Published February 18, 2015

by Thomas Van Hare

Did you ever wonder where the term, “The Right Stuff” came from? Most people would say that it was a product of the X-planes testing program out in the deserts of what would later be called Edwards AFB. However, the term as it pertains to aviation actually hails from earlier — in fact, far earlier.

In Tom Wolfe’s book, The Right Stuff, he makes the term famous. Wolfe, never one to write poorly, defines the term as follows:

“As to just what this ineffable quality was… well, it obviously involved bravery. But it was not bravery in the simple sense of being willing to risk your life… any fool could do that… No, the idea… seemed to be that a man should have the ability to go up in a hurtling piece of machinery and put his hide on the line and then have the moxie, the reflexes, the experience, the coolness, to pull back in the last yawning moment — and then to go up again the next day, and the next day, and every next day… There was… a seemingly infinite series of tests… a dizzy progression of steps and ledges, a ziggurat, a pyramid extraordinarily high and steep; and the idea was to prove at every foot of the way up that pyramid that you were one of the elected and anointed ones who had the right stuff and could move higher and higher and even — ultimately, God willing, one day — that you might be able to join that special few at the very top, that elite who had the capacity to bring tears to men’s eyes, the very Brotherhood of the Right Stuff itself.”

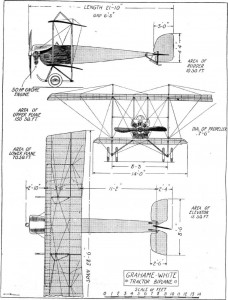

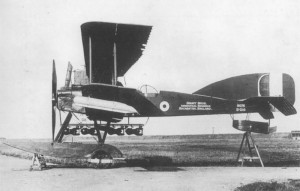

Popularizing the term may have been Tom Wolfe’s singular greatest achievement (besides writing such an excellent book), yet long before Wolfe was even born, another man would be termed as having “the right stuff” — and he was a new, hopeful aviator who purchased a veteran plane, a 50-h.p. Grahame-White tractor biplane that carried the moniker, “Lizzie”, at Hendon, near London. The year was 1914, and his intention was to teach himself to fly. His name was Mr. Charles Walter Graham, the son of Mr. C. K. Graham of 9, Kitson Road, Barnes, Southwest London, England.

Soon Mr. Charles W. Graham was out on the field taxiing around to get familiar with the handling of the biplane, no doubt intending to remain on the ground. “Lizzie”, however, had other ideas, as related in the November 27, 1914, issue of Flight, the newsletter of England’s Royal Aero Club:

It appears that a certain enthusiast has bought “Lizzie” with the object of teaching himself to fly, and that last Saturday was to be the dress rehearsal.

[…]

Starting off from the corner at the top of the ex-half-crown enclosure, a very neat straight roll was accomplished in the direction of No. 4 pylon, with the tail well up. After some prancing about on the bad ground out by No. 4, “Lizzie” was persuaded to turn back in to the wind, and before anybody had realised what was happening, she shot up in the air at an angle of about 450, the pilot switching on and off all the while. By some kind whim of fate, which the newspaper correspondents would probably have described as superhuman efforts, “Lizzie” just managed to avoid a tail slide, and proceeded on a comparatively even keel towards No. 1 pylon, whisking her tail from side to side in the friskiest of ways. The pilot evidently considered this the moment appropriate for coming down, a performance which he seemed likely to accomplish in quite good style, for he descended in a pretty good glide switching on and off, but unfortunately he spoilt it at the last moment by not flattening out sufficiently and by keeping his engine running all out after touching the ground. The result was that “Lizzie” took matters into her own hands and did a loop the wrong way round, finishing on her back, whilst the pilot was seen to drop out of his seat on to the top plane. He was up again in a second, however, waving his hands to show the anxious onlookers that he was none the worse for his “spill.” As a fact, the only damage done was a broken propeller and a bent shaft. It is to be hoped that “Lizzie” will soon be out of hospital again, since her owner is evidently made of the right stuff, and should, with a little patience, turn out a good pilot. Most initiates would certainly have made a worse job of it than he did.

On Christmas Day in 1914, Flight carried yet one more mention of “Lizzie” and Mr. C. W. Graham, who was attending a flight school at that point, having abandoned the idea of teaching himself:

At the Hall school several new machines will be put into commission shortly, among others a two-seater biplane that will have dual controls. This firm has been repairing “Lizzie,” after her little spill recently, and she is now almost ready to take the air again, and looks as well as ever. While awaiting her return from “hospital,” “Lizzie’s” owner is getting a little preliminary experience on the dual-control two-seater Caudron biplane of the Ruffy school, so as to get used to the handling before taking “Lizzie” out again.

