Published on April 2, 2013

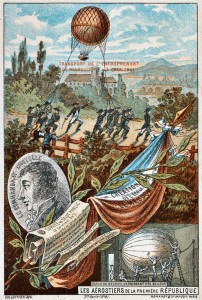

The idea was simple — observers would be raised above the battlefield to watch for enemy movements and relay them to the generals below. After careful consideration, the Government of France elected to set up a “compagnie d’aérostiers”, soldiers who would be trained in the flight of balloons, reconnaissance and battlefield observation. Initially, the command of the organization was placed under a civilian chemist, Jean-Marie-Joseph Coutelle (who was thus made Captain), and his assistant, Nicolas Lhomond (commissioned a Lieutenant). Provided with a princely budget of 50,000 livres, the two were sent to join the Army of the North and establish the world’s first “air force”. Soon afterward, an government act was passed into law, formally establishing the Aerostatic Corps — the date was April 2, 1794, and it wouldn’t be long before the unit would be engaged in battle over the forests of the Ardennes.

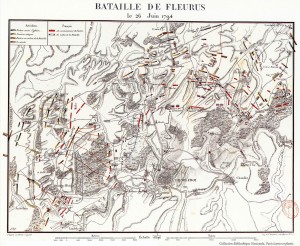

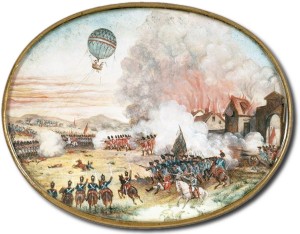

The Battle of Fleurus

On June 26, 1794, after losing Charleroi to the French army, the First Coalition — a force of Dutch and Austrians — counterattacked in an open field battle to contest the advancing French control over the Low Countries. The First Coalition was under the command of Feldmarschall Coburg, the Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, a Habsburg military general. The French forces were under the command of General of Division (MG) Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, 1st Comte Jourdan. Each army fielded approximately the same amount of men, at roughly 50,000 apiece.

The French, however, also fielded the balloon l’Entreprenant — though as the battle was about to be joined, the commanders realized that the balloon was still 30 miles from the front line. A furnace was quickly erected and the balloon was inflated on the spot. With ropes attached, the Aerostatic Corps undertook a forced march over the course of some hours, pulling the balloon along as they deployed to battle. They arrived in time to ascend and begin reporting on the battle as it unfolded. Their mission they would continue for nine straight hours, signaling messages and dropping notes with details of the movements of the Austrian-Dutch armies to General Jourdan. In a single action, the Aerostatic Corps had swept away all mystery and secrecy of movement on the battlefield — it was a technical advance that changed the very nature of warfare — or was it?

As the battle developed, the Austrian-Dutch forces swept the French flanks, yet could not hammer through the core of Jourdan’s army. With a hard counter-attack, the French brought their entire forces into play in a centered battle that was extraordinarily hard fought. Reports of enemy movements to attempt to flank and maneuver around the French army were delivered from the balloon and proved timely. Finally, the Austrian-Dutch commander, Feldmarschall Coburg, withdrew in order and abandoned the field to the French. With that, the Low Countries had fallen and the First Coalition was on course for a final defeat, which would take place two years later after additional battles and trials in the field. In later discussions, the French General Jourdan downplayed the impact of the balloon on the battle, however, writing it off as a minor matter in the outcome.

Later Battles for the Aerostatic Corps

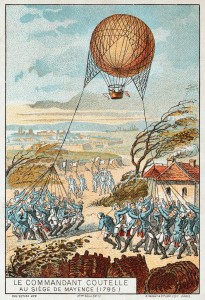

Subsequently, the Aerostatic Corps brought on two additional balloons, the Hercule and L’Intrépide and these participated in various ways in other battles, including the Battle of Würzburg when the French suffered a defeat. At that battle, L’Intrépide was captured and placed on display by the Austrians (it may still be seen in a museum in Vienna). By then, however, General Jourdan had placed his full faith in the Aerostatic Company and it participated also in the Battle of Mainz on October 29, 1795, where the balloon was launched to provide reports on Austrian movements. Though the battle was lost, the reports proved extraordinarily helpful.

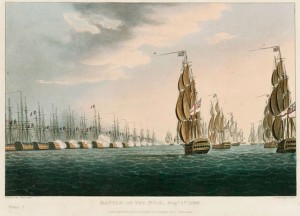

Thereafter, the compagnie d’aérostiers participated in the evacuation of Mannheim and provided observation to ensure that enemy movements were effectively blocked or avoided. Finally, in 1798, the company shipped out to Egypt to join Napoleon’s campaign there — though their balloons were lost on a ship during the Battle of Aboukir Bay, having not yet been unloaded when the British fleet descended on the French ships in the Nile.

Aftermath

In 1798, despite the success of the Aerostatic Corps, the unit was ultimately disbanded. In a weird twist of history, the future of observation balloons would be secured not in Europe but by Thaddeus S. C. Lowe in America during the Civil War. By World War I, observation balloons lined the front lines serving armies on both sides. Indeed, the very proliferation of observation balloons proved that French had gotten it right all the way back in 1795, but then had declined to press their advantage into the battles that followed.

On Sunday, June 18, 1815, the armies of Emperor Napoleon would face the armies of the Seventh Coalition at Waterloo. The key to Wellington’s initial deployment was that his forces were hidden on the back slope of a ridge, along the top of which ran Ohain Road. If only Napoleon had the services of the Aerostatic Corps, he would have known the full deployment of the enemy from the outset — and thus, history could well have been rewritten that day. Like the Aerostatic Corps, Napoleon would be banished forever into history.

Today’s Aviation Trivia Question

The Aerostatic Corps had three balloons that are well known — the Hercule, L’Intrépide and l’Entreprenant — yet there was a fourth balloon too, even if it was far less known. What was it named and what became of it?