Published on March 24, 2013

The Aerial Transit Company was established and incorporated in England “to convey letters, goods and passengers from place to place through the air….” With the documents filed, as well as a patent for some of the technologies that they had developed to support the venture, the four partners set out to raise the necessary funds to launch. An advertising campaign was developed with posters designed to highlight all of the beautiful destinations that could be visited. These ran in newspapers, magazines and were handed out to the press in hopes of generating public interest and investor support for the venture. Despite the promise of the business model, however, acquiring start-up funding proved difficult.

This story probably sounds familiar, all the more so because it has been repeated thousands of times over the years with each new commercial airline venture. here is one main difference, however — the Aerial Transit Company was founded in 1843, six decades before the Wright Brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk.

The Founders

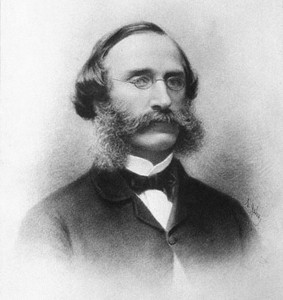

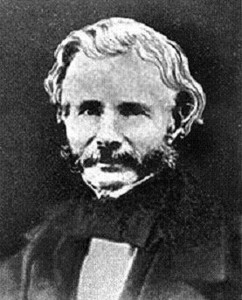

The idea of a powered aircraft that could be steered and carry more passengers than a balloon was the brainchild of William Samuel Henson, born in 1812 and a seasoned businessman from Nottingham and his partner, John Stringfellow, who was thirteen years older and from Chard, where he had an established position as a proven inventor who had worked in lace factories and had pioneered compact electric batteries.

Together with two other men, they established established the world’s first airline company — though they were armed with little more than an English patent awarded for their aircraft design, which was untested. At the time, only balloon flight could hope to carry passengers to a distant destination by air, even if that was unpredictable, challenging and slow. With visions of supplementing their income with flights that carried cargo and mail, as well as passengers to distant places — as far away as China, spanning the entire British Empire — the partners were true visionaries.

The Aircraft

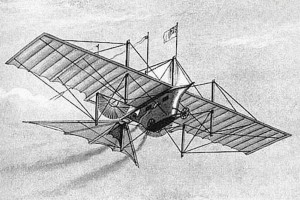

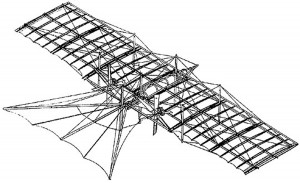

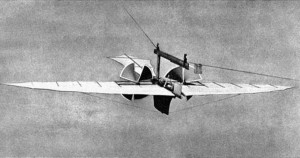

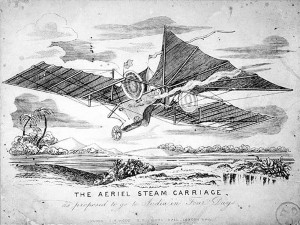

The passenger carrying monoplane was to be called the “Ariel” and would be powered by a small, highly engineered steam engine that turned two six bladed propellers mounted on the wing (today, this would be called a conventional twin). The aircraft was to be truly huge, capable of carrying 10 to 12 passengers and having a wing span of 46 meters (150 feet). It was projected to weigh in at 3,000 pounds and have a maximum range of 1,000 miles. To achieve that, Henson and Stringfellow had pioneered a whole range of other inventions.

Their monoplane design featured a wing with a proper airfoil and covered surfaces top and bottom. A hollow main spar with leading and trailing edge boards, were held together by a series of wing ribs to establish a proper airfoil. As well, wires affixed to posts gave further support to the wing as it was foreseen that the forces of aerodynamics could be significant and that this allowed overall lightening of the airframe. Even the methods of holding spars and ribs together were defined and finely researched. A tricycle gear configuration was pioneered for take off and landing as well as a launch rail that would allow the plane to maintain a heading as it accelerated to flying speed.

For control, Henson envisioned a elevator and rudder — ailerons or wing-warping were not pioneered with this design. In his own words, describing the control mechanism in his patent, Henson and Stringfellow wrote:

…in order to give control as to the upward and downward direction of such a machine I apply a tail to the extended surface which is capable of being inclined or raised, so that when the power is acting to propel the machine, by inclining the tail upwards, the resistance offered by the air will cause the machine to rise on the air; and, on the contrary, when the inclination of the tail is reversed, the machine will immediately be propelled downwards, and pass through a plane more or less inclined to the horizon as the inclination of the tail is greater or less; and in order to guide the machine as to the lateral direction which it shall take, I apply a vertical rudder or second tail, and, according as the same is inclined in one direction or the other, so will be the direction of the machine.