Then surprisingly, the February 19, 1915, issue of Flight contained yet another reference to “the right stuff”, attributed to the very same pilot. The mention was made in the section entitled, “Eddies”, where news and items of interest were routinely and often informally, posted:

I hear that Mr. C. W. Graham, who, it will be remembered, made his debut into the flying world some time ago by a short but exciting flight on “Lizzy,” has now taken his ticket, and a very good one at that. The effects of that first flight, or rather of the landing with which it ended, necessitated some few weeks spent in hospital. That is to say, as far as “Lizzy” is concerned, as Mr. Graham himself came out of his little “spill” perfectly unhurt. Following a thorough overhaul at the Hall works, “Lizzy” was put in trim again, and after about two hours’ actual practice in the air, Mr. Graham obtained his brevet on Friday last. I am told by people who are daily watching pupils go through their tests that Mr. Graham’s was an exceptionally good one, his flying being extremely steady (and I should imagine that one has to have “hands” to fly “Lizzy”). The vol plané took the form of a half spiral, and he landed without the suspicion of a bump. It may be remembered that on the occasion of Mr. Graham’s first memorable flight, I ventured the prophecy that he would someday make a very good pilot, as he was evidently made of the right stuff, and it now seems that my prophecy is in a fair way to coming true.

Thus, it appears that the first aviator to have “the right stuff” was an Englishman, not an American test pilot after all!

By mid-February, as evidenced in the short quip in Flight on February 26, 1915, Mr. Graham was becoming quite adept at handling his new biplane:

Although “Lizzie” does not now indulge in looping, she has not yet by any means settled down to a steady trotting round the course at Hendon, but seems to take a delight in doing steeply banked right and left hand spirals, piloted by her new owner, Mr. Graham, who handles her remarkably well, considering that he only took his ticket a little over a week ago. Practically the only part of his piloting which is not yet quite all that it might be, is the landing, but this is improving, and with a little more practice he should fulfill the expectations of his instructors.

In March 1915, Mr. C. W. Graham was frequently seen aloft and had acquired a reputation for flying in all sorts of weather and winds — the March 12, 1915, issue of Flight contains this short quip about his flight the previous weekend:

OWING to the high wind, there was very little flying at Hendon on Saturday last, but the monotony was relieved in the morning by a short flight by Mr. Graham on “Lizzie,” and in the afternoon by the arrival of two machines from other aerodromes. Although only qualifying for his ticket recently, Mr. Graham is already acquiring considerable experience in rough weather flying — an experience which he never loses any opportunity of adding to.

Certainly, flying in various conditions is a focus of much modern flight training. Back in 1915, however, flight in high winds was rightfully considered hazardous. Whether Mr. Graham had acquired any skill at it or not is unclear, though he seemed determined to master flying in all sorts of conditions.

Just a month later, another mention of Mr. Graham pops up. In the April 9, 1915, edition of Flight, while describing a rather poor flying day at Hendon due to winds and weather, the reporter from Flight added this tidbit, which shows us that Mr. C. W. Graham was indeed a very fast learner and had quickly mastered the art of flying:

I began to picture an afternoon without a single flight. From casual remarks dropped by some of the visitors, I received the impression that the majority of these were fully aware of the dangers of airwork under the prevailing weather conditions, a fact which speaks well for the educational value of the meetings held at Hendon before the war. It was, therefore, more with a feeling of pleasant surprise than with one of disappointment at seeing no flights earlier in the afternoon, that the public greeted the appearance towards evening of Mr. Graham on “Lizzie.” His performance was truly a magnificent one, but personally I felt greatly relieved when he had landed safely, after giving a demonstration of his steep spirals, for the wind was tricky and treacherous. And, after all said and done, “Lizzie” has an engine of 50 h.p. only. However, all went well, and every credit is due to “Lizzie’s” owner for his plucky stunt, and for the masterly way in which he handled his machine.

[…]

Then came an exhibition flight by C. W. Graham on “‘Lizzie.” There was only one part of Mr. Graham’s work that did not over please us, and that was his steeply banked turns near the ground. Impressive, certainly, but –.

The writer obviously did not take well to Mr. Graham’s flying style in the high winds and bad weather of the day. In classically understated prose, leaving the hanging and unfinished sentence for the reader to imagine the fateful consequences that might follow, he conveyed his thoughts that Mr. Graham’s choice of flying was nothing short of reckless.

