Published on April 12, 2013

When Bill Lancaster took off from Reggane, Algeria, ahead of him was the empty expanse of the Sahara desert. Having risked it all in an attempt to break the flying time record that linked London to Cape Town, South Africa, he was already running behind schedule. He had the nearly impossible task of making up time over a journey of 72 flight hours over just a little more than four days. Thirty sleepless hours into the trip, he should have stopped, yet he pushed on, even as French officials tried to intervene. His family had used their savings to finance the purchase of his airplane, an Avro Avian Mk.V that had been Sir Charles Kingsford Smith’s “Southern Cross Minor”, a proven long distance record-setter. He couldn’t afford to fail, nor try again. Above all, the love of his life, Jessie “Chubbie” Miller, looked to him to reestablish his reputation among pilots by setting the record — there seemed no other way for the two of them to start a new life together, particularly after the nasty business of the prior year’s murder trial….

Lancaster’s Earlier Flight

Captain Bill Lancaster had been an RAF pilot in the early 1920s, flying from airfields in India. Leaving active service for the RAF Reserves in 1927, he decided that he would put his experiences flying in Asia to work securing a name for himself as a pioneering aviator. His plan, given that as a child born in England, he had been raised in Australia, was to make a record-setting flight linking both countries. Plans, however, soon crashed into realities. He had insufficient funds to make the flight, even with free fuel offered by Shell and a specially-modified Avro Avian offered by Mr. A.V. Roe. Disappointed, he continued to search for a means to make the trip, but nobody, not his own family nor his wife’s family, had funds.

Then, by chance, he met a young woman named Jessie “Chubbie” Miller. Chubbie was a wealthy Australian woman who dreamed of flying from England to her home in Australia — she just needed a plane and pilot. With Lancaster’s wife’s permission, he finalized the plans for the flight. With Chubbie’s generous purse, he completed the purchase of his Avro Avian Mk. III with an 80 hp ADC Cirrus engine and extended range fuel tanks. They named their plane the “Red Rose”. On October 14, 1927, he and Chubbie set out together on the flight, both pursuing a dream. Ahead, the pair faced thousands of miles of rugged country across the Middle East and Asia.

What might have been a flight of a month or two of flying turned into a five month long affair — and that term is used quite literally, given that along the way, he and Chubbie fell in love. With breakdowns and various delays, including a crash that had required the plane to be rebuilt, there was ample time between flights to tour the countryside together and enjoy each others company. At the end of the trip, the pair did a speaking tour of Australia that further cemented their new bond as a famous couple, she being the first woman to make the trip by air. Clearly, Lancaster’s marriage was on the rocks.

America and Mexico

After the Australia adventure, Bill Lancaster and Chubbie proceeded together to America where she learned to fly and began setting various records on her own. Lancaster learned, however, that times were tough and flying jobs were few. Promised a flying job in Mexico, Lancaster left Chubbie in Miami. She planned on staying on the ground for a while, taking the time to work with a ghost writer named Haden Clarke who was paid to pen her story. In the long months apart, however, Chubbie soon turned her attentions to the writer instead of remaining dedicated to Lancaster. Absence, it seemed, did not make her heart grow fonder.

On hearing that Chubbie had taken up with the writer, Lancaster came back to Miami in a rush. On April 20, 1932, Chubbie, Lancaster and Clarke were together at Chubbie’s place in Miami for the night. By dawn, Clarke would be dead, victim of a gunshot wound to his head from Lancaster’s pistol. Summoned to the scene, the police arrested Lancaster and for the next three months, he remained in jail awaiting trial on charges of murder. At the outset, everyone expected that he would be convicted and sent to the electric chair.

Throughout the trial, Lancaster spoke softly, with confidence and authority. No doubt, this skill at oratory was in large part due to his experiences in Australia on the speaking tour with Chubbie. He was charismatic and came across as honest and upstanding. His claim that Clarke had committed suicide lacked credible evidence — two suicide notes were discovered even to have been forged by Lancaster himself! Despite overwhelming evidence against him, there was still the benefit of the doubt and the jury found him innocent.

Free to go, he departed for England. And thus, he had what he thought was his last chance to regain his position as a respected, record-setting aviation pioneer. He would attempt to set the new record from London to South Africa and, based on that, hopefully he would be able to return to successful work as a famous pilot — in 1932 and 1933, the world was gripped by the Great Depression. Chubbie, for her part, chose to reunite with him — all in the name of love.

