Published on May 19, 2013

The German Rumpler reconnaissance plane made a low altitude pass over the American aerodrome at Gengault Aerodrome near Toul, France. There, the 94th Aero Squadron, the US Army’s first combat air unit in France, was based. At first intercepted by an American pilot, the German intruder wasn’t brought down. As the German aeroplane fled toward its own base, the squadron commander, Major Raoul Lufbery, sprinted to a Nieuport 28 fighter that had been readied at the edge of the airfield. It wasn’t his aeroplane, but rather belonged to another of the pilots. While his own aeroplane was meticulously maintained, each bullet examined to prevent jamming, this was an unproven aircraft, even if of the same type as all of the 94th’s aeroplanes. Lufbery had 17 victories over the German machines and he didn’t intend on letting this one get away. Without pause, he climbed into the cockpit and the mechanic spun the prop to get the engine started.

Immediately, he took off in hot pursuit. Minutes later, the flight would end in his death.

The Final Flight

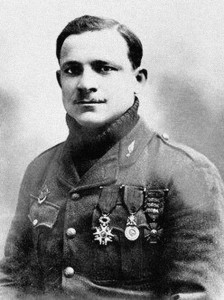

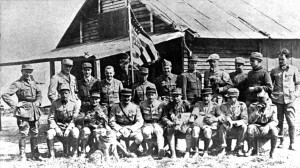

On May 19, 1918 — today in aviation history — with but six months left in the Great War, Raoul Lufbery was killed in combat. An ace with 17 confirmed victories, Lufbery was one of the early leaders of the US Army Air Corps. He was also one of the most experienced aviators among the American forces. He served as the commander of the 94th Aero Squadron, known as the “Hat in the Ring” and, from the start, he had helped train the first American pilots who had come to France. That role had started much earlier, in 1916, when he trained and commanded the first volunteer Americans flying for the French. In many ways, Lufbery was the father of American combat aviation.

The day he was killed in 1918 was not very much different from his past two years in combat. With every flight, he faced daunting odds — indeed, in some periods of that Great War, the life expectancy of Allied pilots was measured in days and weeks. He survived over two years in combat. The two-seat Rumpler reconnaissance plane he chased that final day was no easy kill. Its rear gunner could deliver deadly accurate fire against an attacker. The machine was heavy and overbuilt. It was reasonably fast, though the 94th’s Nieuport 28s were faster.

Lufbery’s victory over the German should have been fairly assured, yet it was not to be so — Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker, a man who would later become the greatest American ace of the war (based on confirmed victories), would later recount the events in detail, using Lufberty’s nickname, “Luf”:

“With far greater speed than his heavier antagonist, Major Lufbery climbed in pursuit. In approximately five minutes after leaving the ground he had reached two thousand feet and had arrived within range of the Albatros six miles away [ed. note: it was not uncommon for Americans to misidentify all German aircraft as Albatros or Fokker machines]. The first attack was witnessed by all the watchers. Luf fired several short bursts as he dived in to the attack. Then he swerved away and appeared to busy himself with his gun, which evidently had jammed. Another circle over their heads and he had cleared the jam.

Again he rushed the enemy from their rear, when suddenly old Luf’s machine was seen to burst into flames. He passed the Albatros and proceeded for three or four seconds on a straight course. Then to the horrified watchers below there appeared the figure of their hero in a headlong leap from the cockpit of the burning aircraft! Lufbery had preferred a leap to certain death rather than endure the slow torture of burning to a crisp.

His body fell in the garden of a peasant woman’s house in a little town just north of Nancy. A small stream ran nearby and it was thought later that poor Lufbery seeing this small chance for life had jumped with the intention of striking this water. He had leaped from a height of two hundred feet and his machine was carrying him at a speed of 120 miles per hour! A hopeless but a heroic attempt to preserve his life for his country!

But had it happened that way?

An Opposing View

The death of Lufbery, leaping from a flaming machine, may well have been heroic overstatement. As Royal D. Frey later wrote in his article in the November-December 1968 issue of Air University Review, eye witnesses on the ground recalled that Lufbery’s plane was not on fire at all. Rather, Lufbery had fallen from it when he had flown inverted, perhaps having forgotten that moments before, to clear a jam in his Lewis machine gun, he had undone his seat belt (as was standard practice at the time) to reach enough of the weapon and clear it.

Rickenbacker’s accounting of Lufbery’s final flight is inaccurate in other, basic ways, which leads one to question its validity. The small stream he refers to does not exist aside the village of Maron, France. Instead, the village rests alongside the much larger flow of the Moselle River. Further, the American Aerodrome at Toul was seven miles distant from the location of where Lufbery was killed — what could they have actually seen from that far away but dots in the distance, if even that?

Thus, one is led to wonder if Rickenbacker was tipping his hat one last time to the memory of Lufbery by overstating the valiant circumstances of his death. Perhaps he hoped that Lufbery’s reputation would stand the test of time better if he had died in more heroic circumstances than by an error in flight that had resulted in his falling from the cockpit. Rickenbacker need not have worried, however, because Lufbery’s reputation didn’t need any assistance — his deeds in life, far more than in death, were what truly mattered.

Afterward

Raoul Lufbery’s death in 1918 had a deep emotional impact on the American flyers of the 94th Aero Squadron. Lufbery had been their commander and chief instructor. He had been with the first American volunteers since the days of the Escadrille Américaine, later renamed to the Escadrille Lafayette on the request of the US Government given its neutral stance in the Great War at the time. He was born of an American father, though raised in France, and he had been involved in aviation since 1911 when he had started as a mechanic for French flyer Marc Pourpe.

His leadership style too had a long lasting impact on American military aviation. His innovative tactics and overall approach to the aeroplanes of the time, learning the technical details of operations and studying the mechanical aspects of his planes, had a very long shadow. Even today, American pilot are masters of the technical details of their aircraft, a practice that has spread globally since the 1950s. By comparison, even into the 1960s, many European aviators laughed at any who got their hands dirty working on engines; all they needed to know was that when you pushed the throttle forward, you got more power.

Above all, Lufbery’s style of carefully maintaining and checking his aeroplanes and even polishing every bullet so that it would be less likely to jam his Lewis machine gun, left its mark. He is even reputed to have developed the military landing approach — the overhead break that involved a circling approach to land. That innovation solved the early problem of aviators landing in all directions at once on the field.

Ultimately, men of Raoul Lufbery’s character were rare, even among the company of heroes and early aviators who helped pioneer air combat during World War I. His passing came as a shock, but it was one that the American flyers soon learned to appreciate as his final lesson to them — air combat is a dangerous profession and death is never far away, even for the best.

A true hero, a remarkable leader, and an inspiration to all. He laid the ground work and helped define what it was to be a fighter pilot. In all that he was, and in how he carried himself, he became an icon for young men to follow. His death was not tragic, but offers another important lesson — that you must always stay vigilant and that the small things are still important, no matter how good you get as a pilot.

Such a humbling story told. To think, in the heat of battle… a seat belt??