Published March 27, 2013

When Captain Berry H. Young, USAF, took off that day in 1954, he had no idea that the events to come would test every ounce pilot skill and luck he had. An experienced Aircraft Commander with the Strategic Air Command’s 9th Bomb Squadron of the 7th Bomb Wing flying from Carswell AFB, Texas, he commanded one of SAC’s most famous planes, the Convair B-36H Peacemaker. At that time USAF history, the B-36 fleet was the backbone of SAC’s strategic bombing fleet, giving the USA the global reach to carry nuclear bombs over the Soviet Union. The day’s flight was a routine mission when he took off into history on March 27, 1954 — by the time he landed, only three of the great plane’s ten engines were still operating.

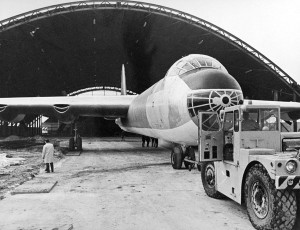

The B-36 Peacemaker

By 1954, the Cold War was in full swing. The Korean War was winding down — though it would never truly end, a conflict that remains officially still underway 60 years later — and the USAF carried the weight of nuclear deterrence against the Soviet Union. Rockets capable o carrying nuclear weapons, the so-called ICBMs, were still a distant dream. The projection of power was primarily by air, with the Soviets and the USA both vying to create more powerful, longer range and faster heavy bombers. The king of the USAF’s bomber fleet was the Convair B-36.

Equipped with six 3,800 hp R-4360-53 radial engines diving pusher propellers and four J47-GE-19 jet engines mounted outboard near the wingtips, the H model was one of the newer, most advanced models of the B-36. With two bomb bays and other modifications the plane could carry the largest thermonuclear warheads in the SAC arsenal. It was called the “Aluminum Overcast” within SAC due to its huge size, dwarfing the B-29 Superfortress of World War II fame. Though it had no aerial refueling capacity, it could take off from within the USA and hit targets across the Soviet Union due to its extremely long range.

Trouble in the Air

It was March 27, 1954 — today in aviation history — when Captain Young’s B-36H Peacemaker suffered its first inflight problems. Fuel systems malfunctions, engine issues and carburetor icing were common on the B-36 fleet and many had been landed with one or more engines shut down as a result. Yet this time, the B-36 had a particularly terrible twist in store for the crew. All three of the big radial engines on the right wing failed while in flight. Further problems developed quickly and soon Capt. Young had to shut down all four of the jet engines on the outboard of both wings.

Asymmetric thrust was a serious problem, with just three engines — all on the left wing — still functioning. The plane was still controllable, even with seven of its ten engines shut down. Nonetheless, the failures multiplied, given the lack of electrical generation capacity and related issues. As Capt. Young steered to return to Carswell AFB, he realized as well that the flaps were inoperative, meaning that the plane would have to be landed at excessively high speeds. It would take extraordinary piloting skills to keep the plane aloft, let alone make a landing. There would be no going around either — with just three engines still turning, there was no way to climb.

Incredibly, Capt. Young brought the plane within sight of Carswell AFB and lined up for a landing on the long runway. At that point, however, two of the propellers on the right side, where all of the engines were inoperative, began to windmill in the free air. This created a huge amount of additional drag on the plane and without electrical power, Capt. Young was unable to get them featured. Problems continued to mount in unexpected ways — who knew what else could possibly fail next? As the B-36 neared the runway the crew realized that the landing gear also were not working properly. With the runway looming, the crew went to work lowering the gear through the emergency system, only just getting the wheels down as Capt. Young crossed the threshold.

Yet still, the touchdown was perfect and the huge bomber came to a stop on the runway. Was it luck? Was it skill? Most likely, it was both.

Aftermath

In the weeks after the event, Capt. Young and his crew were honored for what was called the “Miracle Landing”. Few other pilots made any claim that landing the plane with so many engines out was even possible, let along to have pulled it off perfectly. In recognition of the extraordinary skill required, the crew were honored to receive the Carswell Crew of the Month Award as well as citations pinned on personally by the Command-in-Chief of the Strategic Air Command, General Curtis E. LeMay.

Just one year later, the first Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers arrived to SAC. The era of the B-36 was coming to an end — and it was high time. Though the plane never dropped a bomb in anger, it had served as a credible, capable bomber, earning it the other, more positive nickname, “SAC’s long rifle”.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The B-36 Peacemaker fleet continuously suffered from engine problems — it was often said that the plane flew with “two turning, two burning, two smoking, two joking, and two more unaccounted for.” What were the major causes of engine troubles?

The ‘pusher’ configuration of the engines in the B-36, was chosen to prevent disruption of airflow across the wings, by the large propellers. This however did not give sufficient cooling air to the engines and this resulted in the engines overheating and catching fire.

Having pusher engines, carburetors tended to ice up, causing engine fires. For example, there is B-36B Serial 44-92075, whose crew abandoned this bomber over Canadian soil on 13 Feb 50 after three engines caught fire. Prior to jumping they dropped a Mk IV nuke that the US Air Force had on loan for cold weather testing.

By the way, Capt. Berry H. Young was was not the only pilot to land a B-36 with three engines out. On 19 Jul 49, Capt. Harold L. Barry, A/C of 44-92075 successfully landed another B-36 (Serial 44-92035) on three engines and a portion of one wing missing.

For more details see my book: “Lost Nuke — The Last Flight of Bomber 075”

ISBN 978-1-926936-86-4; Heritage House Publishing, 2012.

Icing carbs do not cause engine fires — reduced power, stuck throttle, carb heat will clear it.

Your cover airplane, B-36 S/N #492033, seems to have lost it’s four jet engines.

Where did they go?

Jim A., Tucson, AZ

The aircraft shown is a B model, before the four outboard jet engines — two on each wing on a single center pylon — were added to give a speed boast to the otherwise slower basic B-36 design. We posted a B model image as the main cover just because it was quite a beautiful photograph — we apologize for the confusion that this might have inadvertently caused some viewers who were more attentive and noticed the missing outboard jets.

As a side note, while the jet engines were added to the design for use in a speed dash, for instance to evade Soviet fighters or penetrate an air defense system, they drank fuel very quickly. Thus, for long distance cruise, the jets were not used.

Interesting narrative from Mr. Septer. I guess things changed after 44-92075’s accident. I flew in SAC (B-52) during 60-66 and we were forbidden to jettison (intentionally) any nuclear device over land masses during peace time. If necessary, they went in with the aircraft (that was SAC Doctrine). I’ll have to read Mr. Septer’s book.

I am very well-acquainted with the B-36 Peacemaker. In fact, I have some hands-on experience too, having once fueled one up at George AFB, California, when I was based there in 1958. I’m a retired Fuels Chief from the USAF. I enjoy Historic Wings!

Thanks,

Russ

I was at an air display in Cornwall in the mid-1950s when a B-36 landed with an engine fire. It made a great extra part of the air show. My Dad was in the RAF at the time. I believe the air station was RAF St Eval. Does anybody have any history on this incident?