The Experiments

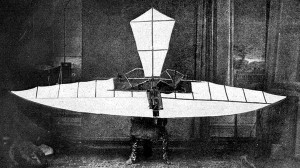

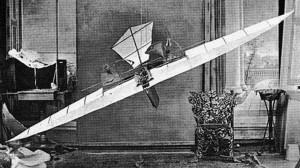

Together, William Henson and John Stringfellow proved a basic aircraft design by tests with a flying model that featured a wing span of three meters. After adjustments, it successfully flew multiple times in 1848. John Stringfellow’s connections in Chard allowed the pair to use a shuttered former lace and bobbin factory there for their experimentation. To help launch the model, a launch rail was inclined upward so as to give some upward trajectory at launch — the launch rail spanned approximately half the room (about 10 yards). At the far end of the factory floor, fully 22 yards long and 10 to 12 feet high, a canvas tarp was freely hung so as to stop the test model from crashing into the wall. The tarp would soften the model’s impact and leave it largely undamaged, arresting all forward motion, whereupon it would fall to the factory floor.

John Stringfellow’s son, Frederick, related the progress and detailed the names of those who witnessed the successful tests:

In the first experiment the tail was set at too high an angle, and the machine rose too rapidly on leaving the wire. After going a few yards it slid back as if coming down an inclined plane, at such an angle that the point of the tail struck the ground and was broken. The tail was repaired and set at a smaller angle. The steam was again got up, and the machine started down the wire, and, upon reaching the point of self-detachment, it gradually rose until it reached the farther end of the room, striking a hole in the canvas placed to stop it. In experiments the machine flew well, when rising as much as one in seven. The late Reverend J. Riste, Esquire, lace manufacturer, Northcote Spicer, Esquire, J. Toms, Esquire, and others witnessed experiments. Mister Marriatt, late of the San Francisco News Letter brought down from London Mister Ellis, the then leasee of Cremorne Gardens, Mister Partridge, and Lieutenant Gale, the aeronaut, to witness experiments.

Sadly, as the two men attempted to pioneer ever larger models of six meters to prove its flight characteristics, they were to be gravely disappointed. As they scaled up the design, the weight of the steam engine was not quite overcome by the lift of the wing. Despite other experiments, they were never able to fly a larger test model than the three meter design.

Seeking Funding with an Advertising Campaign

Despite the failure of the six meter model, with a successfully flying smaller model, the four partners to seek out funding. The other two men in the four partner business were Frederick Marriott, and D.E. Colombine. The former served as the company’s publicist while the latter helped seek funding, including from British Government sources.

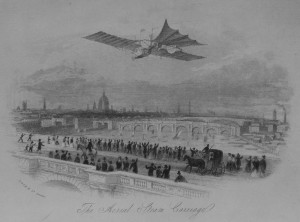

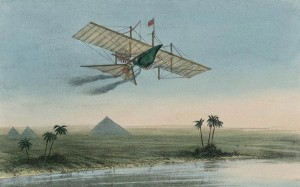

Posters depicting the Ariel flying over famous sites, such as the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt and over India were soon distributed to the press. The images received widespread coverage, to the point that the machine’s shape and supposed flight exploits (most didn’t understand that the larger version had yet to fly anywhere, even in England) became fixed in the public mind. As funding proved elusive — despite the flights of the three meter model — the four partners slowly ran out of money and ultimately interest as well. The press finally turned on the company and the founders, making claim that they were fraudsters. While false, the charges certainly complicated their task of raising funds. Finally, the project was abandoned — both the technology and the public were not yet ready for flight.

Final Thoughts

In later years, the many pioneering innovations of William Henson and John Stringfellow would inspire countless other experiments and designs. The main wing design would be proven as would the control system in the early days of flight in that heady first decade of the 20th Century. In fact, the basic wing design, replicated into the Blériot and Taube, Eindekker, Morane and Demoiselle, would remain in use into the first two years of World War I. In many ways, Henson and Stringfellow got it right — not just in technology, but even in their business model, which saw revenue from mail, cargo and passengers alike, and even military troops! Their Achilles heel was simply that the weight of a steam engine, no matter how well they engineered it, was simply too heavy to fly. To truly have enough power and fly would require internal combustion engines powered by gasoline. For that, another six decades would have to pass.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Where can you see on museum display the three meter model created and flown by Henson and Springfellow?

I recently acquired a lithograph of “The Aeriel” flying over London. I’ve never heard of this company and was impressed by how forward thinking these men were. I was wondering if the print I have is rare. I would be glad to receive any input I can get. Thank you!

Bob Kline

I have just bought a lovely print of the Ariel flying near the Giza pyramids. It is the same image shown above in this web page, but the quality of my print is higher. It is a nice print and the story behind is unique, but it still a niche item.

Gian Luca Burci

If anyone is interested in selling original period lithographs of the “Ariel” or other items related to the Aerial Transit Company please contact me I’m interested in buying. Thanks!

I have an original of the Aerial Transport Company airplane over London, if anyone’s interested.