The Flight into History

Bill Lancaster departed Croydon in the “Southern Cross Minor” on morning of April 11, 1933. Thirty hours later, after having had to do an unplanned refueling at Barcelona due to head winds, and then having gotten lost between Oran and the town of Reggane in the Adrar Province of central Algeria, he made yet another short stop for more fuel. On his plane, he carried no survival equipment — he couldn’t afford it. For supplies, he had just a two gallon jug of water, a flask of coffee and a couple of sandwiches. The next leg was to be to Gao.

Before he departed, one of the airport officials, Mr. Borel, begged him to not go. He could see that Lancaster was exhausted. When Lancaster insisted on continuing with the venture, despite the near impossibility of making up the nearly 10 hours of lost time due to his extra stops, Borel told him that if he was lost, they would send a car to search the dirt track that lead to Gao. Borel told him that if down, he should to stay with the plane and light flares so that he could be seen. Lancaster took off at 6:30 pm and disappeared into the gathering darkness. Just a bit less than two hours later, his plane failed him — the engine on the Avro Avian conked out. Despite his skills as a pilot, the exhausted Lancaster stood little chance in a pitch dark landing in the desert sand. The plane flipped on impact, leaving him unconscious, upside down in the cockpit, still strapped in. Though he had survived, the plane was beyond repair.

Lancaster’s Last Days

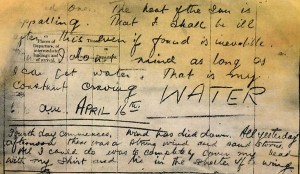

Having regained consciousness, he crawled out of the plane. With the morning sun, Bill Lancaster began to write lengthy entries in his logbook — a sort of diary of his perilous time in the desert. The first began by recounting the crash:

“I have just escaped a most unpleasant death…. It was pitch dark, no moon being up (about 8:15 p.m.). I tried to feel her down but crashed heavily and the machine turned over. When I came to I was suspended upside down in the cockpit. I do not know how long I had been out. There was a horrible atmosphere in my tiny prison with petrol fumes. By worming my way around and scraping sand away with my nails, eventually I corkscrewed my way out into the open. My eyes were full of blood which had congealed, but eventually I managed to get them open.”

With just two gallons of water, his cold coffee and the two sandwiches, Lancaster’s situation was dire. At night, he lit small scraps of fabric from the airplane and held them aloft to signal any rescuers that might come out looking for him. As it had been dark, his landing was farther from the track that Mr. Borel had said they would drive to search for him if he didn’t make Gao. How far afield of that, he did not know. He wondered whether he should set out on foot to walk east to the sea and find the track, thereby to await the passage of some traveler or his rescuer. Ultimately, he stayed with the plane, hoping to be spotted from the air.

A search was mounted, but everyone assumed that he had flown much farther south, nearer to Gao, before having crashed. None except Borel looked for a plane that might have crashed just a couple of hours out of Reggane. Lancaster’s makeshift flares of wing fabric were never seen. After eight days of diary entries, he knew the end was near as he laid down, huddled under the wing of his ruined plane. His last entry was written on a fuel card, as he had wrapped his diary into some fabric hoping that it would be preserved after he died. The note on the fuel card read simply, “No one to blame, the engine missed, I landed upside-down in pitch dark and there you are…. Goodbye, Father old man. Write Jacki. And goodbye my darlings. Bill.” (Jacki was his brother.) Elsewhere in his diary, he written to Chubbie, reflecting on his life, on her and on his “headstrong” ways that had insisted that he fly this last journey, despite the risks.

He died on the morning of April 20, 1933 — exactly one year to the day since Haden Clarke had died of a gunshot to his head.

Aftermath

So remote was Bill Lancaster’s crash site that the plane was not found for another 29 years. On February 12, 1962, a group of French soldiers came upon the wreck and mummified body of Lancaster. They found too the wrapped up diary and Shell fuel card with his final message. Taking the body to Reggane, he was buried with a proper ceremony. The diary was given to none other than Chubbie Miller, who had since remarried (in 1936) to another pilot. In 1975, the wreck of the plane was recovered and put on display at the Queensland Museum in Brisbane, Australia, left much as it was found in the desert after all those years. In recent months, it has been removed from public viewing — it remains the the testimony to Bill Lancaster’s legacy, his life and his love.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

Who set the record flight time between London and Cape Town that Bill Lancaster had so desperately sought to beat?