Likewise, the same April 9, 1915, issue of Flight carried a feature about the flying season opening at Hendon and described the conditions and Mr. Graham’s performance — the same flight — as follows:

On Friday the wind was in the neighbourhood of 30 m.p.h., so that flying was practically impossible. In spite of this, however, M. Osipenko came out on the 50 h.p. G.-W. school ‘bus and made a daring, although short, flight. Later on, C. W. Graham ascended on “Lizzie,” and put up a really magnificent performance ‘midst wind and rain. A downpour of rain then put the stop on further air work until about 6 p.m., when the weather cleared a bit, and H. Hawker arrived from Brooklands on a new Sopwith tractor biplane. Instead of alighting at once, he continued round and about over the aerodrome for some time before landing, just by way of formally completing an hour’s flight for Admiralty purposes.

As previously mentioned, Saturday turned out too bad for flying, whilst Sunday, although nice and fine, had a turn of stiff wind about, a change which brought in a good many visitors. The feature of this afternoon’s flying was C. W. Graham’s splendid exhibition, with his 50 h.p. G.-W. tractor biplane “Lizzie,” on which he put in various stunts, such as exceedingly sharp spirals and steep dives. To watch him it did not seem possible that it was only a short time ago that he taught himself to fly on the handy little tractor. Great things should naturally follow a pilot with such an air-touch.

So it would seem that Mr. Graham’s natural aptitude was indeed “the right stuff” after all. It certainly seems that among his peers back in the day he deserved the honor to be the first pilot to have Tom Wolfe’s “ineffable quality“.

Sadly, the story of Mr. C. W. Graham does not end well. The Great War was on and aviation was entering the fray in early 1915. Like many of his patriotic countrymen, Mr. C. W. Graham chose to ride to the sound of the guns. It should not surprise anyone that the April 23, 1915, edition of Flight carried this notation:

Royal Naval Air Service.

THE following announcement was made by the Admiralty on the 14th inst.:—

C. W. Graham, entered as Probationary Flight Sub-Lieutenant, for temporary service, with seniority of April 12th, and appointed to “President,” additional, for R.N.A.S.

There is some evidence that he attended “The Seaplane School, Windermere” where he learned on AVRO aeroplanes powered by Gnome 50 h.p. engines. After that, he deployed operationally with a squadron to Belgium, where he flew patrols along the coastal waters.

Just a year later, the September 14, 1916, edition of Flight carried the following notation, amidst an increasingly lengthening list of casualties from the Great War:

Roll of Honour.

THE Secretary of the Admiralty announces the following casualties:—

Accidentally Killed.

Flight-Lieut. C. W. Graham, D.S.O., R.N.

The exact circumstances of his death are not recorded, though one can imagine all sorts of scenarios, including that perhaps the claimed reckless streak in his flying style may have gotten the better of him — yet we cannot know.

Additionally, we note the appellation, “D.S.O.” after his name — no doubt there is a story there, but one that is mostly lost to us. All we have this, from the City of Coventry Roll of the Fallen:

Graham, C. W., D.S.O., Flight-Lieut., Royal Naval Air Service.

Born in 1894; Pupil, Triumph Cycle Company, Ltd. Accidentally killed off the coast of Belgium, 1916. Awarded the Distinguished Service Order in December, 1915, for sinking a German seaplane off the Belgian coast.

Likewise, the following record was found, offering confirmation and yet a bit more detail — this from February 24, 1916, in a special supplement to the London Gazette:

The King has been graciously pleased to approve of the appointment of the undermentioned officer to be Companion of the Distinguished Service Order: Flight Sub-Lieutenant CHARLES WALTER GRAHAM, R.N. For his services on December 14th, 1915, when, with Flight Sub-Lieutenant Ince as observer and gunner, he attacked and destroyed a German seaplane off the Belgian coast.

Finally, at the end of 1915, the Admiralty published an official announcement regarding the victory scored by Flight Sub-Lieutenants Arthur Ince and Charles Graham, which offers yet a little more detail of the fateful events of that day:

Admiralty, Dec. 14th.

“Flight Sub-Lieutenant Graham, R.N.A.S., in an aeroplane with Flight Sub-Lieutenant Ince, R.N.A.S., as observer, whilst on patrol off the Belgian coast at about 3.15 this afternoon, sighted a large German seaplane and gave chase. After a severe engagement the German machine was hit and fell. Before reaching the water it burst into flames and at the moment of striking exploded. No trace of the pilot, passenger, or machine could be found. Flight Sub-Lieutenant Graham’s machine was severely damaged by machine gun fire and fell into the sea, but both officers were picked up and safely landed.”

