later, on October 26, 1960, the first KH-2 mission, 9011, was flown. Not surprisingly, it too failed. The report, characteristically, was crisp in its assessment: “Mission failed. Satellite failed to separate from booster. Failed to achieve orbit.” Yet from this inauspicious start, American spy satellite programs would steadily expand.

In the end, the key success of the spy satellite programs during the Cold War, starting with KH-1 and continuing through KH-11 (and beyond to today), was not that we could photograph the proverbial license plate of the enemy, but rather the simple lesson that with knowledge comes stability. The Soviets too developed their own spy satellites. Soon, a tacit agreement emerged between the two countries — neither would shoot down the others satellites.

In the end, KH-1 was the beginning of the carefully developed understanding between America and the Soviets, one that would allow the world to avoid a nuclear catastrophe that would have taken place had World War III broken out. Ultimately, that’s not a bad record for a satellite system that was experienced its own long chain of disasters.

Good writing makes for good reading. My friend Carl Overstreet was the first pilot to fly an operational U-2 mission over Eastern Europe. He has always wanted to see some imagery from one of his missions. Is there any possible way to do this? Carl lives with his wife Elizabeth in Bedford, Virginia. He remains a remarkable man.

I came for information about the KH-1 and this article featured an image from the satellite. Thanks a lot for that!

I am wondering if there are any more images available from the KH-1 that anyone might have?

The imagery from the KH missions has been declassified and is available through the USGS at their website http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/