Published on May 6, 2013

By Guy Ellis, Guest Contributor

King George VI stood in the darkened “Starlights” caravan behind Squadron Leader Brown. Together, they peered down at what seemed to be a fuzzy image on the radar’s cathode ray tube display. From his position on the ground, Sqn/Ldr Brown relayed headings and altitudes directly to the Beaufighter R while the King listened in the speaker system behind. He would guide it to within three miles, hoping to position it above and behind the target, a German night bomber. As the Beaufighter closed to within two miles of the target, he verified with Sergeant Rawnsley, the radar operator on board the plane, that he had a solid radar fix on his on his Airborne Interception (AI) equipment then he handed off the interception. If everything went properly, the rest of the interception would be done by the pilot and radar operator in flight.

Suddenly, Sqn/Ldr Brown realized that the Beaufighter was directly above their site — the Sopley Ground Control Interception (GCI) station. He turned to the King and suggested they go outside to watch the interception. Stepping out into the moonlit night, the two men lifted their eyes upward, searching for any sign of the two planes — the German plane and the pursuing Beaufighter piloted by Squadron Leader Cunningham. A faint drone from the engines was all that could be heard — then they saw something that looked like a faint red glow.

Earlier in the Night

There was little warning of the King’s visit to with 604 Squadron at RAF Middle Wallop on Wednesday, May 7, 1941. Nonetheless, everyone managed to get the airfield and into a presentable state. Accompanied by Sir Sholto Douglas, the King dined in the Officers Mess and then inspected and talked to the flight crews. For a time, the King spoke with Squadron Leader John Cunningham and then as quoted in the 604 Squadron History, he “asked Sergeant Rawnsley his score and on being told nine he commented, ‘Nine eh? Will you get one for me tonight?’ Rawnsley very much overcome by the occasion, promised to do his best. His Majesty then left to be shown around Starlight GCI at Sopley.”

It was 10:03 pm when Sqn/Ldr Cunningham and Sergeant Rawnsley boarded their Beaufighter Mk.IF (R2101 NG-R) and took off to patrol the English Channel. Their aircraft was fitted with the Airborne Interception (AI) Mk IV radar, a system that had been introduced in late September 1940 and had served the RAF’s night fighter squadrons well.

Armed with four cannon and six machine guns and with a top speed of 320 mph, the Bristol Beaufighter was a formidable night fighter, made even more so when integrated into the innovative British Chain Home radar network that looked out to sea and warned of any approaching German aircraft. The flaw with the radar network, however, was that it left a void inland. Once a German plane crossed the line of coastal radars, it disappeared into the unmonitored heartland. To address this gap, the Ground Control Intercept (GCI) radar system was developed based on a mobile system, the so-called “Starlight” caravans. The first mobile installation was established at Sopley in December 1940.

The Radar System

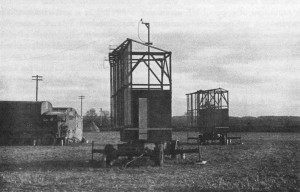

The GCI radar unit was based on an adapted Army Gun Laying tracker, known as a Type 8 Radar. This was serviced by two aerials that were aligned onto a target by two airmen, known as Binders, who would pedal a stationary tandem that operated a mechanical linkage to turn the aerials based on instructions from the operator looking at the screen. It was a crude system by later standards, but at the height of the early war period, it was the best there was.

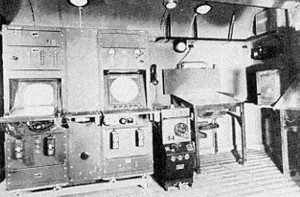

Large Crossley trucks were used to mount the transmitter and receiver each connected to an aerial, while the operations room was housed in a Brockhouse trailer. In turn, this held the crew of three — a height finder operator, a fighter controller who sat in front of the Plan Position Indicator [PPI] scope, and a plotter. Curtained off from the other crew, the plotter calculated aircraft speeds, headings and tracks of targets using a map and a Dalton computer. Sopley was also equipped with Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) system that allowed quick identification of Allied aircraft.

Integrated Radar Coverage

The mobile unit did not stand on its own, however, as initial radar contacts were provided by the Chain High and Chain Low stations that looked across the English Channel for incoming German planes. Contact information included the range, bearing, speed and height of the contact. The GCIs accepted the transferred plot and took over as the enemy aircraft crossed the coastline — from that point onward, the job was in the hands of the RAF’s night fighter units.

A high degree of skill was required to co-ordinate height, course and speed data, particularly at night. Squadron Leader Brown had with the help of Edward Bowen, a major contributor to the development of radar who personally developed the necessary control techniques. Ultimately, he would become probably the most successful GCI controller of the war.

Even with the extraordinary capabilities of the ground-based mobile GCI system, the real action typically culminated on board the night fighter. Once brought within close range, the AI operator in flight would look through a leather visor at two luminous green cathode tubes, on which he could read the horizontal and vertical positions of his target. Once in range, the echo that bounced off the enemy aircraft would appear as a blip on both screens. The operator would call instructions to the pilot, bringing the plane into visual range – from there, it was the job of the pilot to shoot down the enemy.

With Sergeant Rawnsley calling instructions to Sqn/Ldr Cunningham, the two men navigated in behind the enemy aircraft — just what type of plane it was would be a mystery until they got within visual range.

The View from the German Side

The town of Rennes in northern France served as the home of 7 Staffel Kampfgeschwader 27 (Boelcke), which was part of Luftlotte 3 within Fliegerkorps IV. That night, one of the Staffel’s bombes, a Heinkel He 111P-2 (Werke Nr 1639 IG+DR), had taken off into the cold evening air. On board were a crew of four — Pilot Oberfeldwebel Heinz Laschinski, Observer Feldwebel Heinz Shier, Wireless Operator Oberfeldwebel Otto Willrich and Flight Engineer Feldwebel Fritz Klemm. As with many in the Staffel, the men were an experienced night bomber crew.

Laschinski had joined the Lufwaffe in 1934 and had then flown for Deutsche Luft Hansa before being recalled to the new Luftwaffe for service in Spain as part of the Condor Legion. He served with distinction with 2nd Staffel Kampfgruppe 88 receiving amongst other awards the Spanish Cross with Swords, awarded for having taken part in combat missions against the Republican forces. He was then assigned as a ‘blind flying’ instructor until in 1939 when he applied for transfer to a combat group.

A Luftwaffe Night Raid

The mission that night was his 121st operational flight over Great Britain. His target was the Liverpool docks. After take off from Rennes, they had come across the English Channel at 4,000 metres (12,800 feet). Once they had cleared the flak batteries on the south coast of England, Laschinski aimed his He 111 for the Bristol Channel, intending to fly between Cardiff and Bristol so as to avoid the aerial defences of both cities.

It was a clear night and he could see the reflection of the moonlight off the English Channel as he reached down and behind to his left and found the two fuel tank transfer controls. He began to transfer fuel from the outer tanks to the inner ones. It wouldn’t be long before they would reach the Liverpool docks and, after having dropped their bomb load, they expected to return to Rennes, arriving in the early in the morning of May 7th. At that moment, they had no idea that just two miles behind, an RAF Beaufighter was steadily approaching. The German crewmen were always alert, however, scanning the darkness for a telltale flash of an exhaust fire or the silhouetting of an enemy hunter against the moon’s reflection off the water.