A joint citation published in Gazette Despatches on December 24, for Flight Sub-Lieutenants Charles W. Graham and Arthur S. Ince read (and confirmed that it was Ince, serving as Graham’s gunner in the two-seat Nieuport 10 fighter, who shot down the Germany seaplane):

“Whilst on patrol on 14th December 1915 sighted an enemy seaplane at some distance. He immediately closed and manoeuvred into position astern and below the seaplane which was by this time endeavouring to escape towards Ostend. Flight Sub-Lieut Ince opened fire with the machine gun and after a bit of manoeuvring so as to bring the gun to bear again the enemy machine dived vertically into the water catching fire on the way down.”

On December 29, 1915, Flight Sub-Lieut. Graham was promoted to the rank of Flight-Lieutenant. Subsequently, on February 8, 1916, Flight-Lieut. Graham was listed by the Admiralty as “seriously injured”, though the circumstances of that remain mysterious. Whether Flight-Lieut. Graham saw more action or not is unclear from those records, as the one mention that follows in the June 1, 1916, issue of Flight, reads simply, “Lieutenant ‘Lizzie’ Graham also paid us a visit, looking very fit in spite of the nasty strafing he received recently.” The “strafing” described could be a reference to his tangle with the German seaplane earlier in the year.

Modern history books shed only a scant bit more light on the topic, though they do give an indication of the circumstances of his accidental death and some details of the types of planes he flew and what assignments he had. This is from the North Weald Airfield Museum Archives, in their publication, “West Essex Aviation Crashes and Mishaps”:

July 31, 1915 Charles W. Graham was flying a Caudron G.III, 3275, on 31 July 1915 from Chingford when he crashed and the aircraft was completely wrecked. Graham who gained a DSO during his short career was soon in action. On 2 October 1915 he flew Nieuport 10, 3184, with 3 Squadron on a hostile aircraft patrol from St Pol. On 14 December 1915 he was in action flying Nieuport 10, 3971, when he shot down a large German seaplane into the sea in flames NE of Le Panne but was then forced to land in the sea, the aircraft overturned and sank. Graham and his crewman Ince were rescued by the Balmoral Castle. He was killed on 8 September 1916 when the Short 184 seaplane he was flying on patrol from Yarmouth stalled from 200 ft and dived into the sea and his bombs exploded.

Quoting from ‘Diary of a North Sea Air Station’ by Snowden Gamble, ‘He had only recently joined from Dunkerque air station, and on that morning (the 8th) he had just left the water in a Short seaplane, but turned down wind before his machine had apparently attained full flying speed, with the result that his machine stalled and dived into the sea from about 200 ft. The bombs exploded and Graham was killed instantly, but his body was not recovered for another fortnight.’

It was a sad end for the first pilot to have “the right stuff”. Flight-Lieut. Graham’s death in the autumn of 1916 was rightfully declared accidental and therefore not the result of direct enemy action. Nonetheless, one should always bear in mind that the aeroplanes of the day were being developed and pressed into service at rapid rates. That practice led to many more accidents than might have taken place at the more polished, slower pace of civilian life.

Rest in Peace, Flight-Lieut. C. W. Graham, D.S.O., Royal Navy — and thank you for your service.

We have but one photo of Flight-Lieut. C. W. Graham, D.S.O., Royal Navy, as above, though it is not beyond imagining that one of the enterprising readers of Historic Wings will post additional images in the coming weeks or months, such is the reach of our magazine. Thank you all for your patronage.

Does anyone have more information or photographs to share regarding Flight-Lieut. C. W. Graham, D.S.O., R.N.?

See this from Wikipedia:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/charles-walter-graham-18931916-dso-rnas-40717

This is an artist’s portrait of C. W. Graham.

There are also two pages in the “Find A Grave” collection, showing the location of C. W. Graham’s grave:

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Graham&GSfn=Charles&GSmn=Walter&GSbyrel=all&GSdy=1916&GSdyrel=in&GSob=n&GRid=25797714&df=all&

and

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Graham&GSfn=Charles&GSmn=Walter&GSbyrel=all&GSdy=1916&GSdyrel=in&GSob=n&GRid=58993685&df=all&

Great article and welcome back. I have missed your stories.